I’m publishing this article later than usual but it’s the subjects themselves that are responsible. Since the 1970s I have been monitoring a wintering roost of Crag Martins (Ptyonoprogne rupestris) at Gorham’s and Vanguard Caves, off the east side of Gibraltar. The average wintering population is around 2,000-3,000 birds but numbers have varied significantly between years and even within the winter itself. A couple of years ago, particularly cold conditions further north seem to have been the cause of an unprecedented influx, when we had up to 27,000 birds at the roost!

When going up to count the entry of birds tonight, I wondered what results we would get. Last week there were 800 birds at the roost, about right for the time of year, with more due to come. With the bad weather in parts of Spain last week, especially along the east coast, I wondered if that might have had an effect by speeding the arrival of Crag Martins. Recoveries of birds we have ringed at the caves have shown us that these birds come from as far as the Italian Alps and an east coast route for them seems logical, supported by a recovery in Castellón.

Well, from the outset of the count, it was clear that it was going to be big. Crag Martins started to arrive an hour-and-a-half before sunset, soon swarming over the vegetated slopes above the roost as they caught the last insects of the day. In the end we counted just over 5,500 birds! Last year was a poor year with under 3,000 birds on average, so it’s great to see numbers reaching above-average figures already, with more birds due to arrive during November.

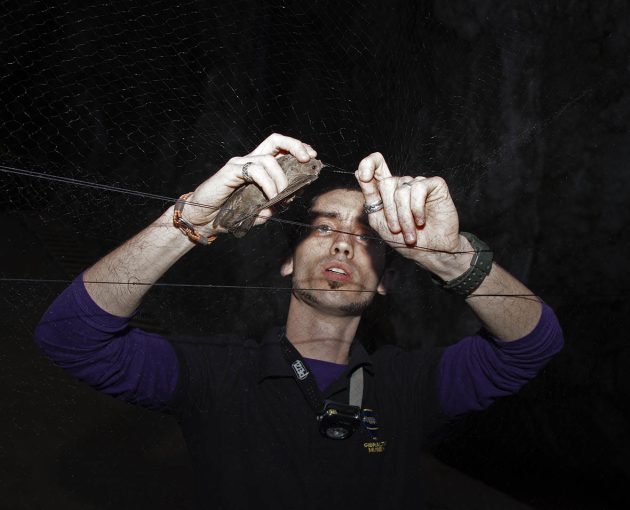

We have been studying the roost for some years now with some very interesting and exciting results. It turns out that individual birds occupy particular caves within the complex of caves. They are faithful to the cave, returning each night throughout the winter and even from one winter to the next. There is almost no intermixing of birds between the caves, which are very close to each other.

Gorham’s Cave appears to be the best cave, perhaps because of particular microclimatic conditions. The birds here are always in better condition, with higher body mass than those in the other caves. Their survival rates are also higher. Many of these birds are adults, experienced birds at selecting the best ledges inside the caves.

All this is highly important for birds that rely exclusively on aerial insects for food. During bad weather the birds will stay at the roost and won’t feed. They rely on body fat to see them through these lean periods. If these are long, many birds will perish. So, the success of the Crag Martin, the only aerial insectivore capable of surviving the European winter, is to behave like a migratory bird in transit. During warm and sunny spells feed on as many insects as you can and lay down fat. Then use up the fat when it becomes impossible to catch insects.

These “brown swallows” were reported by the Reverend John White, stationed at Gibraltar, to his brother Gilbert White of Selborne in 1771. He saw them precisely entering the roost which I have described! White’s observations started a thinking process that suggested that swallows migrated rather than bury themselves in the mud in ponds for the winter.

There is one further twist to my story. When we started excavating in these caves, sites that had been occupied by Neanderthals 100,000 years ago, we found the remains of Crag Martins! Yes, here was evidence of a roost that had been active for tens of thousands of years. When I see the birds at the roost, I cannot help but think that I am seeing what a Neanderthal once saw. Now that’s heritage!

Wow! What a fascinating history these birds have. The photographs are stunning. I especially liked the one of the cave mouth at sunrise.

Fascinating!

Wonderful. I love reading your articles as they are simple whilst describing complex discoveries, and always transmitting joy of science. Thank you.