Falconry Month at Birds and Booze:

I’ve decided to dedicate this month of March 2019 to wines and beers related to the history of falconry – or hawking – for no other reason than that I’ve recently acquired several bottles adorned with mostly medieval European iconography relating to this “sport of kings”. While the hunting of game with trained birds of prey can be a controversial topic among birders, falconry was a valuable early source of information on birds, and its history, culture, and imagery continue to fascinate bird lovers, as we shall see.

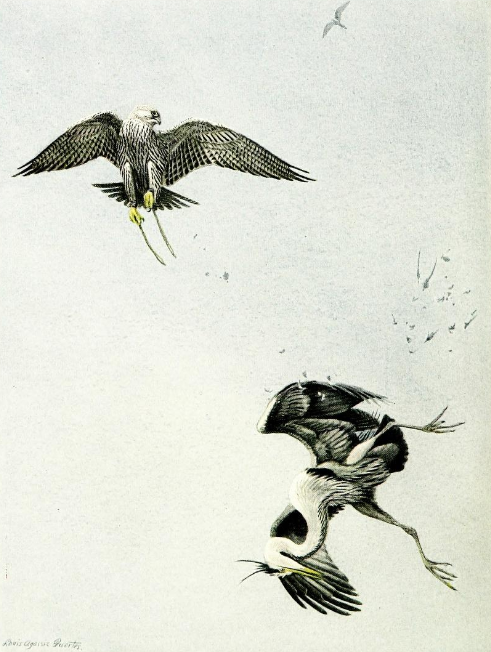

The Gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus), the largest falcon in the world, is as sought after by falconers as it is by birders – and for many of the same reasons: namely, the rarity with which these imposing raptors of the Arctic visit us residing in more temperate climes. But they are also highly-prized for their ruthless and powerful efficiency in killing – medieval illustrations depict them downing cranes and a twentieth-century painting by Louis Agassiz Fuertes shows a falconer’s Gyrfalcon inflicting a lethal strike on a Gray Heron (Ardea cinerea).

Gyrfalcons have long been prized for their ability to hunt prey considerably larger than themselves, as depicted in this painting by Louis Agassiz Fuertes, where the unlucky victim is a Gray Heron (note the jesses on the falcon).

Because of their rarity, hunting prowess, and the great effort and expense expended in procuring them, possession of Gyrfalcons in the Middle Ages was often restricted to royalty in both Europe and the Muslim world. According to the 13th-century historian and geographer of Al-Andalus, Ibn Sai’d al-Maghrib’ (1213-1286), the Gyrfalcon was so highly esteemed that the sultan of Egypt was willing to pay 1,000 dinars for birds delivered to him alive – and half that amount even if they were dead upon arrival. Remarkably, al-Maghrib’’s Kitab al-Juhrafiya (Geography) even makes mention of Ireland and Iceland, islands at the edge of the known world at the time, and identifies these places as sources of this coveted falcon.

To a royal buyer, one of the great selling points of the Gyrfalcon is the variety of colors they come in – particularly the striking ermine plumage of the palest birds. The 14th-century Castilian chronicler Pero López de Ayala (1332 – 1407) notes that Gyrfalcons in this coloration were known as letrados (“letters”) for their resemblance to pages of calligraphy, and were often kept merely as royal decorations.

Image: Portrait of a Gyrfalcon, Viewed from Three Sides, by the Lombard Master (fl. 1540 – 1560)

After its colonization by the Norse in the late ninth century, Iceland soon became a lucrative source of Gyrfalcons destined for the courts of Europe and beyond. Here they bred in even larger numbers than in the fringes of northern Europe in Britain and Scandinavia, making the troublesome capture of eyasses from their remote eyries a profitable venture for centuries. By the 12th century, Gerald of Wales (Giraldus Cambrensis) noted that “this land [Iceland] produces and sends large and noble gerfalcons”. And as we saw in our first encounter with the 13th-century Holy Roman Emperor, letters from Frederick requested the delivery of Gyrfalcons from Greenland to his court in Palermo – an extraordinary example of the vast scope of the medieval trade in these birds.

Collecting Gyrfalcon chicks from their eyries in the wild was difficult work, as shown in this manuscript illumination from De arte venandi cum avibus.

Though falconry appears to have been Frederick’s greatest passion, we also know that he had an apparent interest in wine, as he encouraged the cultivation of the ancient Aglianico grape in his southern Italian homeland. Whether any wine from Frederick’s vineyards in Basilicata or Campania made it to far-off Reykjavík in exchange for sending its Icelandic Gyrfalcons south is unknown. But we can imagine that at some point – at least within Frederick’s Sicilian realm – both Arctic falcon and Mediterranean wine were unlikely companions at court (and perhaps in the field, as well). Perhaps this ancient connection can explain the wholly unexpected appearance of a Gyrfalcon on the label of this week’s wine: the 2016 Aglianico del Vulture “Gricos” from the Grifalco (“Gyrfalcon”) vineyards run by the Piccin family near Monte Vulture in Basilicata.

Exactly why the name Grifalco was chosen by this Basilicatan winemaker is unknown. But for a third week in a row, we’re enjoying a southern Italian red wine made from the Aglianico grape and packaged in a bottle adorned with the falconry iconography of the Middle Ages. Perhaps it’s only coincidence, but it seems more likely that the enormous legacy of the Hohenstaufen emperor Frederick II – born of a German imperial house but by all accounts a Sicilian at heart to the end of his days – still looms over the culture of the Mezzogiorno and its winemaking so many centuries later.

The lovely gyrfalcon image on the Grifalco label of this wine is not from any ancient source I can identify, but it is certainly medieval in spirit, recalling the Insular illumination of the Book of Kells or the Lindisfarne Gospels in its gilded abstraction.

Like the two previous Aglianico bottles we’ve tasted, Grifalco is a brawny young red wine and could easily benefit from several years of aging. The “Gricos” Aglianico is the most straightforward wine from Grifalco, made from the youngest vines of the estate. This 2016 bottling has a bold and fresh bouquet, with the sweet and tart aroma of raspberry jam, deeper hints of prunes, and earthy touches of star anise and myrtle. The palate is fruity and zesty but reined in by firm and polished tannins and a generous acidity that should allow this wine to mature nicely in the coming years.

Good birding and happy drinking!

Grifalco: Aglianico del Vulture “Gricos” (2016)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Four out of five feathers (Excellent).

Leave a Comment