Dr. Roberta L. Bondar is globally recognized for her pioneering contributions to space medicine research, fine art photography, and education on the environment. Aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery mission STS-42 in 1992, she conducted experiments in the first International Microgravity Laboratory, a precursor to the International Space Station. Trained by NASA’s Earth Observations team, she also photographed the Earth while circling it 129 times. Dr. Bondar later became an honors student in professional nature photography. For her Passionate Vision project, she photographed, with medium- and large-format film cameras, each of Canada’s national parks; for The Arid Edge of Earth, she photographed global arid landscapes and their World Heritage Sites. Private, corporate, and institutional collections in Canada, the USA, and the UK hold Dr. Bondar’s fine art photographic prints. She is the author of several best-selling books featuring her writing and photography.

Above Lake Superior, the fathomless, starry skies that shift into daytime canopies of endless oceans of blue and sailing clouds, lifted my childhood imagination into adventures of flight. Early on, I observed that birds not only sounded and looked beautiful, they could also fly. I needed an airplane. Later, as an astronaut, I flew in space like a bird, without a passport across international boundaries. Truth be told, it’s not quite the same thing. Bird flight is gracious, flexible, reactive, committed, balanced, and purposeful to name a few qualities of the many. An astronaut floating inside a spacecraft may move purposefully, and although committed, is not nearly as gifted with flight, especially given a bird’s great ability to defy gravity on Earth, with sudden course changes, and prolonged flight without a foothold.

Space flight however, deepened the connection of my astronaut self to birds of Earth in unexpected ways. When in space in low earth orbit, not seeing birds or other life with the unaided eye (except for the Great Barrier Reef) contributes to the mystery of what lies beyond a spacecraft on the surface of a nearby planet. Not hearing bird sound or song is a chilling glimpse into a future where human impact and changes in climate will affect habitats, and survival of biodiversity—where birds might no longer be part of the natural life-support system of planet Earth. The purpose of this book is to share a visual story of two extraordinary avian species, one from each side of the globe, through the three perspectives of space, from the air, and from the surface. The premise is that if you love something, you will want to protect it. Space for Birds is one way of sharing an emotional reveal, of birds whose great flights to secure their future, teach us about respect for habitats and inhabitants of planet Earth.

As an astronaut, biologist, physician and photographer, my view of Earth is a blend of my personal view, and the prescriptive, professional astronaut’s view. I believe that we share a desire, however, that spaceflight will bring us more humanity, deeper insight into questions about life itself, and the universe–to see the world with greater clarity and compassion.

And that’s where bird migration comes into this story, for what birds see, touch and need, parallel our own lives. Birds pull us into places and patterns unexplored, habitat needs, superhuman feats, fragility, and resilience. Birds give us direction that is dynamic and not static, across the planet, from pole to pole and hemisphere to hemisphere. The vast distances covered by migratory birds traverse flyways that are transparent on earth ’s surface, skies and maps. With stronger understanding of distances, boundaries and edges of the habitat required by migratory birds, we can offer better protection to reduce biodiversity loss.

Killeen, Texas, south to Aransas NWR on the Gulf of Mexico, 2017.08.18, GMT 16:06:11. Photo credit: ESRS, NASA Johnson Space Center, ISS052-E-63066

The extent of these pathways in the air is emphasized by the space view as we are unable to capture an entire migratory corridor in one image. While space views are beyond the realm of most human experiences, the opportunity to see Earth from space is rewarded by visuals of unique and novel patterns of land and water. The camera angle and lens choice frame the perspective. A wide angle lens for example, allows scanning, and appreciation of distance. My bias is to ask that images from the International Space Station include ones at an oblique angle, with the edge of the Earth or limb, to remind us that we and all Earth’s lifeforms live on a planet.

West Asian/East African Flyway, looking northward from South Africa, 2016.04.03, GMT 11:51:33. Photo credit: ESRS, NASA Johnson Space Center, ISS047-E-44560

Aerial images grant us a different view of the relationships of water-land boundaries, which from the surface of Earth viewed across the landscape, are flat and almost two dimensional. Although avian vision is not identical to human vision, dissimilarities and discontinuities in the landscape would be recognizable by both bird and human being.

A solo Whooping Crane approaches a distant point, Wood Buffalo National Park, Northwest Territories/Alberta, Canada. Copyright Roberta L Bondar 2018

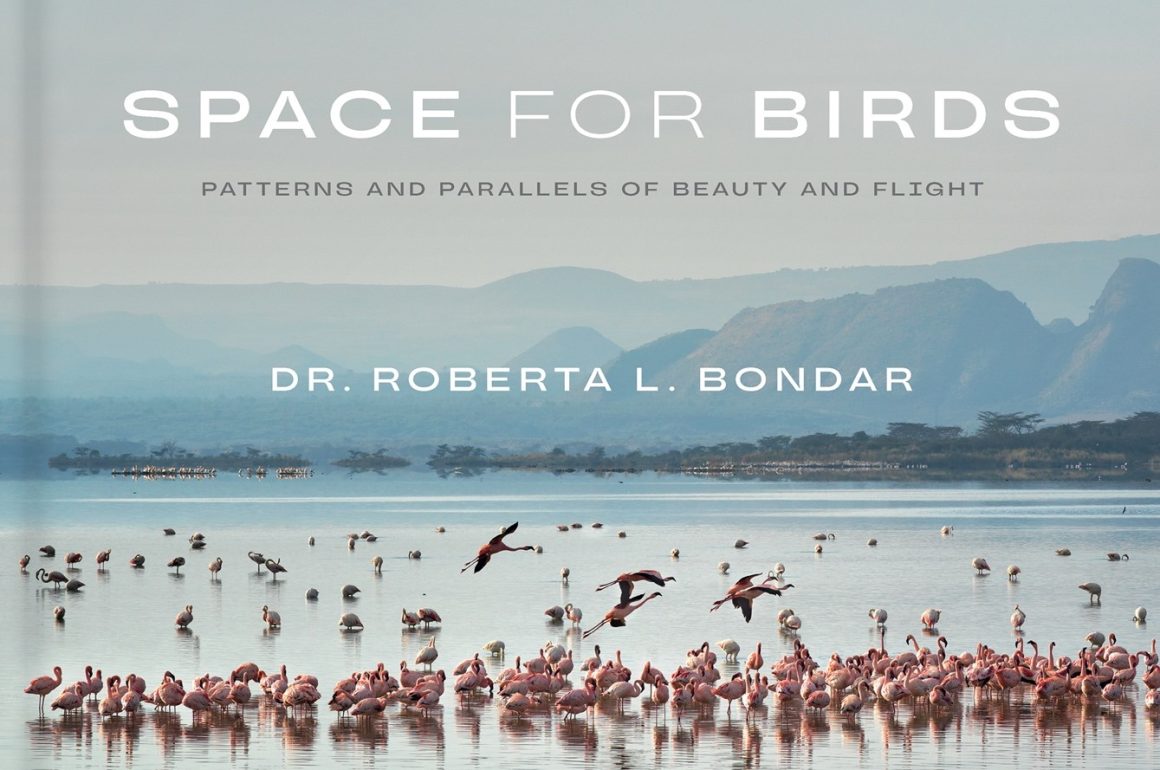

Space for Birds transports the reader along a path of discovery through images, supported by conversation, current scientific understanding, and discussion of artistic elements. It features the endangered Whooping Crane (Grus americana) of the Western hemisphere and the near-threatened Lesser Flamingo (Phoeniconaias minor) of the Eastern hemisphere. These two avian species are worlds apart in most behaviours yet share the same globe and vulnerability of habitat challenges.

An adult Lesser Flamingo preens, Lake Bogoria National Reserve, Lake Bogoria, Kenya. Copyright Roberta L Bondar 2018

A banded Whooping Crane displays its black flight feathers alongside its colt, Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, Texas, USA. Copyright Roberta L Bondar 2019

Whereas the white Whooping Crane tends to be solitary in pairs with its newly hatched young, the pink Lesser Flamingo is an example of flock behavior, where meeting, nesting, feeding, and flying are performed in groups that can be well into the thousands of individuals. Nesting Whooping Crane pairs may be separated by 20 to 50 km. Lesser Flamingos are colony breeders, all for one and one for all. Although both Whooping Cranes and Lesser Flamingos lay one to two eggs each, Whooping Cranes optimally lay eggs yearly after maturity, while for Lesser Flamingos, it is every five to seven years.

Lesser Flamingos in flight. Lake Bogoria National Reserve, Lake Bogoria, Kenya. Copyright Roberta L Bondar 2018

Way before I was born, Leonardo da Vinci created works that incorporated elements of what now are separated into cultures of either art or science. Trained as a neuro-ophthalmologist, I define my subspecialty as “how to see and view the world around us”, implying both art and science that my photography and writing reflect. For example, my goal is to share an emotional connection to the natural world of Earth, by stimulating entry into a frame that is artistically composed to intrigue the human brain. Once inside, curiosity to ask questions, no matter the depth of inquiry, will find answers in science. The greater the connection, the more prolonged the engagement and less fleeting its impact. Space for Birds uses retro views or canvasses of landscapes of light and texture onto which birds enter and leave on a timescale that is different from their backdrop, or indeed, from the planet itself as seen from space.

Space for Birds: Patterns and Parallels of Beauty and Flight by Dr. Roberta L. Bondar (Figure 1 Publishing) Available September 17th at bookstores everywhere

Leave a Comment