I am something of an aficionado of National Wildlife Refuges. On this site, I have attempted to list the top 25 NWRs for birding, explained how to learn more about a particular NWR, lauded the importance of Federal Duck Stamps, and generally extolled the importance of the system to birds and birders. I am also a dutiful eBirder.

But I somehow missed the introduction of some cool new features specifically for eBirding NWRs.

The new features are called “Explore a National Wildlife Refuge,” and they can be found in the “explore” tab under the “explore a region” sub-tab. The essence of the new features is that they allow users to more easily and efficiently analyze data for NWRs. They allow casual users of eBird (e.g., most birders) to delve more deeply into the data for a local or favorite refuge.

This is an excellent development: the National Wildlife Refuge System is likely the most important avian conservation system in the United States and separately providing NWR eBird data can only reinforce that important fact and make it more widely known to birders.

For anyone visiting a refuge with multiple hotspots (e.g., most refuges), the new functionality allows one to easily create a bar chart for the entire refuge. There is no longer a need to manually include each hotspot that is specifically identified as being located within a refuge. Nor is one required to determine which hotspots are located within a NWR. And an eBird user can readily see the total number of species observed, the number of observations, the top birders by species and number of checklists, etc. It is easy to pull up recent checklist and other useful data. All of the previous functionality still exists, so these new features just make everything easier.

I assume these features were developed by overlaying maps of NWRs over all locations. I further assume that all observations — not just hotspots — within the boundary of an NWR are included in the resulting data for a particular refuge. That would allow easier analysis of all of relevant data, including submissions for both hotspots and personal locations.

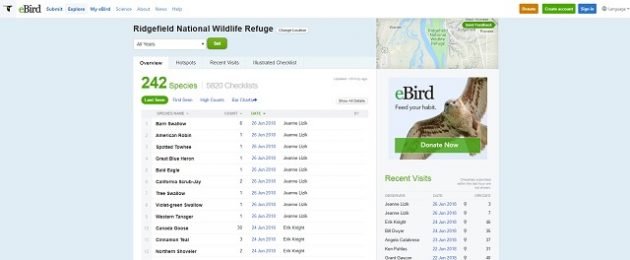

As an example, we can use a refuge near me: Ridgefield NWR in Washington. On the overview page, eBird reports that there have been 242 species observed and nearly 6,000 checklists submitted. There are tabs for the six hotspots on the refuge, recent visits to the refuge, and an illustrated checklist for the refuge. There is a tab for creating a bar chart as well. eBird tells me that I am the No. 25 eBirder at the refuge as to species (133) and No. 9 as to checklists (90). Although the underlying data has long been available, this ease of access is new and useful.

These new features are great, but they also highlight some shortcomings and suggest some areas for improvement.

For example, some hotspots within the boundaries of a National Wildlife Refuge are not consistently identified as such. Many NWRs contain several hotspots and the practice is to name these sublocations by reference to the well-known general location separated by dashes (e.g., “Santa Ana NWR–Pintail Lakes Trail”). This hotspot naming practice is set forth here (“Sub-locations should always follow the primary location separated by a double dash”).

There are a remarkable 44 sub-location hotspots within Malheur NWR in Oregon. They include: “Malheur NWR–Headquarters” and “Malheur NWR–Benson Pond.” But there is also “OO Ranch Road” and others that are not labeled as part of Malheur NWR. This observation might appear be pedantic or immaterial, but eBird wants the most accurate location and hotspots without the proper name are probably less likely to be chosen, even if more accurate, especially by visiting birders using eBird mobile who likely do not know the local location names. And, of course, there is value in eBird following the naming conventions that are articulated by eBird. A hotspot within a NWR should be identified as within the NWR. (Update: The eBird hotspot coordinator for Oregon emailed me saying the hotspots in Malheur NWR have been modified.)

As another example of confusing naming, the hotspots for Ridgefield NWR discussed above include both a “Ridgefield NWR” and a “Ridgefield Wildlife Refuge.” For those entering checklists on eBird mobile, that is perplexing. Even with the hotspot map, this implied distinction is difficult to ascertain, likely because it is a simply a mistake. (Also puzzling: The hotspot called “Ridgefield NWR–Entrance Road Redwoods” is evidently not within the refuge, as it does not appear in the list of its hotspots.)

This new functionality seems like an excellent opportunity for eBird to clean up the hotspot names to comply with its own conventions and to revisit the hotspots themselves to reduce duplication and confusion.

Additionally, the search bar for the “Explore a National Wildlife Refuge” page states “Enter a National Wildlife Refuge or other USFWS location…” This suggest that the non-NWR units of the National Wildlife Refuge System can be accessed. But that does not appear to be accurate.

For example, Waterfowl Production Areas (WPAs) are little-known but critically-important units of the Refuge System in the Prairie Pothole Region of the United States. WPAs support huge populations of waterfowl and other birds. Funk WPA in Nebraska is one of the larger WPAs (approximately 1,900 acres) and it is an eBird hotspot. Yet typing “Funk” in the search bar returns only a “No Matches” message. The same is true for Townsend WPA, home of the eBird hotspot Prairie Wetlands Learning Center (below) in Minnesota.

It would be great to add all units of the Refuge System, though it is obviously easier to add approximately 550 NWRs than it is to add more than 30,000 WPAs, some of which are just a handful of acres.

Naturally, when eBird provides increased functionality, birders will inevitably want more. For example, since eBird can now separately collect and analyze all my checklists within the National Wildlife Refuge System, perhaps eBird could provide my life list for the entire system, as it does for the ABA Area or AOU Area. I have wondered what my NWR life list is but it is not easy to calculate. (At least it is not easy for me. If it is, please let me know in the comments.)

All in all, these new features are an excellent addition to eBird and I applaud this increased attention to eBirding NWRs.

# # #

Birders who bird on National Wildlife Refuges should note that the 2018-2019 Federal Duck Stamp is now available (as of June 29, 2018). Conservation minded birders should consider buying a stamp every year, as it is one of the easiest and most effective ways to support the Refuge System. Stamps can be purchased online from the USPS, at many refuges, and via the American Birding Association. Duck Stamps have contributed enormously the the best NWRs for birding.

# # #

Photo of Prairie Wetlands Learning Center by USFWS Midwest Region.

Thanks for posting this. I hadn’t noticed that feature even though I use the hotspot explorer quite regularly.

With regard to the hotspot names, it might help if eBird allowed users to flag problems like inconsistent terminology, misspelled names, or hotspots pinned in the wrong place, similar to the way that users can currently flag misidentified photos.