To say that an update of John MacKinnon’s “A Field Guide to the Birds of China” (2000) has been highly anticipated by birders interested in Chinese birds is almost an understatement. While there are some decent Chinese-language guides, they are of limited use for (local) illiterates like me. The 2000 MacKinnon guide is showing its age while my preferred choice for the Shanghai area, Mark Brazil’s “Birds of East Asia”, covers non-Chinese locations such as Japan and Korea while excluding Western China.

Maybe the level of anticipation was too high – in any case, the new guide turns out to be rather a disappointment.

But let us start with a few positive aspects. The book has a reasonable size and can be carried around in the field. There is also a far cheaper, even more portable electronic edition. The book has bird names in English, Latin, Chinese, and Pinyin – very useful for somebody like me to communicate with local birders. There are QR codes for vocalizations taken from Xenocanto – also a very useful addition.

The book covers all of China, which given the large number of species (1484 are covered in the guide), the relatively low level of bird knowledge and also the limited market for such a book in English language (MacKinnon claims in one interview that the Chinese edition sold ten times more than the English one) is quite an achievement.

As for the font size, what Dragan said in his recent review of the Lynx Malaysia guide also applies here (and I wish I had come up with it): “The font size may be small, yet that is already the standard in field guides so I gave up complaining but started to wear glasses”.

But then, the negatives. Mind you, I am not a particularly good birder – I am the kind of birder who really needs a good bird guide. So, the points below may not really be highly relevant. Also, I am not qualified to discuss the extent that the guide is up-to-date with the current ornithological literature (if it was up to me, I would probably declare the existence of subspecies as illegal). But the fact that I detected a number of flaws in the guide give me the nagging feeling that there may be many more lurking in the many species descriptions that I cannot comment on at all.

Actually, the book arrived at my home while I was out at Nanhui, a place that is even briefly referred to in the introduction of the book – “the underprotected reedbeds of Nanhui Cape”. At Nanhui, I saw a few Common Moorhens along with some other, duller-looking but similarly-shaped birds. Now I know from previous disappointments that these will very likely not be the hoped-for rare rail or crake species but rather the immature moorhen, but to be sure, I decided to look the bird up in my new guide. It turns out that the immature plumage of the Common Moorhen is not shown in the MacKinnon guide despite (in my opinion) being sufficiently distinct.

Adult Common Moorhen: Plumage shown in the “Guide to the Birds of China”

Juvenile Common Moorhen: No room in Mr. MacKinnon’s house

Next, I looked up the illustration for Chinese Grey Shrike and compared it with the one in the Brazil guide (Birds of East Asia). It seems to me that the latter is more detailed, simply better. Many of the illustrations in the MacKinnon guide are a bit vague, and the colors are a bit dull. It is kind of hard to make a Red-billed Leiothrix a slightly dull-looking bird, but somehow the guide manages this feat. Many of the illustration pages give the impression of having been out in the sunshine for too long. Of course, I cannot rule out that this is an issue with my specific copy, though as I paid for it myself, this would not be such a great thing either.

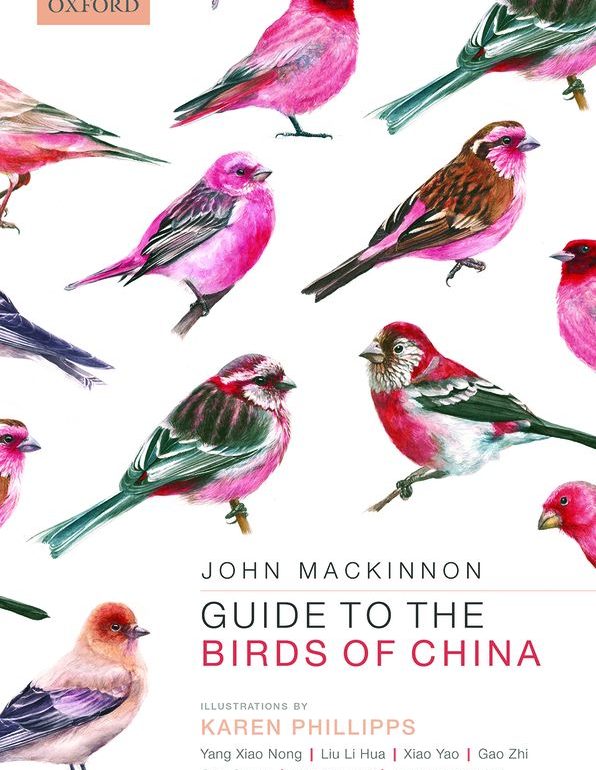

I am wondering whether the somewhat underwhelming illustrations are partly due to the fact that the main illustrator who contributed more than 1000 illustrations, Karen Phillipps, already died in February 2020. In fact, many of the illustrations seem to have been taken from the 2000 edition without substantial changes. For example, the plate on cranes seems to be completely unchanged from the 2000 edition, which means that compared to the Brazil guide, there is again no separate illustration for the juvenile Common Crane.

Accurate illustrations should be particularly important for this guide as the species descriptions are clearly on the short side (“concise”, as the cover blurb calls them). To give an example, while the visual description of the Chinese Penduline Tit covers more than 300 words in the HBW, MacKinnon manages with about 45 words (Brazil uses about 75 words).

On the other hand, some of the information provided seems almost too generous. For example, about half of the shortish entry on the Azure-Winged Magpie discusses subspecies, particularly their geographic distribution. Given that there is only one illustration and no information on the actual difference between subspecies, this seems rather pointless. For this particular species, it is also not quite clear how it helps with the identification to add a specific marker “blue on wings” to the illustration, as this is hardly an aspect even a casual birder is likely to miss.

It must be a hell of a job to prepare distribution maps for the almost 1500 species covered in the guide. On the other hand, in some way the task is simple – just look at eBird. For some reason, this is not the approach that has been consistently taken in this guide. I have never seen a Greater Coucal in Shanghai, and both the HBW and eBird locate its range further south. And yet, the distribution map of this species in the MacKinnon suggests I should have a chance of finding a Greater Coucal here.

Taking a page or two from Donna’s typical reviews, a few notes on usability. Coming back to the Chinese Grey Shrike, the poor bird gets assigned three different numbers – it is species number 680 on page 234 and shown on plate 81. The index actually only shows species and plate numbers, not page numbers. I have to say, I find this bewildering (to be fair, I have already wasted several hours of my life looking up the wrong page in the Brazil guide, as it also mixes plate numbers and page numbers). There is a reason books only have one ISBN number, not three (ok, admittedly you might argue that they have two, an ISBN-13 and an ISBN-10, but you get my point).

Another puzzling formatting choice is that there frequently are double pages of text followed by double pages of illustrations. These may not even match directly. For example, page 368/369 has the description of 10 species of parrotbills while the next double page shows the drawings of 19 species of parrotbills. I have read my share of bird guide reviews in the past, and I cannot remember this ever not getting criticized.

I would have liked to add some example pages to this review – however, wanting to do this properly (I am German, after all), I asked Oxford University Press for permission to use some sample pages of their choosing. Instead, they referred me to an agency that apparently handles these inquiries – but the search engine of said agency neither knows of the existence of an author named MacKinnon nor the ISBN number of his recent book. Another follow-up with the publisher eventually brought the advice that I should check with the author which illustrations could be used – I had kind of given up by then. Making sample pages hard to obtain may not be an ideal marketing strategy.

There are some sample pages on the NHBS website – you can see them here – I cannot tell whether they got official permission to use these though (from the way the content close to the middle of the book looks warped, it seems that these are scans rather than taken from a pdf file). The official announcement of the book on the publisher’s website also does not have any sample pages apart from the book cover and a non-working link to something called Google Preview. It almost seems as if the publisher is not too confident about the illustrations himself.

Don’t get me wrong – for foreign birders visiting China, this is still a guide worth buying, particularly given the lack of English-language alternatives – it is simply the only guide to cover all of China. However, it is a guide that could have been so much better, given the high quality of some recent bird guides such as those published for neighboring countries by Lynx Edicions. In retrospect, it was probably a mistake to use the 2000 guide as a basis for the new guide, as this prevented the adaptation of many of the changes and improvements that have become standard in these last two decades.

Finally, on a personal note, I strangely feel slightly guilty about writing this less-than-stellar review given the undoubted merits MacKinnon gained with his 2000 guide. But overall, it is undeniable that I will keep using the 2009 Brazil guide as the standard reference for birding in Shanghai, rather than this new guide.

Additional reading: An interview with John MacKinnon (by Craig Brelsford) on the release of the guide is available on Shanghaibirding. Another one covering the same topic by Han Xuesong is on Birdingbeijing. Both sites also offer a way to get the guide at a discount.

Guide to the Birds of China

by John MacKinnon (Author), Karen Phillipps (Illustrator), Yang Xiao Nong (Illustrator)

Publisher OUP Oxford, 2021

ISBN 978-0192893666 Hardback

Length 560 pages

Dimensions 16.2 x 3 x 24 cm

Weight 956 g

Official US release date: April 22, 2022 (the UK edition has already been released)

For distribution maps, I doubt that we can just “look at ebird”. How many Chinese birders you know use ebird? Take the Greater Coucal example, there is literally zero report of Greater Coucal in Hunan Province (as of 2020-03-20) on ebird. But on birdreport.cn there are hundreds of reports of Greater Coucal in Hunan in recent years.

Shanghai is generally very well watched by primarily Chinese birders, and no Greater Coucal are reported by them on eBird, nor have I ever seen one. I doubt very much checking this species on birdreport.cn will give you a different result. I cannot speak about the situation in Hunan.

I just checked on birereport.cn. There were reports of Greater Coucal in Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Hubei, and of course Hunan in recent years. These are all provinces north to the distribution range on BoW (birds of the world) or ebird. But yeah, since you are in Shanghai I think you are probably right about the popularity of ebird among Shanghai birders.

Anyway, my point is that ebird and birdreport can be complementary when it comes to China. It would not hurt to check on both sites instead of just one of them.

As with this guide, maybe the author(s) of this it used observation data from multiple sources (i.e., not only from ebird) and gave us distribution maps different from those on BoW or ebird.

Thanks for your reply Kai! I actually just checked on birereport.cn. There were reports of Greater Coucal in Shanghai, Jiangsu, Hubei, and of course Hunan in the recent six years. These are all provinces north to the distribution range on BoW (birds of the world) or ebird. But yes, since you are in Shanghai I think you are probably right about the popularity of ebird among Shanghai birders.

Anyway, my point is that ebird and birdreport can be complementary when it comes to China. It would not hurt to check on both sites instead of just one of them.

As with this guide, maybe the author(s) of this it used observation data from multiple sources (i.e., not only from ebird) and gave us distribution maps slightly different from those on BoW or ebird.

Sorry about my repeated comments. I removed Zhejiang in my previous comment, because I found it is actually in the BoW distribution range. And thank you for the detailed review Kai! For birders in Shanghai, I agree there are good alternatives. For birders not in Shanghai, like myself, I feel this is a guide I must check.

P.S. I just ordered the book and it is spring now! I can’t wait to take this guide with me and do a lot of birding!

Hi! After using this guide for several weeks, I am back and would like to talk about my experience with it.

Let me start with the negative things.

(1) Like Kai said in his review, I feel the quality of illustrations is not consistent across the book. The reason is simple (I guess), many illustrators, besides the late Karen Phillipps, have contributed to this guide. Some illustrtions seems to be taken from the old 2000 guide. But some new illustrations are fine and full of details. I hope in the future versions of the guide the art style and quality of illustrations can be better and more consistent.

(2) I also wish there could be more illustrations for species that need to be highlighted (see the Common Moorhen example in Kai’s review).

(3) Also, the paper of the guide (I’m using the north American version) is not as good as other field guides I have (e.g., the national geographic field guide). It’s a bit shame that the Oxford University Press didn’t use better paper, considering this guide is more expensive than the others.

(4) The index only shows bird number and plate number, which Kai found annoying. But I guess the author has to do so, because the book doesn’t use the usual “left text – right illustration” style. Some times there are several consecutive pages of text and then followed by two pages of illustrations. If they also include the page number in the index, then a species would have four numbers – bird number, plate number, page number for text and map, page number for illustration. I actually find myself OK with the index, but I’m still not used to the text and illustration arrangement.

(5) I really wish the book can have the “left text – right illustration” style like most field guides. My guess is that the current style allows the author (or publisher) to minimize the size of the book. With almost 1.5K bird species to cover, saving 1 page for every 30 species means a total saving of 50 pages. This can help reduce the weight on the hands of the reader, as well as the cost of the publisher and the price of the guide.

With all those points I put above, I still LOVE this guide. As Kai said in his review, ” it is simply the only guide to cover all of China”. I love that it covers almost 1.5k species. I love that it has lines pointing to places I need to pay attention when IDing a bird. I love that it includes QR codes linking to xeno-canto. I love that it has updated taxonomy and distribution maps.

Oh, by the way, the distribution map problem raised by Kai in his review is actually answered by the author. It turns out that the author did not only rely on eBird maps but used some Chinese domestic data. In the last paragraph of Acknowledgements, the author wrote: “The work is strengthened by access to many global resources such as photographic images, maps, sound libraries, eBird maps, Handbook of Birds of the World information, and published articles. I have benefitted from access to several Chinese domestic resources not widely availed by international bird watchers such as the magnificent photo posts on Birdnet and other platforms, taxonomic updates by Chinese Bird Record (CBR), and access to the location records mapped for all species by CBR members.”

P.S. I found there are several mistakes in the book that are the same as the Chinese version. There is an online discussion about the mistakes in Chinese version on Douban. The link is https://book.douban.com/review/14246790/

Ich war so enttäuscht darüber das das alle “alten” wirklich nicht mehr zeitgemäßen Zeichnungen von K. Pphillips übernommen wurden ,die einfach nicht mehr den neuen Vogelführern die NEU auf den Markt kommen Paroli bietet.

Einige neue Seiten die wirklich neustem Standard sehr natürlich und hochklassig Vögel abbilden und entsprechen,machen leider nicht einen Gewinn an Anschauung und GENUSS aus sich die Abbildungen zu betrachten.Also als Fazit “Alter Wein in neuen Schläuchen”

Ich habe das Buch sofort zurück geschickt und Benutze das “alte ” weiter.Ich hatte mich so gefreut ….SCHADE!!