Last year no fewer than 18 million tourists from Britain visited Spain – it’s our favourite holiday destination. However, of that 18 million, nearly all visited the Mediterranean coast. Few British people have ever heard of Extremadura, and even fewer would have visited this comunidad autónoma (autonomous community) that covers over 16,000 square miles to the west of Madrid. Extremadura is an area of huge skies and sprawling steppe – there’s nowhere else in Europe quite like it. Its special habitats harbour special birds, and that’s why it’s a favoured destination for birdwatchers.

The Cáceres Plains, with the snow-covered Sierra Gredos in the background

Finding bustards in Extremadura has always been something of a challenge (it’s much easier in the area around La Moraña and Villafáfila in Castilla y León). There’s a lot of suitable habitat to look for them in, and that’s part of the problem. Thirty years ago the Belén road out of Trujillo was a hot spot for bustards, both Great and Little, but it failed to reveal any this time. But we did eventually find Great Bustards on three occasions, with the best sightings on the rolling cereal fields on the Cáceres Plains. Twenty years ago there were reckoned to be 2000 Great Bustards here: I’ve no idea how many there are today, but I suspect that the population is now rather lower.

Bad news for steppe birds: a solar farm under construction

Despite their size – a Great Bustard cock is the size of a turkey – these birds can be difficult to spot, as their beautiful cryptic plumage blends perfectly with their surroundings. The birds we found we watched at considerable range, but they are such an iconic bird of the steppes that every sighting was exciting, and especially so for my companions who had never seen them before. Incidentally, this is not the place to try and photograph them, as they tend to be both wary and generally unapproachable. (For superb pictures of Great Bustards, see Clive Finlayson’s recent post https://www.10000birds.com/the-time-of-the-great-bustard.htm).

Great Bustards – challenging to see, and even harder to photograph

Though we may have enjoyed sustained, if distant, views of Great Bustards, we failed to find the Great’s smaller cousin, the Little Bustard. This was worrying, for I’ve never failed to find them before. One reason may have been due to the fact that the males had yet (at the end of March) to start their spring display, but there’s no doubt that the main explanation is because this species has suffered a huge decline. I’ve failed to find up-to-date figures, but from 1998-2017, numbers in Spain plummeted by 76.2%.

Though we failed on Little Bustards, there was some compensation with sandgrouse – we saw both species that occur here, the Black-bellied and the Pin-tailed. Our most notable sighting was of the latter, when we found a flock (or, rather, a number of small flocks, flying together) that numbered over 100 birds. We heard them before we saw them, for their beautiful flight-call is both far-carrying and distinctive. As the flock flew over I had the dilemma of whether to try and photograph them or just enjoy them. I tried the former, but as you will see from my photograph below, not with notable success.

While we may have struggled to find bustards and sandgrouse, larks were not a problem. The most distinctive lark here is the Calandra, a big lark that is distinctive with its black underwings and slow, flapping display flight. Their rich song is the wonderfully evocative sound of the steppe, together with the jangling song of the Corn Bunting. Thekla’s lark (the other common lark) is not as musical as the Calandra, but its simpler song is still pleasing to the ear.

Calandra Larks – big and distinctive

Griffon Vulture – a common sight throughout Extremadura

Griffons are less impressive on the ground than in the air

Raptors are an Extremadura speciality, and we saw lots of them. Griffon Vultures are abundant, and it’s rare to look up into the sky and not see several of them soaring overhead, often in company with Black Vultures. The latter is slightly the larger of the two, and is easily identified by its distinctive jizz, with drooping hands (the tips of the primaries). Extremadura has the biggest colonies of Black Vultures of anywhere in the world.

Here in Britain the Montagu’s Harrier has always been a very rare bird, and in recent years there have been no confirmed breeding records. It’s a bird we saw several times, with rather more cocks than hens. This was probably because the cocks return from their wintering grounds in Africa earlier than the females.

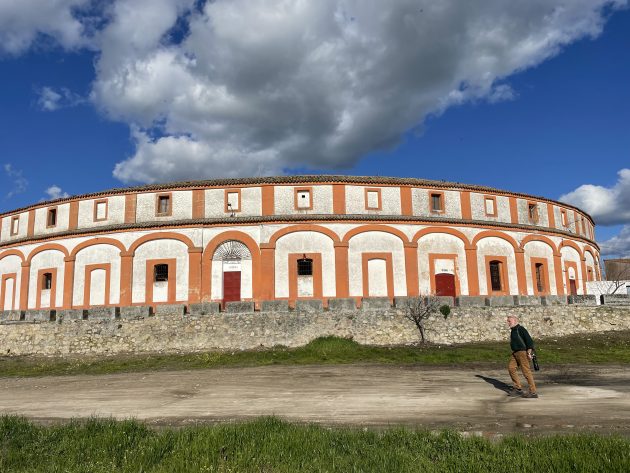

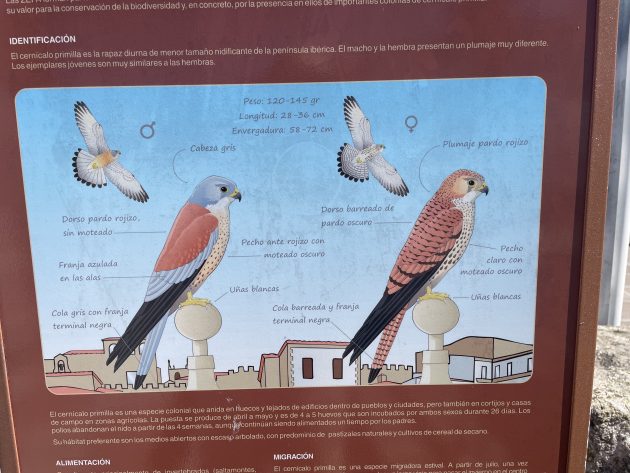

The plaza de toros in Trujillo: it was built in 1848. No longer used for staging bull fights, it supports an important colony of Lesser Kestrels (below)

Lesser Kestrels (above) are another Extremadura special, and we enjoyed great views of these delightful little falcons on many occasions, most notably by the the plaza de toros (bullring) in Trujillo, where they nest. Thanks to work by organisations like SEO, local people are now aware of the importance of the Lesser Kestrel colonies in their towns. The information board below was in the historical town of Alburquerque, close to the Portuguese border.

(Next week I will consider some of the other avian delights of this wonderfully bird-rich part of Spain.)

Leave a Comment