Josh Davis is a gay science writer for the Natural History Museum in London. For the past six years or so he has been writing about the amazing science and research going on in this world. Starting out studying Biology at University College London, and then spending over a year following gorillas around rainforests in central Africa, he couldn’t imagine that ten years later he’d work at the Natural History Museum.

We’re used to thinking about sex as being a binary of either male or female. But some species show that this is not a hard and fast rule and that occasionally animals can have more or fewer sexes.

The white-throated sparrow, for example, may be a familiar sight in the gardens and woodlands of across much of North America, but they are an extraordinary example of how nature questions our assumptions about sex.

One of the most intriguing things about the ubiquitous sparrow is that it comes in two colour morphs. Half the population have a black head with a white stripe running down the middle, while the other half have a brown head with a tan-coloured stripe. But the differences are not just in the physical, with the two colour morphs also behaving differently. The result is that males with a white stripe will (usually) only mate with female tan stripes, and females with a white stripe (usually) only with males with a tan stripe.

White-throated Sparrow

This means that, at any one point in time, any individual can only mate with a quarter of the population. This is – to say the least – unusual and so biologists were keen to figure out what was going on here.

By delving into their genetics, they discovered that the appearance and behaviour of the birds were controlled by a section of DNA that in half the population had been reversed. This process, known more technically as a ‘chromosomal inversion’, is thought to be exactly how the male sex chromosome evolved. The biologists therefore concluded that the birds were effectively evolving a second set of sex chromosomes, meaning that they were splitting into four sexes.

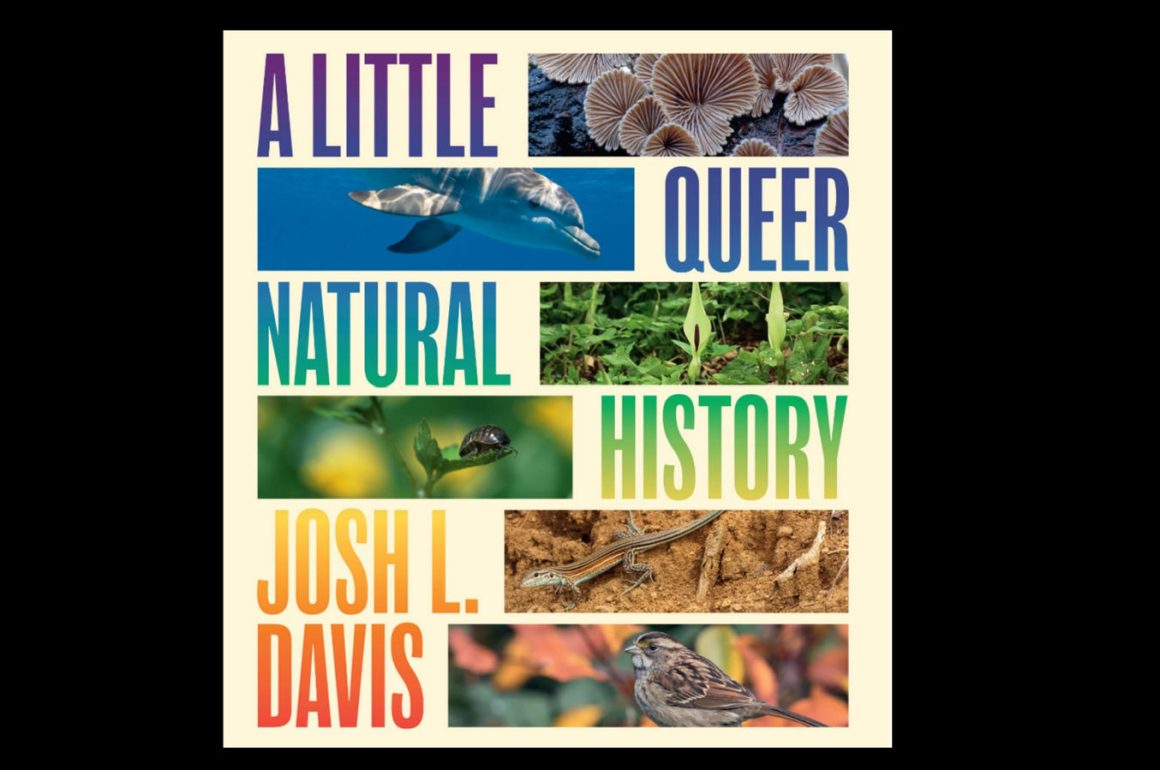

One thing I wanted to show with A Little Queer Natural History was that it isn’t just obscure or rare species displaying these behaviours or biologies. If you take a moment to explore nature wherever you are, there will inevitably be examples of queer natural history.

The book actually has its origins back in 2019, when I helped to co-produce and lead the Natural History Museum, London’s first-ever LGBTQ+ natural history tours.

Using specimens on display in the museum, we explored the myriad ways in which the natural world expresses a huge range of queer behaviours and biologies – defined as those which are not based on the heteronormative and traditional roles of one male and one female. This included species like parrotfish which change sex to penguins which engage in plenty of gay behaviour, and how those studying these species would often cover up, disparage, or explain them away.

Adélie Penguin

This research formed the basis of the book, which was expanded to cover a wider range of extraordinary behaviours found across plants, fungi and animals. The goal was to create an overview for people interested in queer natural history, giving individual examples of, for example, species which display parthenogenesis and an easy-to-understand explanation of how this works. From here I hope people can then go on to explore these topics further, rather than creating an exhaustive resource that lists them all.

One frequent assumption I kept finding was that when researchers see two individuals engaging in sexual behaviour they often presume they’re male and female. This has often resulted in homosexuality within the natural world going underreported. This is particularly true within seabirds, in which there is frequently only subtle sexual dimorphism.

In the 1970s the discovery of what were then termed “lesbian seagulls” caused something of a stir among the conservative and religious right in the US. It turned out that on Santa Barbara Island off the coast of California, up to 15% of all the nesting western gulls were female-female pairs.

Western Gull

At the time, the discovery of the queer gulls were probably the first time that much of the public had learned about homosexuality in the natural world. Since then, many other species of seabirds have been found to display similar behaviour. And while for most of the time, people now respond to discussions about queer nature in a positive manner (including in relation to this book!), there are still a vocal minority who will suggest that it is “not science” or “woke”.

I’m sure it doesn’t need pointing out that if same-sex behaviour is “not science” then what does that mean for opposite-sex behaviour too?

While attitudes towards queer animals may have improved in recent times, there are still stumbling blocks. A recent study found that whilst 77% of mammalogists questioned had witnessed same-sex behaviour in their study species, only 19% had actually published on it. The reasons for this may be different (it seems likely there are biases around journals not publishing as many short anecdotal data these days), the outcome is the same. A less rich picture of the natural world, and a failure to understand its full diversity.

I hope this book will help to open up some conversations around this topic, question the biases around these behaviours held within us whether implicit or explicit, and just celebrate the amazing kaleidoscopic world in which we live.

The natural world is incredible and endlessly diverse, and that is what makes it so exciting.

The book is published by UChicago Press – details at https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/L/bo236997883.html.

Photo Credits: Adelie penguins: ©T.Terziev/Shutterstock, White-throated sparrow: ©Glenn Bartley/BIA/Minden/naturepl.com, Western gull: ©M Rose/Shutterstock

I had the honour to review this book after a sneak preview and yes, I have never looked at white-throated sparrow the same since… I must say, in hindsight, Josh’ comments in this post make me question how my review may have come across. I wholeheartedly agree with Josh’ position.

There’s no morality in nature – so I do question those who’d deny the scientific nature of facts as we find them. Suppressing significant findings because they contradict an existing world view is very unscientific indeed and it impoverishes us all.