I came late to bird feeding, and when I was finally able to put out a “thistle” sock and a seed feeder (or two or six), I was amazed by the learning curve. Shelves of feeders to choose from, ranging from inexpensive tubes to porcelain sculptures; bags and barrels of shelled and unshelled seed, including something called variously thistle, nyjer or niger; guidelines on when, how, where to do the actual feeding. There was cleaning, lots of cleaning of feeders and yard. And squirrels. Aggravatingly, many squirrels. Who knew?

It turned out, many people. There is a long list of articles and books on how to feed birds in your yard. How to choose bird feeders; how to make nutritious bird food; how to create a backyard environment that will attract birds; how to survey your feeder birds for citizen science projects; how to prevent squirrels from gobbling up all your black oil sunflower seed (sorry, none of that works). But, not a lot of information about how this national passion (52.8 million people in the U.S. in 2011*) came about. And, few insights into the economic side of what is essentially a profitable industry. So, I was happy to see the publication of a book on all aspects of wild bird feeding—history, culture, and economics. And conservation. Maybe not as obvious, but probably the most important.

Feeding Wild Birds in America: Culture, Commerce & Conservation by Paul J. Baicich, Margaret A. Barker, and Carroll Henderson is a well-researched, copiously illustrated, engaging study of bird feeding practices, personalities, inventions marketing, and companies that developed in the United States from the late 19th century to the present day, with a little bit of Canada, Europe, and South America thrown in. It is a serious book with a friendly attitude. Written by birders, it underlies a wealth of facts, trends, and events with a consciousness that the more knowledgeable we are about good bird feeding practices, based on history and experience, the more successful bird feeding will be at bringing people to birds and the more people will advocate for effective conservation policies and laws.

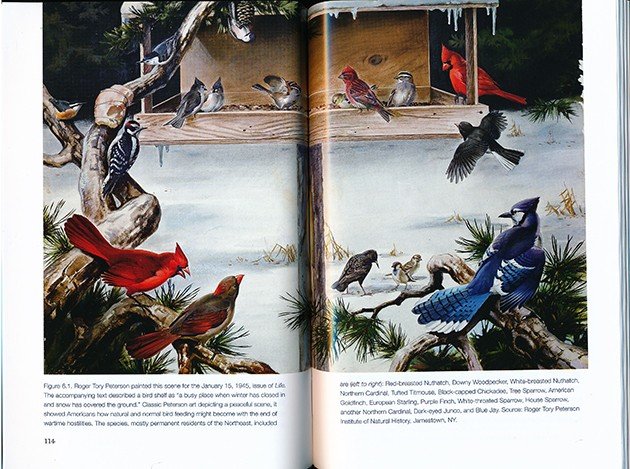

The book is organized historically, starting with Thoreau, who used corn to attract jays and chickadees to his doorstep, then jumping slightly ahead to the end of the 19th century and the bird protectionist movement, which advocated bird feeding both for study and for birds’ survival. Each decade of the 20th century is then explored, taking a close look at the development of wild bird feeding as an industry and a hobby, grounding trends within larger world events. The growth of community bird feeding programs in the 1920’s, for example, is shown to be rooted in post-World War I America prosperity–more spending money, more time, and (this is the part I like) the availability of cheap grain.

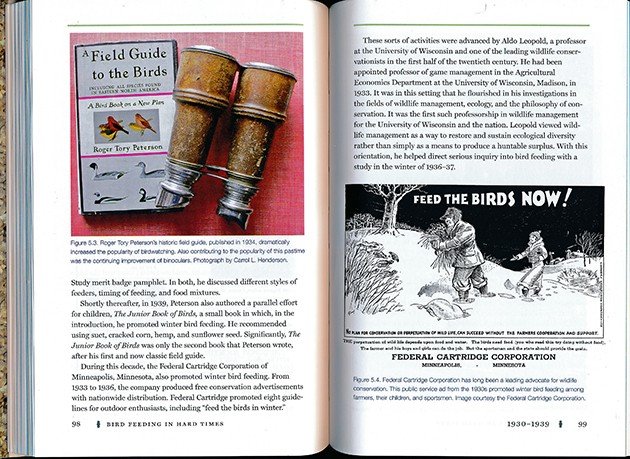

Some decades are richer in events than others, but it turns out that even periods of little forward movement, like the 1930’s hold nuggets of interest. There may have been a Great Depression going on, and little discretionary spending for bird seed, but this was the decade that saw the publication of A Field Guide to the Birds: A Bird Book on a New Plan by a young Roger Tory Peterson in 1934, followed by a second, less well-known title, The Junior Book of Birds, which advocated winter bird feeding.

The authors take as wide a view of bird feeding as possible, drawing on historical bird food recipes (my favorite is the 1907 Food Tree, which involved pouring a mixture of white bread, hemp, poppy flour, and ants’ eggs over a coniferous tree); product development history (the ubiquitous tube feeder was not invented till 1969); agricultural research (black oil sunflower seed development is a fascinating story of Cold War cooperation); ornithology (changing migration patterns are documented by and possibly influenced by feeders); and citizen science (the popular Project FeederWatch, which originated in Canada).

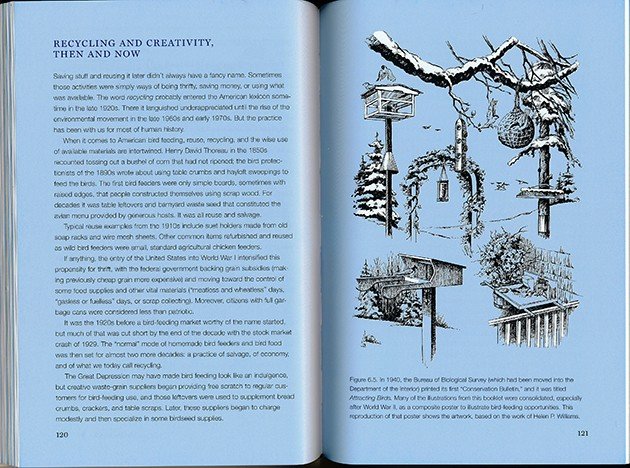

The chronological history is enhanced and enlivened by numerous “side stories” positioned at the end of the appropriate chapter on colored paper. I greatly enjoyed reading these articles on diverse topics such as suet, nyjer seed, the development of humming-bird feeders, rarities at feeders, wild bird feeding in Latin America and the Caribbean, and, importantly, “funding for birds and wildlife.” This is a smart way to approach a many-faceted topic like wild bird feeding. Articles such as “Recycling and Creativity, Then and Now” bring together material from across the decades to present snapshots of change (and non-change). Articles on citizen science, community feeding, and “windows, glass, and feeding stations,” help emphasize the connection between personal actions and the larger conservation picture.

I also enjoyed reading the company histories of familiar brands like Duncraft, Kaytee, Droll Yankee, and Wagner all of which started as family companies, some as offshoots of other businesses, some as the result of clever inventions. The story of Duncraft is a good example. Gilbert Dunn started creating bird feeders in his New Hampshire workshop because he wanted to do something connected to the outdoors and be self-employed. Although a carpenter, Dun used plastic to create Flight Deck, a handsome, versatile window feeder, and Flight Dome, a window feeder with a dome to keep pigeons (and, I bet, squirrels) away. Dun’s innovations included advertising in gardening magazines, growing mailing lists, and seasonal catalogs. These brief stories remind us that the bird feeding industry is made up of more than shelves of feeders and seed. It’s about packaging, marketing, distribution, transportation, and lobbying.

Feeding Wild Birds in America started off as a commission from Wild Bird Centers of America (WBCA), a retail franchisor. The authors’ interest expanded into this book, published by Texas A&M University Press. So, it’s not surprising that the bird feeding industry, which, “generates many billions of dollars in sales,” is treated postively in this book.** It is an industry that has supported bird feeding education, research and wildlife conservation through educational web sites, foundations and the initiatives of the Wild Bird Feeding Industry, the industry trade association. The authors’ attitude reflects the general relationship of nature lovers and bird feeding companies and retail stores– one of mutual support, even as we bird feeders bemoan the price of nyjer and squirrel-proof feeders. (We do know that we have a choice.)

I was surprised, however, that there is no mention of one of the dark spots in bird feeding history, the highly publicized application of toxic insecticides to Scott’s Miracle-Gro bird seed from 2005 to 2008 and the accompanying falsification of documents to hide it. Scott’s was fined $12.5 million by the EPA in 2012 and was sold to Global Harvest Foods in 2014. I do not understand why the sale is reported in one of the final chapters of the book but there is no mention of the corporate crime, the reason behind the sale. If any of the authors would like to respond, I would welcome an explanation.

“Bird Feeding in the Twenty-First Century: Experiences and Expectations,” the chapter in question, has other disappointing omissions. Specifically, there is no mention at all of the role social media has played in promoting wild bird feeding. Bloggers like Julie Zickefoose, Sharon Stiteler (Birdchick), and Laura Erickson have educated thousands of people about best feeding practices and other optimal ways to interact with nature since the mid-2000’s. (Julie actually is cited in the book for her wonderful Zick Dough, but there is so much more to say.) Facebook and Flickr, with their bird photography groups for birders and photographers of all levels, have encouraged people to pay more attention to the birds they feed.

And, there is, of course, the Internet itself, which offers lessons on how to feed birds from birding associations, bird feed companies, and individuals, in print, photographs, and video. (How do you think I learned how to run bird feeder stations at home and, for a while, at work?)

I am guessing that these, and other advances of this century had to be put aside in the interests of time and space. The chapter reads as if it was written after the rest of the book as a brief update, and is squeezed between the delightful chapter on Bird-Feeding Recipes Than and Now and before the concluding chapter on History Lessons for Modern Bird Feeding. The latter is an excellent summary of the state of the art of bird feeding from a unique historical point of view.

The authors obviously spent a lot of time researching this book and they list their major print sources in the back. Readers are referred to the text itself for citations of historical periodicals such Bird-Lore, the magazine that preceded Audubon magazine. This is too bad. Bird-Lore is available online, as are many of the field guides and bird books described in early 20th century chapters, and I think readers would enjoy knowing how to access and read these titles.

There in an index and it is lengthy, but it could be improved. There are entries for Erica, Gilbert, Mike and Sharon Dunn, for example, but no entry for their company, Duncraft. Some entries appear to have been made by a key-word computer program. “Wild Bird” is the entry point for several entries that should have been separated out—Wild Bird Centers of America, Wild Bird Feeding Industry, Wild Bird Feeding Institute, and Wild Bird Unlimited.

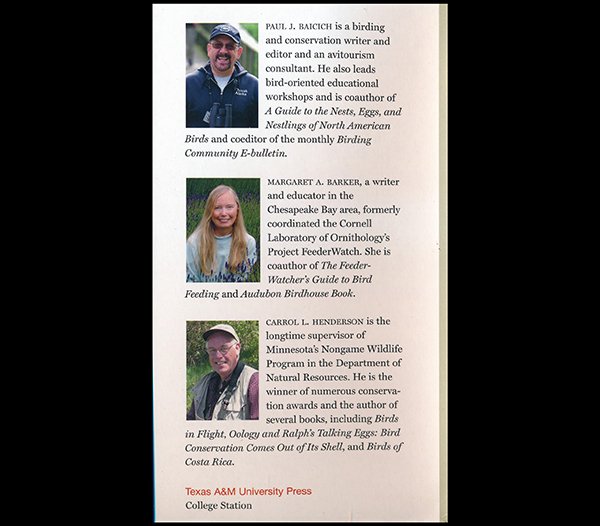

The three authors of Feeding Wild Birds in America are all well-known naturalists, writers, and editors. Paul J. Baicich worked for the American Birding Association from 1991 to 2003 as editor and Director of Conservation and Public Policy. He’s also worked with the National Wildlife Refuge System, co-led birding tours to Alaska, and co-authored A Guide to the Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds (1997). Margaret A. Barker formerly coordinated Project FeederWatch for the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, and is the co-author of The FeederWatcher’s Guide to Bird Feeding (2000) and the Audubon Birdhouse Book: Building, Placing, and Maintaining Great Homes for Great Birds (2013). Carroll L. Henderson is supervisor of Minnesota’s Nongame Wildlife Program in the Department of Natural Resources and the author and co-author of many books, including Birds in Flight: The Art and Science of How Birds Fly (2008), Oology and Ralph’s Talking Eggs: Bird Conservation Comes Out of Its Shell (2009), and Woodworking for Wildlife: Homes for Birds and Animals (2010).

The writers have created a good book. If you are one of those 58.2 million people who feed wild birds, Feeding Wild Birds in America: Culture, Commerce & Conservation is likely to enhance your enjoyment and expand your knowledge base. I know I will never be able to put out black oil sunflower seed again without thinking of V.S. Pustovoit, the Soviet agronomist who won the Order of Lenin for developing it (to help Russians survive a drought, not to feed birds!). And, I have a new appreciation for the range of labor and innovation involved in the bird feeding industry. I love feeding my birds, and there will be days when I’m content with that. And, then there will be the days when I will be happy to know I’m part of a community and a part of a very specific history.

——————–

*U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The 2011 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation, p.36, https://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/fhw11-nat.pdf. The survey is done every five years.

**Quote from the Forward is written by George H. Petrides, Sr., CEO and found of Wild Bird Centers of America.

——————–

Feeding Wild Birds in America: Culture, Commerce & Conservation

by Paul J. Baicich, Margaret A. Barker, and Carroll Henderson.

Texas A&M University Press, 2015.

320 pages; 8.6 x 6.5 x 0.8 inches.

ISBN-10: 1623492114; ISBN-13: 978-1623492113

Thank you to Texas A&M University Press for providing a review copy of this book.

Leave a Comment