The first thing to note about the Field Guide to North American Flycatchers is the subtitle: Empidonax and Pewees. No Kingbirds, no Phoebes, no Myiarchus flycatchers, just Empidonax and Pewees. The second thing to note is that this is an excellent and courageous book that tackles a group of birds whose field identification has stumped the most skilled birders. Gulls and sparrows are tough but manageable; Empids may require DNA analysis (as it actually did in the case of the non-vocalizing Western Flycatcher seen in Central Park, NYC in November 2015). The book expands field guide boundaries with its narrow focus on two genera (groups) with a bonus Tufted Flycatcher thrown in for good measure. That’s 18 species in one book. I don’t know another guide that is more specific, and, in what I like to think of as the golden age of field guides, it’s an intriguing direction. The third thing to note about Field Guide to North American Flycatchers: Empidonax and Pewees is the care authors Cin-Ty Lee and Andrew Birch have taken to present their identification expertise in a way that is understandable by birders of every level.

This is more than a collection of species accounts. The authors spend a significant portion of the book (42 pages) on HOW to observe flycatchers, a process involving the observation and analysis of a number of field marks including structure and shape, habitat, range, and, of course, vocalizations, and which they call “holistic field identification.” This builds and expands on a classic series of articles by Bret Whitney and Kenn Kaufman that appeared Birding magazine between 1985 and 1987.* Whitney and Kaufman start the series by describing a state of confusion in Empid identification: “Many supposed fieldmarks have been suggested and have been widely quoted or misquoted, with birders taking sides on each one, claiming that one character is diagnostic while another is worthless. Even those points that seem to be universally accepted are often more opinion than fact.” They conclude that many non-vocalizing Empidonax flycatchers can be identified in the field, but only “when several field characters are used in combination–and after one has gained experience in looking at these characters on singing/calling and captive birds (i.e., known-identity).”**

Introductory Material

The problem is that many of these field marks are subtle, difficult to distinguish in the field, and also that many birders, not only beginners, don’t know what to look for. Lee and Birch smartly start off with a chapter that names, describes, and illustrates these traits: Crown Shape, Forehead Angle, Bill Length, Lower Mandible Color, Tail Length, Tail Width, Primary Projection, Wingbar Contrast, Wing Panel Contrast, Upper/Underpart Contrast, Eye-ring, and Overall Coloration. (The chapter is titled “How to Use This Guide,” but don’t be fooled, it’s much more.) These descriptions are immensely useful, telling us which field marks are diagnostic and which are variable within a specific species, which ones might vary under different lighting conditions or the bird’s state of molt or age or sex, which field marks are useful for pewees but not for Empids, and more. Plumage color, for example, is subject to a great deal of variation, as anyone whose seen and photographed a flycatcher in direct sunlight and then under a cloud can attest–gray-green? green-gray? gray-brown?–it’s lighting and our own individual perceptions in play. The authors recommend observing “color contrasts between different parts of the bird” instead of simply looking at overall coloration (p. 30).

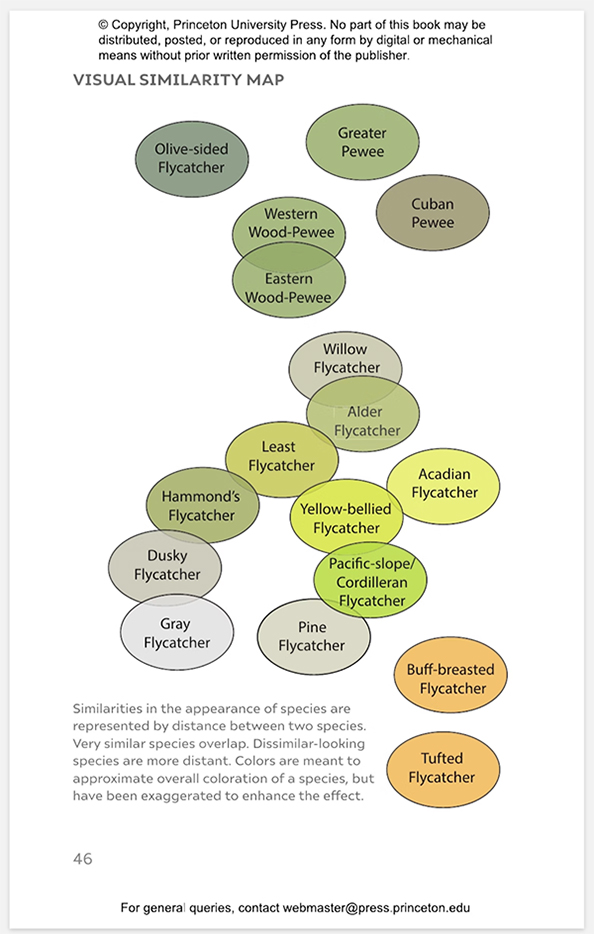

This chapter also talks briefly about Behavoir, with special attention to wing and tail flicking; Age and Molt; Vocalizations and how to read spectograms (included in the Species Accounts); Habitat Preferences; and, in the section on Range, Seasonal Status, and Migration, how to read the Species Account range maps and seasonal abundance charts, important clues to identification. To bring it all together, the authors present two unique visual aids: a Field Mark Matrix, a chart plotting out significant field marks, including tail and wing flicks, for each species, and a Visual Similarity Map (below), which shows in graphic form which flycatchers look alike and which do not. There are also two pages illustrating the “Holistic Approach,” silhouettes of each species (Western birds on the left, Eastern birds on the right), that allow for comparison of structure, size, and shape.

Species Accounts

Species Accounts vary in length according to the bird, with similar looking species (Western and Eastern Wood-Pewee, Willow and Alder Flycatcher, Pacific-slope and Cordilleran Flycatcher) treated together. As I said above, 18 species are covered, all members of the Empidonax and Contopus genera plus Tufted Flycatcher, which is in the Mitrephanes genus. I was puzzled why the authors decided to include Buff-breasted Flycatcher, Pine Flycatcher, and Tufted Flycatcher, species that have extremely limited range in North America. The answer for the first two, I imagine, is completeness, a desire to cover the whole genus. Tufted Flycatcher, the authors say in the Introduction, is included “because of its superficial resemblance to some of the Empidonax flycatchers” (p. 6), which I can confirm is true, having seen it in Carr Canyon, Arizona. It does get confusing, though, because the Species Account says that it is “unlikely to be confused with any other flycatcher in the United States” (p.51). At any rate, the inclusion of these species, which are seen in Mexico and Central America, does make this a ‘North American’ field guide in the true ‘North American’ definition of the geographic term.

Each species account is headlined with the common and scientific names of the species and its measurements and weight; suitably, Willow and Alder are under the heading ‘Traill’s Flycatchers’ and Pacific-slope and Cordilleran are under “Western Flycatcher.” Sections cover General Identification (size, shape, structure, what field marks to look for, behavioral clues); Voice (songs and calls are described and transcribed); Range and Habitat (habitat preferences on breeding and wintering grounds, times of spring and fall migration and where); and Similar Species (details on differences make this a very important section).

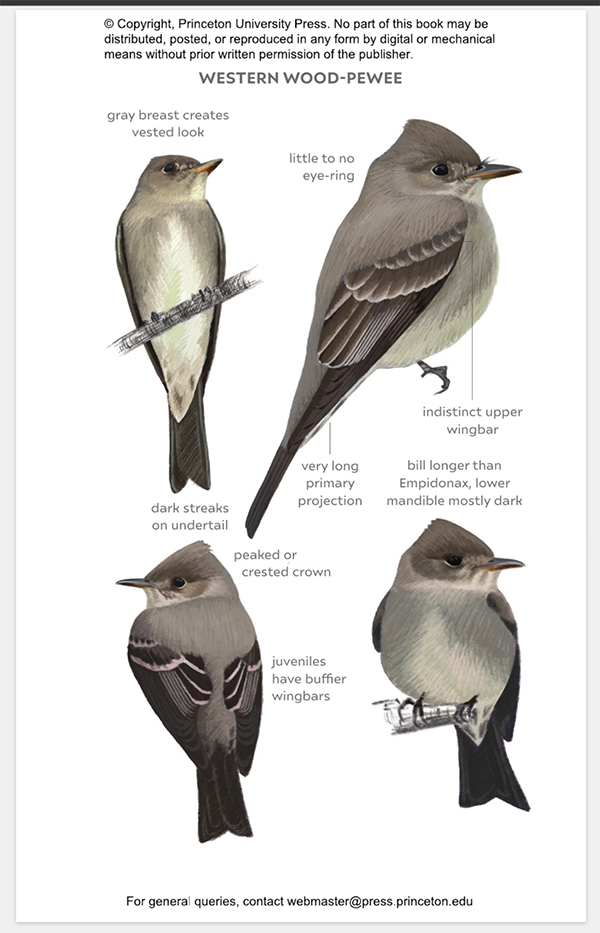

This is followed by a page or four of Andy Birch’s lovely, detailed illustrations. The species is shown mostly in profile, but also from the front or angled towards the front, and often angled towards the back, each image clearly created with the specific goal of illustrating a specific feature–the shape of the crown, the crispness of an eye-ring, the length of the primaries. Looking over these flycatcher images–all showing a perched passerine with wingbars and a yellow/orangish bill (o.k., sometimes very dark yellow/orange), all using the same muted palette of green, yellow gray, and brown–it becomes easier to see the structural and detailed differences amongst these species. It’s also a bit awe-inspiring, because creating these images must have involved hours of observation and, I imagine, museum work, and I wonder if at some point green-gray-brown fatigue set in. It’s easy for us to say that a field guide of neotropical birds features beautiful artwork. It’s harder, I think, to value artwork where the size and clarity of an eye-ring and the breadth of a tail distinguishes a species.

The images are large, with just three or four figures filling the page, and captioned in detail. This would be a luxury in most field guides and is one of the advantages of such small species coverage. I appreciate the addition of pencil drawings in some species accounts to illustrate structural features. Visual comparisons are made with similar species, such as the placement of a Willow Flycatcher image in the Wood-Pewee Species Account–we see full images of each species and pencil depictions of the primary projection differences. “Comparison of Hammond’s, Dusky, Gray and Least Flycatchers,” a seven-page subsection following the Dusky Flycatcher Species Account, is a visual tutorial is how to differentiate amongst these four species, all of whom appear in the west and, though frankly I think I would still have problems in the field.

This is why vocalizations are so important. The spectograms in each Species Account visualize the bird’s calls and songs, sometimes two or more of each (there are dawn songs and evening songs). I find them difficult to see on the page, and I’m not sure if this is because of the nature of the source material or if more contrast was needed when printing, or if it’s me (they actually do look clearer when I take my glasses off). Users might want to supplement the material here with the spectograms in Nathan Pieplow’s Field Guide to Bird Sounds regional guides and with the Merlin app in the field. The spectograms are most useful when read with the text descriptions, which explain which vocalizations are diagnostic, describe geographic variations, and when the spectrogram is especially necessary for differentiating similar vocalizations of different species.

The last feature in each Species Account are the range maps and abundance charts, illustrating and expanding on the information given in the text section. The maps are fairly complex, showing breeding range, winter range, year-round range, migration routes, times, and directions. Large and colorful, they include Mexico, Central America and sometimes South America, showing the full migration route. It would have been useful to have the map key on one of the inside covers, instead of page 41 (though the color-coding system is very simple). I like that there are abundance tables for several different locations, north to south, and that they are connected by arrows to the geographic locations on the range maps. I selfishly would have like more attention paid to New York on these tables and maps, though logically that makes no sense since most Eastern flycatchers take the Gulf of Mexico migration route.

Authors

Authors Cin-Ty Lee and Andrew Birch are birders and birding writers and artists (Lee is also a very capable painter of bird images, as evidenced on his website) with roots in southern California. They have co-authored a number of articles, including several on field identification for Birding and Texas Birds Annual. Lee is also a geochemist and professor in the Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences at Rice University, Houston. Birch is well-known in the Los Angeles birding community (I had the pleasure of meeting him several years ago at Silver Lake Reservoir, where he showed me where to look for the long-staying Lucy’s Warbler). He is one of the leaders of the new Los Angeles Birders group, and has webinars on topics such as “Tricky Tringas” and, with Cin-Ty Lee, “Empidonax Identification in the West.” He is a co-illustrator of Field Guide to the Birds of the Middle East (1996) and has illustrated many other magazines and articles.

Conclusion

Field Guide to North American Flycatchers: Empidonax and Pewees a well-thought out, handsomely designed guide to the process of flycatcher identification in two of its most challenging groups. The book is no magic wand–studying it may not result in instant identification of the next Empidonax flycatcher you meet, though it may help you distinguish it from a Wood-Pewee. It will teach you what field marks and behaviors to look for, observe and photograph, and it will provide a vocabulary and framework for how to work out that identification. As Whitney and Kaufman pointed out in those articles written over 30 years ago, one part of flycatcher identification is knowing which combination of field marks to use, the other part is experience.

This is a book well worth owning for both its excellence of content and uniqueness. There are not a lot of flycatcher guides out there! (I found a recent title, Lazer Focused Field Guide to the Flycatchers of North America by Texan birders Mark Cochran and Mel Cooksey, independently published, but have not been able to examine it and can find no reviews.) Kaufman’s chapter on”The Empidonax Flycatchers” in his Field Guide to Advanced Birding (2011) covers a lot of the Empid material, but much more compactly (40 pages) and without the helpful Field Mark Matrix, spectograms, range maps, and easy-to-use design of the book. The guide is reasonably priced (at $19.95, figure it’s $1.11 per bird), light and portable, and, with minimal technical language, geared to birders of every level. Field Guide to North American Flycatchers: Empidonax and Pewees is hopefully the first of a three-part series on flycatcher identification, according to the authors. I’m curious how the remaining Tyrant Flycatchers of North America will be divvied up–Kingbirds and Kiskadee? Phoebes and Myiarchus? A special section for the stunners–Scissor-tailed, Fork-tailed and Vermillion Flycatchers? And what new identification “cheats,” like the Field Mark Matrix and Visual Similarity Map, Lee and Birch will devise. And what Andy Birch’s artwork will look like once he’s able to use a little more color. It’s something to look forward to.

* This five-part series is now retrievable for members of the American Birding Association thanks to the digitization of all issues of Birding. The Birding magazine archive can be searched by keyword, title, or author or by clicking on the thumbnail of the wanted issue’s cover. The “Empidonax Challenge” articles are in the following issues: Part I–August, 1985; Part II–Dec. 1985; Part III–June 1986; Part IV–Dec. 1986; Part V–Oct. 1987.

** Whitney, Bret & Kenn Kaufman, “The Empidonax Challenge: Looking at Empidonax, Part I,” Birding, v. 17, no. 4, Aug. 1985, pp. 151-152.

Field Guide to North American Flycatchers: Empidonax and Pewees

by Cin-Ty Lee and Andrew Birch; Illustrated by Andrew Birch

Princeton University Press, April 2023

157 pages; 5 x 8 in.; illus: 55 color + b/w illus. 19 maps. 53

ISBN: 9780691240626

$19.95/£16.99

Thank you for this review. I’m looking up the references for the original Whitney/Kaufmann articles (thank you again!). I notice that in the first article, they write that they intend to have *6* parts, with the 6th part covering the Mexican empids of White-throated, Pine, and Yellowish. I’ve not found any additional references to that mythical 6th part — do you know if it was ever published?

Hi Eric–That’s a very good point and I don’t have a good answer. I don’t see this article in Birding magazine and all references to the series say it has five parts. I will do some more research.