Falconry Month at Birds and Booze:

I’ve decided to dedicate this month of March 2019 to wines and beers related to the history of falconry – or hawking – for no other reason than that I’ve recently acquired several bottles adorned with mostly medieval European iconography relating to this “sport of kings”. While the hunting of game with trained birds of prey can be a controversial topic among birders, falconry was a valuable early source of information on birds, and its history, culture, and imagery continue to fascinate bird lovers, as we shall see.

Few hobbies place such value on the written knowledge contained in books as does birding. Birders cherish and hoard books above all other trappings of the pastime, and rather than relegating these tomes to the home library or study, they’re routinely carried out-of-doors as constant and dog-eared companions in field and forest. Books about birds are a wealth of written and pictorial information to birders, and an exalted few have become watersheds in the history of ornithological study: Ornithologiae by Francis Willughby, Birds of America by John James Audubon, and Guide to the Birds by Roger Tory Peterson, to name just a few of the most legendary.

But predating these and indeed almost all other ornithological texts in history is a medieval book on falconry: De arte venandi cum avibus (“On the art of hunting with birds”), a treatise on the sport written by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen. This book is no mere dabbling by a royal dilettante either: De arte venandi cum avibus is a serious and comprehensive study not only of the birds of prey employed in falconry, but a logically structured catalog of Frederick’s own keen and sometimes radical observations of all the birds he knew.

There had been works on falconry before Frederick’s time: treatises on falconry date back to the 10th century in Europe, and King Harold of England (of Battle of Hastings fame) reputedly owned the largest collection of volumes devoted to the subject in all of Europe. And sometime before Frederick completed his own work, he acquired a five-volume treatise on falconry in Arabic by a writer known to the Europeans as Moamyn – perhaps while in Palestine during the Sixth Crusade in 1228 and 1229 – and had it translated into Latin as De scientia venandi per aves by a Syriac named Theodore of Antioch, who was employed at the emperor’s court in Palermo.

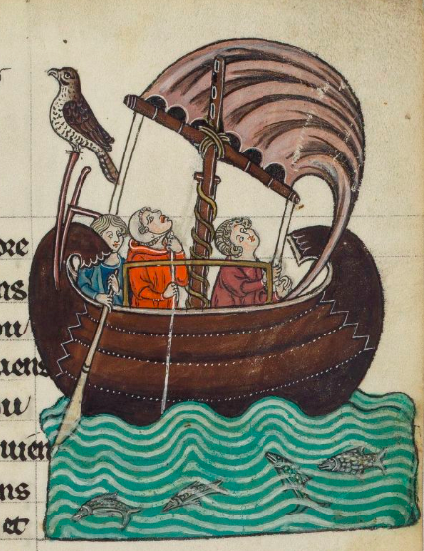

Possibly the first documentation of a ship-assisted bird in history, undoubtedly sailing off the edge of the world.

So, in writing his own falconry treatise, Frederick drew on all sources of knowledge on birds available to him at the time, including the Aristotelian tradition inherited from antiquity, medieval bestiaries imbued with preordained Christian morality and symbolism rather than the careful observation of natural phenomena, as well as translations of later, more enlightened works by Arab falconers and scholars. But in many cases, Frederick found that the claims of these vaunted but unthinking sources stood in contrast with his own experiences as both a falconer and keen observer of birds. In De arte venandi cum avibus, he corrected and supplemented this comprehensive survey of the existing literature with his own empirical observations and logical inductions – and methodically organized these natural histories in a work that is startlingly ahead of its time.

Could this be the first “accipiter sp.” report in history?

For instance, Frederick rejected centuries-old folk wisdom that claimed that Barnacle Geese (Branta leucopsis) – a species with a seasonal occurrence in Europe – were born not of eggs laid by breeding geese but were spontaneously incarnated from driftwood afloat at sea. Of course, this fanciful story had been devised to explain the absence of nests in Europe by this Arctic breeder, but Frederick dismissed it as nonsense. Instead, he surmised that Barnacle Geese merely breed in far-off lands and return south in winter – perhaps one of the earliest explanations of migration in history.

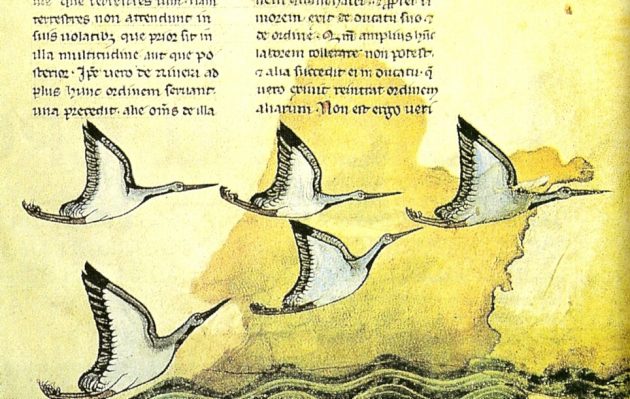

Medieval migration: “The swallow may fly south with the sun or the house martin or the plover may seek warmer climes in winter, yet these are not strangers to our land?”

Some of Frederick’s observations were more mundane, but no less astute and revolutionary for his time. He noted that raptor plumages sometimes varied according to the age and sex of the bird (he really was a birder!), and also theorized that birds breed in the spring as the warmth of summer offers the best conditions for the rearing of offspring. And whenever ancient texts or folklore failed to provide a satisfactory explanation, Frederick conducted what would now be recognized as scientific experiments to discover the answer himself. He blindfolded vultures to determine whether they could locate food by sense of smell, and also sought to determine if chicken eggs would hatch by the warmth of the sun alone, rather than from being incubated by a hen. It was probably for Frederick’s more worldly exploits – among them the establishment of the University of Naples, outlawing the superstitious trial by ordeal, and waging war against no fewer than four popes – that a contemporary chronicler dubbed the emperor stupor mundi (“the astonishment of the world”). But to we latter-day birders and ornithologists, Frederick’s greatest accomplishment was his rejection of the prevailing dogmatic views on the natural history of birds, which he replaced with his own carefully recorded observations. At the time, this amounted to heresy and resulted in the suppression of his writings by religious authorities for centuries (though his antipapal campaigns probably had something to do with that, as well).

Frederick completed De arte venandi cum avibus toward the end of his extraordinary life, sometime before 1248. The original six-volume manuscript was sumptuously decorated in gold and silver but was lost at the Battle of Parma in 1248, when the emperor’s siege camp was destroyed by factions supporting Pope Innocent IV (not surprisingly, Frederick was away hunting – undoubtedly with hawks or falcons – at the time of the attack). After the death of Frederick in 1250, his illegitimate son and heir, Manfred, commissioned a new edition, which was completed during his reign as the last Hohenstaufen King of Sicily from 1258 to 1266.

This copy is by far the most famous version of the seven extant medieval copies of De arte venandi cum avibus. Like the others, it is a torso of Frederick’s original work, in its case ending near the end of what had been the second of six volumes. The manuscript, comprising 111 folios, now resides in the Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana. Owing to its provenance in the intensely intellectual, artistic, and scholastic court of 13th-century Palermo, this illuminated codex is one of the most remarkable repositories of falconry images and – by extension – the medieval iconography of birds in general.

The Vatican edition of De arte venandi cum avibus contains over 660 outstanding manuscript illuminations depicting every aspect of the practice of falconry in exquisite detail – and at least 80 different species of birds. One of these images is a depiction of four dark falcons with speckled breasts perched on a rail. Their hefty bearing and prominent beaks, as well as the dark mustachial stripe on each bird, suggests that they may be Gyrfalcons (Falco rusticolus), a favorite species of medieval royal falconers. Whatever they may be, the image makes a handsome label for this week’s wine, the 2015 Siir from San Martino, a vineyard in the Aglianico del Vulture region of Basilicata in Italy.

There are letters from Frederick II requesting Gyrfalcons from Greenland, a place then only known to Europeans for fewer than three centuries.

To my knowledge, the chronicles don’t record the wine preferences of Frederick II. But there’s a good chance the medieval emperor was drinking a good deal of Aglianico, a venerable grape variety first brought to Frederick’s southern Italian homeland by Greek colonists, and later beloved by the ancient Romans. The poet Horace sang its praises, and according to legend, Hannibal rewarded his armies with Vulture wines after a victory over Rome. Even our pioneering ornithologist Frederick II is said to have promoted the cultivation of Aglianico vines within his realm in Basilicata, a region he visited often for hunting. With such a pedigree, it comes as no surprise that the French winemaker and professor of oenology at the University of Bordeaux, Denis Dubourdieu, stated that “Aglianico is probably the grape with the longest consumer history of all.”

Aglianico vines are still grown in southern Italy today, particularly in area around Mount Vulture, an extinct volcano in Basilicata. The varietal thrives in the volcanic soils that dominate in the south of Italy, and the grape is much used in producing Aglianico del Vulture, a red wine that is the only Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG) wine from Basilicata.

Although not particularly well known, Aglianico del Vulture wines are generally regarded as excellent, with great potential for aging owing to their lively acidity and tannins. At three years old, the 2015 Siir from San Martino is admittedly a bit fresh, but even in its youth, the intention of winemaker Lorenzo Piccin comes through beautifully in this wine. This deep red is imbued with fruity but dry aromas of black cherry and blackberry, supported by floral hints of violet, spicy licorice, and leather. The wine is strongly tannic, with a slight bitterness that should mellow after a few more years, but still retaining enough acidity to counter its rich, plummy flavors.

This Aglianio del Vulture is a wine that should improve a good deal over time. And with its origins in the ancient, volcanic earth at the heart of Frederick’s former realm in the south of Italy, and being made from one of the oldest grapes known to winemaking, it makes a fitting glass to enjoy while poring over images from De arte venandi cum avibus, the beautiful but unlikely ancestor of all the field guides sitting in your birding library.

Frederick II, author of De arte venandi cum avibus, posing here with one of his hunting companions (hooded).

Good birding and happy drinking!

San Martino Siir (2015) – Aglianico del Vulture DOC

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Four out of five feathers (Excellent)

Leave a Comment