Drinking is an act of risk and vulnerability, though it’s such an everyday part of our existence that no one thinks of it that way. There’s always a chance that we could ingest something bad for us, something that might even kill us – a peril we face anytime we swallow anything, in fact. But drinking is essential for life, so despite the danger, we continue to imbibe.

Nowhere is this contradiction between pleasure and danger more evident than in the intake of fermented beverages. Alcohol itself is a poison, produced by a sort of controlled spoilage, but fermented beverages often contain bitter and sour elements as well, potent and immediately detectable flavors that trigger urgent warnings of dangerous toxins in the oldest, most antediluvian corners of our brains. While this response evolved as an important safeguard against eating poisonous plants, our gustatory defense still errs on the side of caution, allowing the ingestion of perfectly benign food and drink to overload the panicked brain with false alarms. While some people never overcome this vestigial aversion to sour and bitter sensations, this innate prejudice can be overturned with experience, becoming acquired tastes we learn to enjoy just as much as the more dependable, uncomplicated pleasures of sweetness, salt, and fat.

Thanks to the relatively recent marvels of pasteurization and other modern production methods, the notion of a sour beer is an oxymoronic one for many, and an unappealing prospect for others, but beer has been turning sour throughout its history, even becoming a preferred quality in some styles. It was only through trial and error over the centuries that brewers eventually learned how to prevent or postpone this souring with natural preservatives, or to let it run wild when desired, resulting in the impressive range of tastes exhibited by beer today, running from the puckeringly tart to the sweet and syrupy.

For just as long, brewers have been tempering the sweetness of malted barley with a requisite dosage of bitterness. In the last several hundred years, this service has been performed by hops, but before their widespread adoption in medieval Europe, brewers relied on a compendium of botanical agents to bitter their beers – some of which contained psychoactive or mildly toxic substances. Taken individually, sourness and bitterness can be essential flavor components in beer, but throughout history, they’ve wisely kept apart. Even our language treats these flavors with suspicion: consider “bitter regret” or a “sour look.” Long before the science and physiology of taste were formally understood, brewers knew to avoid jarring combinations of sour and bitter flavors that signal poisons to our brains. In the world of brewing, some beers could be sour, and others bitter, but one at a time, only, please. Tart is tart and hoppy is hoppy and never the twain shall meet.

Well, until now. After four decades of establishing bitter hoppiness as the hallmark of their brand of craft brewing, American brewers have turned their attention to other brash flavors, diving headlong into sour brewing of late. In an ever-changing industry obsessed with trends, “sour is the new hoppy” has been the new maxim. But it didn’t take long for some adventurous brewers to begin wedding these potentially clashing flavors together in a single beer, grappling with all the flavor problems this troubled arrangement entails. The idea has caught on, putting a notable increase of sour IPAs, dry-hopped sours, and other “hoppy sours” on the market in last year or so.

What makes these latter-day “hoppy sours” work is taming the bitterness with later hop additions that extract all the bright, tropical fruit and citrus aromas and flavors of novel hop varieties that pair so naturally with a lemony acidity, without adding the resinous, mouth-numbing bitterness that characterizes West Coast IPAs. So, while hoppy sours retain some bitterness, overcoming our primal fear of this flavor combination requires a delicate touch in the brewery, but brewers seem to be working out the details quickly enough. Hoppy sours are still in their infancy, and they may take some getting used to, but at their best, they can be downright delicious and refreshing.

By most reckonings, the Northern Hemisphere is in the middle of the so-called dog days of summer. Beer, like all food and drink, is best enjoyed by following the seasons. As an emerging style, hoppy sour beers have yet to find their proper place on the calendar, but to my mind, a tart and refreshing, slightly bitter, alcoholic tipple – one that ticks all those poison warning boxes buried deep within our lizard brains – is just the thing for these long, languorous August days. The dog days were thought by the ancients to be vexed by heat, storms, bad luck, pestilence, and madness – the perfect season for the perverse pleasures of playing tricks on the mind.

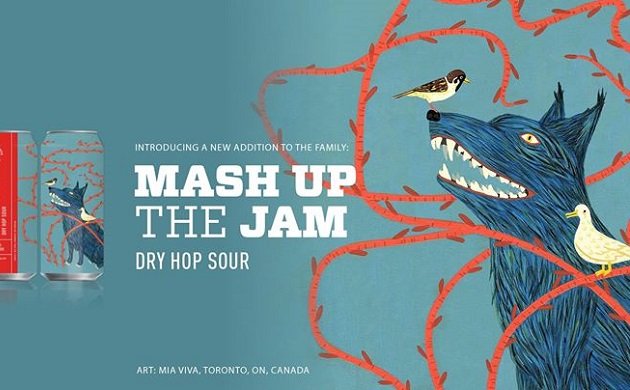

In that deviant spirit, this week’s beer is Mash Up the Jam, a new dry-hopped sour beer by Collective Arts Brewing of Hamilton, Ontario. The name suggests a reckless, world-turned-upside-down approach, and the brewery admits the beer was an attempt to bridge a longstanding divide by appeasing hopheads and sour beer enthusiasts alike. But the vivid can artwork by Toronto illustrator Mia Viva also suggests that Collective Arts is at peace with this disruption of the natural order, depicting an improbable scene of a suitably dumbstruck white domestic duck sitting alongside a menacing wolf, with a fearless little songbird unwisely perched on the canine’s nose. Whether this is a cameo by three-quarters of the animal cast of Sergei Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf (only the cat is missing – kept indoors, I presume, by a responsible owner) or perhaps a send-up of Edward Hicks’s messianic vision of The Peaceable Kingdom is unclear, but the songbird appears to be, rather implausibly, a Eurasian Tree Sparrow (Passer montanus). I suspect this will be the first and last time we’ll see a beer featuring this species, an introduced Old-World songbird best known in North America from its St. Louis, Missouri population. That is, unless some St. Louis brewery decides to put the city’s best-known invasive on a can of beer. (Your move, Budweiser.)

If you can advertise beer with Clydesdale horses, bull terriers, and bullfrogs, I don’t see why you can’t use a Eurasian Tree Sparrow. I’m glad that Collective Arts Brewing agrees.

As promised, Mash Up the Jam offers up a blend of sour and bitter flavors guaranteed to elicit the expected “cry-wolf” response (maybe that’s what it’s doing there on the can) from our overly-cautious taste buds, but fearless drinkers will carry on with dogged persistence despite the subconscious warnings of poison. The beer is hazy and straw-colored, with a dull and pale greenish tinge undoubtedly left behind by the copious amounts of Nelson Sauvin and Vic Secret hop that flavored it. Mash Up the Jam is pungent with lime and candied lemon aromas, going through a slightly grassiness that gives way to sweet, fruity notes of gooseberry, mango, and pineapple. A yuzu sourness puckers the palate immediately, softening with overtones of white wine and chilled limoncello, before ending on a tart cranberry note. The most noticeable hop bitterness comes through in the citrus rind finish, while a pleasantly husky malt sweetness emerges – somewhat surprisingly – at the very end.

Mash Up the Jam may deny us the chance to pick our poison – you’ll get both bitter and sour whether you like it or not – but it’s a worthy experiment combining two assertive flavors at the forefront of craft brewing. And, if we believe the stories of people throughout history who’ve self-administered poison in minute doses to build up their immunity over time, from Mithridates to Rasputin, there may very well be some value in getting used to these flavors. So drink up.

Good birding and happy drinking!

Collective Arts Brewing: Mash Up the Jam

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Three out of five feathers (Good).

Leave a Comment