Mathias Kom is the primary singer and songwriter behind the Canadian cult folk band The Burning Hell. He has long been interested in birds, but, particularly with the 2022 album ‘Garbage Island’, birds have taken a more prominent role in his songwriting. He lives and writes in rural Prince Edward Island, Canada.

The first song I ever wrote about a bird was called “Little Seagull,” long before I had any idea that the word seagull was a heinous colloquialism that no self-respecting bird lover would ever use. I wrote it while sitting with a cheap ukulele on a beach near Corpus Christi, Texas (not far from the northern edge of Padre Island National Seashore, one of the most renowned birdwatching locations in the southern US). Listening to the sound of the gulls all around me, I was struck by how our evaluations of birdsong are filtered through such a subjectively human – but also profoundly cultural – lens. How do we decide what makes a particular song or call beautiful, and others less so? The little song came out of me all at once, a bouncy, silly three-chord thing with a bridge that ends with a twist:

Why don’t seagulls ever sing?

Are you too busy doing other things?

Just one flap of your seagull wings

And the world is destroyed

That was back in 2007, and since then I’ve written and recorded dozens of other songs, with a scattered reference to birds here and there. But it wasn’t until I moved to the shores of rural Prince Edward Island in 2015 that birds started appearing more often in my work. I live within sight of a rocky sandstone beach, and my daily life for the last decade has been accompanied by gulls of all sorts, but also bald eagles, Northern gannets, cormorants, several species of tern, various plover, sandpipers, and all the other usual and sometimes unusual suspects you’d expect to find on the shores of Eastern Canada. In the woods and fields around my house, blue jays and chickadees and Northern harriers are my reliable neighbors, and Ruby-throated hummingbirds are my constant gardening companions. A few kilometers down the road is East Point, which is one of the best birding spots on the island, well-known as a resting place for migrants and unexpected guests, like the crested caracara that showed up last year and spent the better part of three months sitting in a tree gorging on the lobster carcasses a local farmer helpfully piled up a nearby field.

It’s not uncommon for songwriters to incorporate aspects of the world around them into their work. The streets of New York are almost a main character in the songs of Lou Reed, for instance, and countless Californians, from locals like the Beach Boys to imports like Joni Mitchell, have created a sonic image of the state that looms large in the collective consciousness of millions of people who have never set foot there. It’s hard to imagine soul music without the urban grit of Detroit and Memphis, classic and contemporary country without the romanticized dirt roads and roadhouses of the rural south, and so on.

But birds are something else entirely, and their simultaneous ubiquity and diversity means that everyone everywhere has at least some relationship with them. This has almost certainly been true since before humans were humans. The oldest musical instrument in the world is a 60,000 year-old bear-bone flute made by our Neanderthal ancestors in what is now Slovenia, and it’s not hard to imagine that Neanderthal musicians would have been at least partly inspired by the songs of the birds around them. The history of music-making is completely intertwined with birdsong, from ancient folk tunes to Mozart to Kate Bush, and examples can be found in every human culture. While studying for my PhD in ethnomusicology, I was struck by the now-classic ethnographic work of Steven Feld, Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics and Song in Kaluli Expression, which details the remarkable ways that the Kaluli people of Papua New Guinea incorporate birdsong into their daily lives. While the Kaluli provide a uniquely rich example, one of the impacts of Feld’s work was to bolster the emerging field of acoustemology – the anthropology of sound – and the understanding of just how deeply interconnected human sound-making practices are with the natural and built environments we work and play in.

But I won’t pretend I was thinking about any of that, even for a minute, when I wrote the songs that eventually became Garbage Island. Instead, I had read an article about the Great Pacific Trash Vortex, which suggested an incredible image of the massive gyre of garbage as an actual landmass, a mountain of plastic emerging from the sea. Of course, the reality is that the various trash vortexes our runaway consumption have created are made up mostly of microplastics and small bits of marine debris that are constantly in motion, but I was drawn to the idea that rising sea levels and the eventual collapse of what we hilariously call ‘civilization’ would one day lead to a Waterworld-like planet, with nothing but ocean for miles, interrupted only by a small island made of our own refuse and populated mostly by birds.

This imagery was so compelling to me that I started writing songs around it, beginning with “Bird Queen of Garbage Island”, the first-person narrative of the imagined ruler of the new world demanding obeisance from her subjects:

Gannets and gulls, petrels, puffins and pelicans:

Make me a temple of nets and fish skeletons

Next take the buoys, bottles, dongles and ping pong balls

Build a wall all along the horizon and ten times as tall.

I lost an eye to an albatross with mischief in his heart

But I replaced it with this ball-bearing painted to look the part

I’m a leader with a singular vision, or if you prefer, a cyclops tyrant

All hail the Bird Queen of Garbage Island

Another newspaper article inspired the song “Nigel the Gannet”, not a denizen of Garbage Island per se but a real-life gannet in New Zealand whose eulogy made the papers. Nigel was dubbed the “world’s loneliest bird” because he lived alone with a concrete gannet decoy he had taken as his mate. But I wondered if perhaps Nigel knew exactly what he was doing, and was simply the gannet equivalent of the hermit who turns their back on their fellow humans, preferring solitude to society:

The bird-banders fill binders and books with his biography

They note his habits and record his squawks on dictaphones

Meanwhile Nigel wonders “why don’t they ever ask me?

I could tell them there’s a difference between being lonely and being alone.”

The scientists published papers and secured some grants

To repopulate Nigel’s future neighbourhood

With a concrete caster named Carl they concocted a plan

But they couldn’t have predicted Nigel’s commitment to bachelorhood

Called to the concrete colony by a cassette

Nigel noticed the other birds didn’t fly or flap around

He remembered an old French peacock had told him “hell is other birds”

He thought “Well, this is just the kind of place I’d like to settle down!”

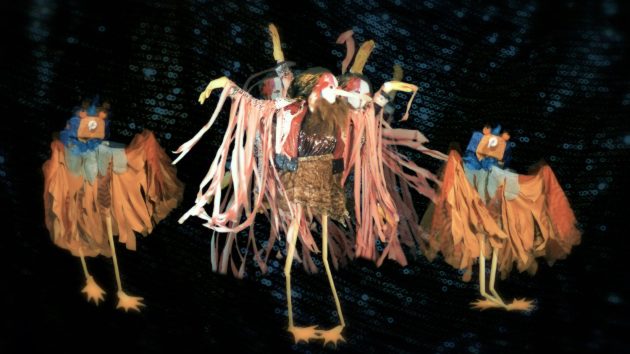

Illustration: Ariel Sharratt

All the time I was writing these songs I was discovering a new appreciation for the birdlife all around me. Like so many of us, the pandemic forced me to stay home, and I inevitably started to notice things I hadn’t really appreciated before, like the way the local crows would harass eagles four times their size, or the complexity of the hierarchies among the various gulls at the shore, or the incredible diversity of the communication between chickadees. My partner and bandmate Ariel Sharratt bought me a pair of decent binoculars, and I gradually took my first amateurish steps in the world of birding. I discovered very quickly that I had no real appetite for lists and no talent for photography, but I could happily watch our feathered neighbors for hours and not get bored of it. I began to think of the act of birdwatching itself as a metaphor for our best human impulses, a passive sort of resistance to the hyper-consumption, distraction, and speed of 21st-century life. With “Birdwatching” I tried to distill these thoughts into a two-minute rapid-fire punk song:

There’s a flower in the compost and a beach below the pavement

We’ll outlive the rich and famous if we remain aimless and patient

We’re neither rising like a phoenix nor dying like the dodos

So let’s leave the endless questing to the Sams and to the Frodos

Anthems are anathema, enough with rousing choruses

And achieving is as torturous as tickling slow lorises

The search for more and better gives us worse and fewer options

So let’s quit while we’re behind, and do some birdwatching

Entrepreneurship is capsizing and it will surely sink

Jump and swim to Garbage Island and just sit and have a drink

While everybody else is busy polishing their coffins

We’ll be mixing cosmopolitans, and birdwatching

Towards the end of compiling and recording the songs on Garbage Island, I knew I wanted to suggest the seeds of a future utopia inside the horror of apocalypse, the idea that in our own self-destruction, we might find a way to re-balance our existence with, rather than against, the natural world. On the penultimate song “Speechlessness,” the unnamed human protagonists slowly stop speaking and spend their time in observation:

Life’s a beach now, and that’s no longer an expression

The air above us is filled with wings in every direction

The years go by we watch them migrate and return

To everything there is a seabird, tern tern tern

I’ve always been drawn to concept albums, especially when they touch on various iterations of the apocalypse, and I remain enamored with birds. I’ve just finished a new album with my band, which will be released in the spring of 2025. It’s less directly about birds than Garbage Island, but birds do make their appearance as narrators and bystanders, and even protagonists. There are songs partly inspired by the work of ornithologist Richard Loyn, who we met while on tour in Australia in 2023, and who took us birding around his home and explained some of his research at the sewage treatment plant in Werribee, which has – thanks to our own human waste – become an unlikely birding hotspot. Elsewhere, an unnamed LBB / LBJ is the last creature to carry a memory of human beings, but they promptly forget all about us when distracted by a shiny piece of string.

And so on. I can’t imagine ever devoting all of my songwriting efforts exclusively to birds, but neither can I imagine my songs without them. Writing about birds has led me down new paths, both creatively and literally, and connected me with fellow bird lovers all over the world. Birds were around long before we were here, and in spite of our best efforts at destroying them, will be around long after we’re gone. I feel privileged to share a world with them, if only for a little while.

The Burning Hell are one of my favorite bands in the world, and I am very proud to have Mathias contribute a guest post for 10,000 Birds. One of my old friends described it as “crossover” – linking my love of birds with that for alternative music. If you read this, please make sure to check out the music of The Burning Hell! You can do so at their band website https://www.theburninghell.com/

Garbage Island is a brilliant record that rewards repeated listens.

Garbage island is one of my all time favorite albums, it’s such a marvel of story telling and I find it impossible to sit still for a lot of it. Can’t wait for the new record!