About six-and-a-half years ago I had the privilege of watching a young Waved Albatross on the Galapagos island of Española learning how to fly. The sight of the large bird, so awkward on the ground, trying to launch itself with the coaching of an indefatigable parent, was funny, charming, and amazing in its uniqueness. It’s not often that we have the opportunity to glimpse the home life of albatrosses, nor of any seabird species. Albatrosses, shearwaters, petrels, storm-petrels, fulmars, skuas, alcids, frigatebirds, gannets, boobies, tropicbirds—these are birds of legend that spend most of their lives at sea—the deep sea, not our familiar harbors and beaches—and even when they come to land to breed, it is often in places that are inaccessible, not to mention rocky, windy, and freezing cold.

Until recently, there has been a black hole in the ornithological body of knowledge about seabirds. Think about it–how do you document the behavior of birds that spend years flying (or swimming) and feeding and, apparently, sleeping above or within the deep sea? Scientists were largely limited to studies birds in breeding colonies, at least those we knew about and that were accessible (and, if you think that’s a complete list, you haven’t read the news that came out this week about a new colony of Adélie penguins found in the Danger Islands, Antarctica). We didn’t know much about migration routes, foraging away from the breeding colony, and feeding during migration, in the water and in the air. Where do albatrosses and shearwaters (indeed, most seabirds) go during the years between fledging and breeding? Where does the female Emperor Penguin go after she has produced that one egg and handed it over to the male for incubation?

Technology to the rescue! An array of tools ranging from geolocators to satellite trackers to depth measurers to miniature cameras have been employed by ornithologists and biologists over the past twenty years, yielding scads of information. And, in Far From Land: The Mysterious Lives of Seabirds, ornithologist Michael Brooke relates it to the rest of us. This is essentially a survey of ornithological marine research told in the voice of one of its most passionate and experienced participants. It is not a book for every birder, but it will be a fascinating read for those who love albatrosses, shearwaters, petrels, storm-petrels–you know, tubenoses–as well as penguins, gannets, cormorants, and pretty much every bird family that spends most of its life at sea.

This account of seabird behavior is divided into eight chapters, organized according to the birds’ life cycle—First Journeys; The Meandering Years of Immaturity; Adult Migrations; Adult Movements during the Breeding Season; Wind and Waves (how they affect behavior); Stick or Twist? (patterns of consistency in migration and other behaviors); and Where Seabirds Find Food. The chapters are framed, first by an Introduction that briefly describes the birds included in Brooke’s definition of “seabird” (in addition to the birds I mention above, he includes gulls, terns, and phalaropes), the limited knowledge we had of seabirds before this wondrous age of research technology, and useful accounts of how today’s technological tools were developed. A concluding chapter, appropriately entitled The Clash, discusses the good and bad of seabirds and people and conservation issues.

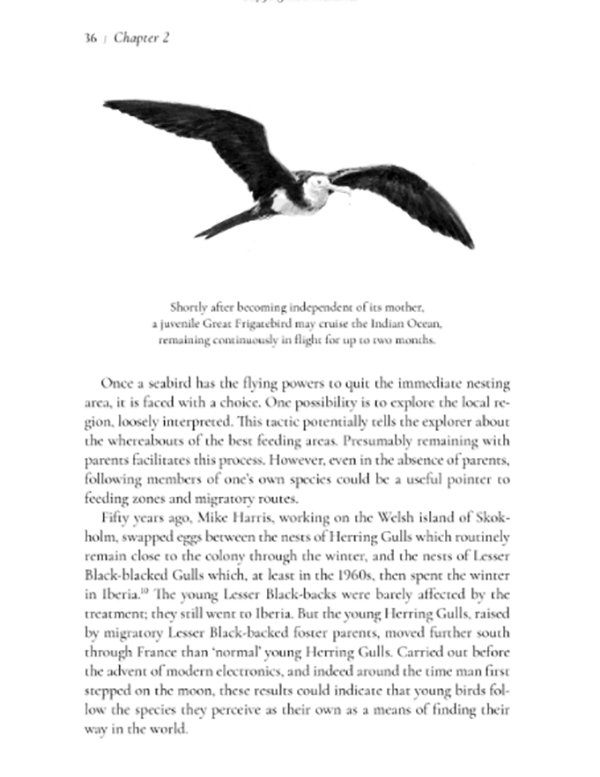

So, what did I learn from Far From Land? Some seabirds migrate incredibly long distances (Arctic Tern, Grey-headed Albatross, and, surprisingly, Ancient Murrelet); some don’t. Most migrating seabirds take advantage of prevailing wind patterns, but Sabine’s Gulls don’t–they fly a straight route north and south regardless of winds and we don’t know why. What about incubation shifts? For most seabird species, the male takes the first shift and the male and female then alternate, but the period of time for each shift varies according to species. Herring Gulls sit for up to five hours; Razorbills sit for one to two days; albatrosses sit seven to twenty days; a Murphy’s Petrel sits an average of 19 days while the mate travels thousands of miles, presumably looking for food, but scientists (including Brooke, who studied these petrels) don’t really know why. Frigatebirds are known for their piracy, but they actually get most of their food from hunting flying fish far out to sea, a fact determined by studies utilizing GPS trackers, heart-rate monitors, and accelerometers, all attached to the bird.

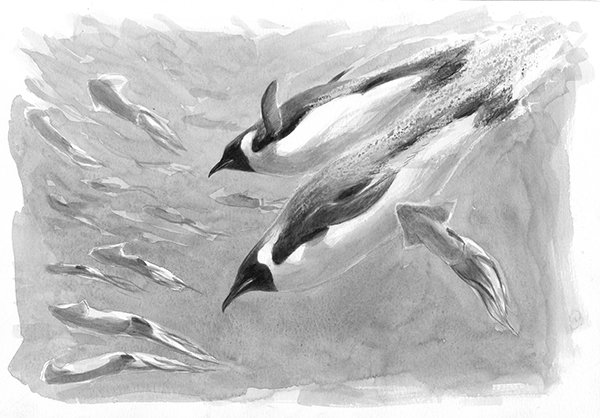

And, what about that female Emperor Penguin, who disappears for two months after handing her one egg over to her mate? Not very far from the colony, comparatively, according to studies utilizing satellite transmitters or time-depth recorders. They walk and toboggan to open water about 50 miles away and then hunt for food until it is time to come home and feed the chick. A little disappointing–no parties, no shopping, no love affairs.

Mostly, as you can probably tell from the last paragraph, I learned how a marine ornithologist thinks, and how challenging this research can be. Every study brings up new questions–many new questions–and Brooke spends a lot of text explaining why every study is specific, how there are really no generalizations to be made across the group of birds covered in this book. I learned that you can’t read about seabirds without knowing geography, and I frequently yearned for the globe my daughter used to keep in her room–Google Maps just won’t do when you’re trying to trace studies of birds in Great Britain, the Antarctic, and Christmas Island. And weather–winds, temperature of the sea, temperature of the air, ice–you can’t think about seabirds without thinking about weather and climate. (Surprisingly, few of the cited studies deal with climate change until the last chapter on threats and conservation.)

The book becomes most engaging when Brooke tells stories based on his or his colleagues’ experience. These instances are few, however, with most anecdotes related, almost apologetically, to the book’s prelude. It feels as though Brooke is trying very hard to make this book into a friendly, accessible natural history tale, but is constrained by ingrained rigors of years of scientific writing. Scientific conclusions take precedence, and if those conclusions are tempered by unknown geographic or climate or biological factors, then that must be explained as well. There are, though, brief, personal comments about scientists he admires, acknowledgements of studies with which he has been personally involved, and, best of all, a selection of the seabird rap delivered by Mark Maftei at the 2nd World Seabird Conference in 2015. Here are a few lines:

They’re so rare, they’re pink, just like a fine steak

And you might think you know them but you might be mistaken

Cos the fact of the matter is that no-one really knows,

Where the rarest little gull in the Arctic really goes.

(Brooke, p. 59)

Bruce Pearson is the book illustrator. Pearson has travelled extensively to the Falklands, South Georgia, and other seabird haunts and his black-and-white drawings, especially those of penguins, beautifully convey the birds’ habitats and activities. There are also photographs; the Princeton University Press catalog lists 29 photographs in color, but I can only find six black-and-white photographs in my pre-publication edition, so I cannot comment on what the final result will look like. Hopefully, it will include photographs of how the technology described so extensively here looks when attached to the bird. There are also a number of charts and maps interspersed throughout the text, helpful visuals for those of us trying to imagine the extreme, complicated migration routes and geographical tracts articulated by Brooke. I wish there were more!

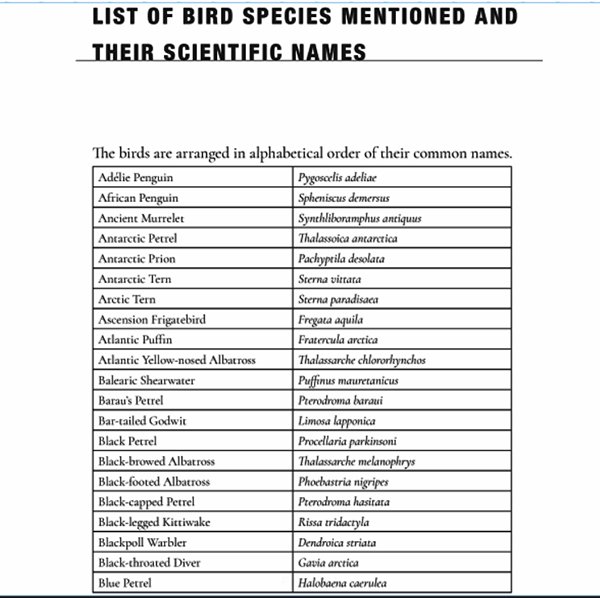

North American readers should note that British common names are used throughout. There is a footnote the first time ‘Brünnich’s Guillemot’ is cited in the first chapter noting the North American name ‘Thick-billed Murre,’ but that is easily missed. I’m surprised that the table entitled “List of Bird Species Mentioned and Their Scientific Names” doesn’t include a column for North American common names. There are few differences (Little Auk for Dovekie is the other one that comes to mind), but I can see this throwing off uninitiated readers. (Also, it would have been useful if the table separated out species considered “seabirds” by the author from other birds listed.)

Speaking of back-of-the-book materials, there is no bibliography. Instead, the studies Brooke summarizes and other resources are listed in an extensive Notes section. This is great, but I think a bibliography would have presented an organized, easy-to-use listing of studies for the birder who wants to follow up with the reading of primary source material, but who might not remember exactly where the book cited that study on “olfactory search in Wandering Albatross.”

I was unable to evaluate the book’s Index since it was not included in the preliminary text version I was sent for review. Hopefully, Princeton University Press will send me the finished version, because, you know, I love to examine indexes. And, with its coverage of multiple studies in each chapter, this is exactly the kind of book indexes were meant for.

Far From Land: The Mysterious Lives of Seabirds is a book about seabird research by a passionate seabird researcher. Michael Brooke has a long career researching and writing about seabirds (his doctorate was on Manx Shearwaters and he wrote Albatrosses and Petrels Across the World, Oxford University Press, 2004), and currently holds the position Strickland Curator of Ornithology, University Museum of Zoology, University of Cambridge. His goal, to articulate the advances made in seabird research utilizing technology, is fulfilled here, but often at the expense of bringing the birds themselves to life. I often found myself reaching for other books or researching species online to get a fuller picture of the many birds, many of them unfamiliar to me, cited in these chapters.

So, as I said in the beginning of this review, this is a very good book, a book that fills a niche, that addresses the need for titles about bird families that go beyond identification, but it is not a book for everyone. Who is it for? The seabird and gull fans (and I know there are a lot of you out there). The penguin fanatics. The passionate pelagic enthusiasts. Naturalists who love science and want a quick way of reading all the seabird articles in Condor, Marine Biology, and Seabird Conference proceedings. If you are traveling to some of the wondrous lands where you will be observing albatrosses, shearwaters, petrels, penguins, frigatebirds, and their relatives, reading Far From Land will enhance your birding experience; it will enlarge your scope of knowledge about the birds themselves and about the scientific effort and innovation involved in obtaining these new insights.

Far From Land: The Mysterious Lives of Seabirds

Michael Brooke, with illustrations by Bruce Pearson

Princeton University Press, March 2018

Hardcover, 264 pages, 21 color + 29 b/w illus. 8 maps

ISBN-10: 0691174180; ISBN-13: 978-0691174181

Great review, thanks. Coincidentally, this interview with the author showed up in one of my social media feeds.

http://blog.press.princeton.edu/2018/03/06/michael-brooke-on-far-from-land-the-mysterious-lives-of-seabirds/

Thank you for your review! I am looking towards a research project in the Funk Islands, as the subject of Seabirds is going to be very important in the next decades: the canary in the coal mine becomes the seabird in the Arctic. I will purchase this book as all research of the now dynamic area is highly valuable.