New Year’s Day 2014. With binoculars around my neck, I am leaving home, wondering which will be the first species on my year list. On a parking lot, I pass by an invisible bird and continue to my local patch of the Ada Huja Danube Riverbank, where my first bird becomes the Rook. And yet, I have passed by one before that. The one I do not count. I do not notice. I do not write down. For a passionate birder, it must be an unusual behaviour? Or, is it?

Ornithology, as well as birding, deals with wild birds. While my invisible bird didn’t exactly walked out of a henhouse, it almost did. When I was a boy, I was fascinated with mediaeval citadels and still remember an illustration in some kids’ magazine depicting a castle with explanation of its parts. At the top of the tallest tower, there was one small tower with many holes. The explanation said: „dovecote – fresh meat in case of siege“.

Obviously, I am talking of Feral Pigeons (also called city, town or street pigeons). But they live freely – why aren’t they considered wild birds? Swallows, Martins, Black Redstarts, Rooks, even the Common Wood Pigeons – they all inhabit European cities and yet, no one would see them as anything else but wild birds. The scientific name of the Feral Pigeon is Columba livia domestica and that last world tells the story. Feral Pigeons are descendants of domesticated pigeons that escaped from dovecotes. In turn, those domestic pigeons were the first domesticated birds ever, bred for their meat from wild Rock Pigeons (or Rock Doves) in the Middle East some 6000 years ago. In other words, unlike the Common Wood Pigeons that have entered the city parks of my native Belgrade some quarter of a century ago, the Feral Pigeons haven’t entered the cities – they originated in them. Once escaped – or deliberately released, they quickly recognised city walls as suitable nesting cliffs.

By contrast, the wild Rock Pigeon, Columba livia livia, is an ill-numbered species that I have seen only a few times, in mountain gorges or Mediterranean islands, further away from villages. Unlike their feral cousins, such flocks consist of birds of same colours, pale grey with two black wing bars (usually, feral populations tend to retrieve their ancestral colouration, but not the Feral Pigeons). And yet, I cannot say with certainty have I ever seen wholly wild birds? If the DNA analyses of those birds that I observed were ever made, they would quite possibly confirm hybridisation with feral birds. It is not impossible that in my native Serbia (perhaps neighbouring countries too) we may not have any genetically clean populations of Columba livia livia left. Although the IUCN Red List classifies it as a Least Concern species, the hybridisation is a big threat for wild Rock Pigeons.

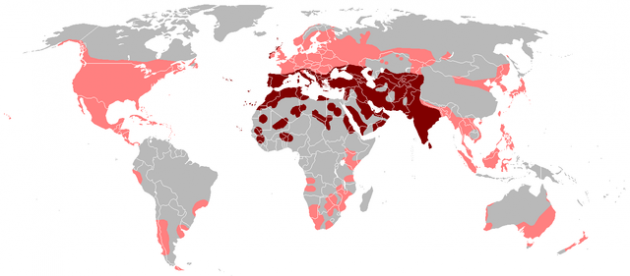

Dark red: approximate native range. Light red: introduced non-native populations (source: Wikimedia Commons).

Dark red: approximate native range. Light red: introduced non-native populations (source: Wikimedia Commons).

The range of Rock Pigeon includes remote parts of the Mediterranean, North Africa, Middle East, Central Asia and Indian Subcontinent. As domesticated birds were taken from one town to another, we no longer know the exact borders of the historic range of wholly wild birds. Once Feral Pigeons lived all over Europe, their export to former European colonies started, mostly as game birds (pigeon shooting was particularly popular in late 19th and early 20th century). Nowadays, Feral Pigeons inhabit all continents but Antarctica.

Since Rock and Feral Pigeons are often hard to tell apart, in areas where both overlap, the distribution of the Rock Pigeon is quite obscured, to say the least. eBird has recently made difference between the Rock and the Feral Pigeons, encouraging users to report both, but so far it is in mess and you cannot tell anything about Rock Pigeons (being reported from all over the world, where only the feral form might occur). The only thing one can tell is how far the Feral Pigeons reached. If both are treated together, populations are big and stable, but it is not clear what is happening with numbers of the wild Rock Pigeons and do we still have wholly wild birds at all?

How to determine the size or trend of populations of a species that we take no note of, usually (correctly) assuming that we are facing Feral Pigeons? It is my opinion that where both Rock and Feral Pigeons occur, birders should start counting and reporting them both in order to create a broad set of data to draw future conclusions from. From few observations of (uncertain) wild Rock Pigeons nowadays, we may draw only guesstimates.

Whether we like Feral Pigeons or not, they are here to stay. It just may be the time to – get to know them?

Cover photo (c) S. Panjkovic

…

Here at 10,000 Birds 20 July – 26 July is Invasive Species Week. We use the term “Invasive Species” in the broadest sense, to encompass those invasive species that have expanded beyond their historical ranges under their own power, by deliberate introduction, or by unintentional introduction. The sheer number of species that have been shuffled around on our big earth is impressive, though we will be dealing with the smaller sample size of invasive avians and other invasives that effect avians. Nonetheless, this week will be chock full of invasive species. So batten down the hatches, strap on your helmet, and prepare to be invaded! To access the entire week’s worth of content just click here.

Here at 10,000 Birds 20 July – 26 July is Invasive Species Week. We use the term “Invasive Species” in the broadest sense, to encompass those invasive species that have expanded beyond their historical ranges under their own power, by deliberate introduction, or by unintentional introduction. The sheer number of species that have been shuffled around on our big earth is impressive, though we will be dealing with the smaller sample size of invasive avians and other invasives that effect avians. Nonetheless, this week will be chock full of invasive species. So batten down the hatches, strap on your helmet, and prepare to be invaded! To access the entire week’s worth of content just click here.

Thanks for an interesting post and map! You’re so right that these birds are invisible to us.

While writing this, I had to check my Southern African List to see if I had seen any Feral Pigeons there. I do remember many bird sightings from Africa, yet, do not remember that. But i did wrote it down: Feral Pigeon Columba livia domestica, Gaborone, Botswana 4/Jun/99

As I read this post I looked out my window and saw part of my local pigeon flock fly by. Though they can be a nuisance they make me happy because they are one of the few species that I am guaranteed to see every single day.

I thin kthere are very few bird species native to Germany that we know so little about as the Feral Pigeon. Which is a shame, as they’ve been around for so many centuries and are an important part of urban and sub-urban ecosystems. I’ve frequently tried to convince other birders of counting/mapping pigeons, mostly to no avail.