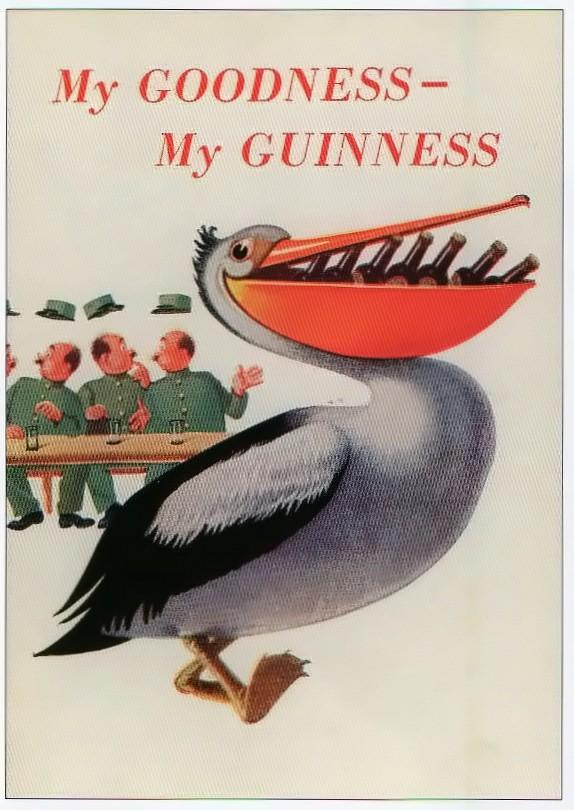

Yes, I know: I went out of my way to avoid the predictable Guinness review before Saint Patrick’s Day last week. But while that holiday has come and gone, 2018 remains the bicentennial year of the first export of Guinness to the United States, an anniversary the brewery is commemorating with a special release of Guinness Draught in cans decorated with its famous Guinness “Zoo” advertising art from the 1930s. Anyone who has set foot in an Irish pub at any point in the last several decades has undoubtedly seen these vintage ads featuring a colorful and clownish menagerie of bears, sea lions, turtles, kangaroos, crocodiles, lions, and many birds – including the famous Guinness toucans. Even with Saint Patrick’s Day just past, the reappearance of these whimsical toucans on cans of Guinness is all the excuse I needed to feature this special release on Birds and Booze.

So how did the colorful, tropical toucan become the quirky and unlikely mascot of Guinness, not only one of the most famous beers in history, but a quintessential icon of Irish culture worldwide? In 1935, the brewery was concerned about declining sales and hired the London advertising firm of S.H. Benson to do something about it. Ironically, the Guinness explicitly wanted to avoid a campaign that focused too strongly on their sole product – beer. John Gilroy, the S.H. Benson artist and illustrator responsible for the iconic Guinness artwork, explained the company’s peculiar request:

“The Guinness family did not want an advertising campaign that equated with beer. They thought it would be vulgar. They also wanted to stress the brew’s strength and goodness. Somehow it led to animals.”

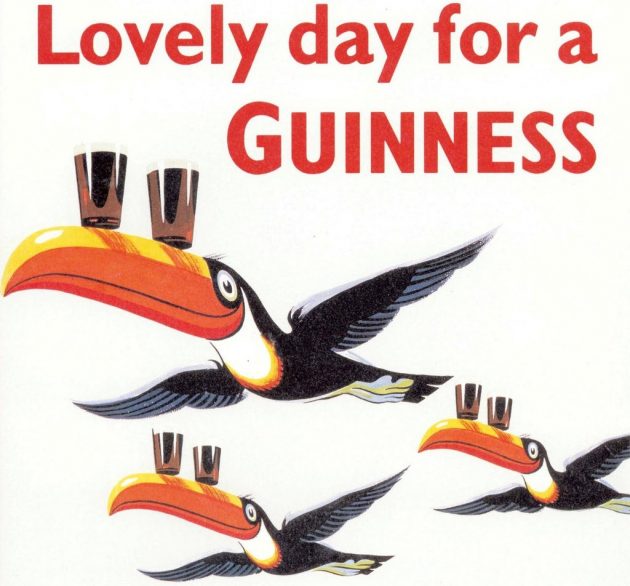

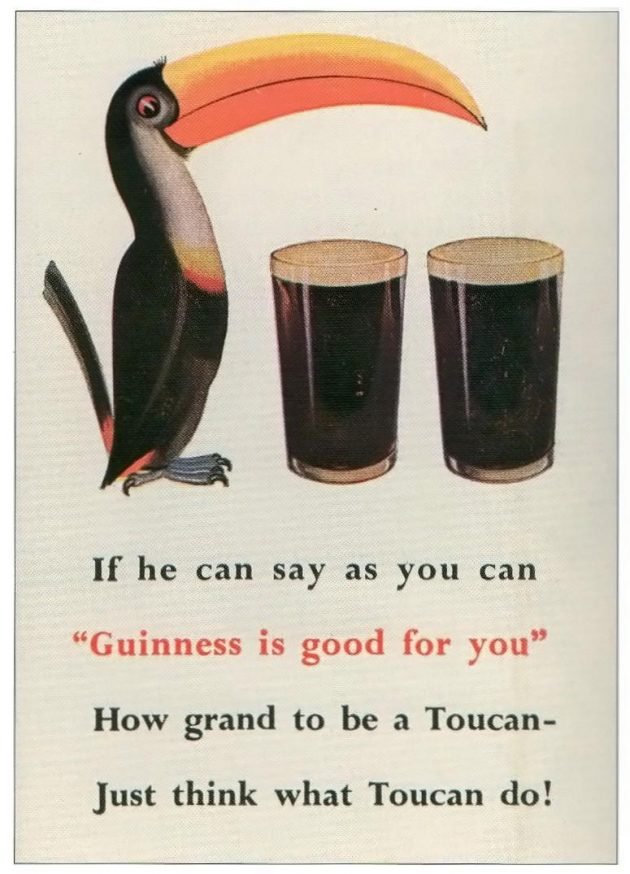

S.H. Benson struggled to depict a suitably representative human household to market the wholesome family image desired by Guinness, until Gilroy made an inspired and unlikely flight of fancy to the toucan family Ramphastidae. It worked, and the campaign took off – quite literally – featuring amusing squadrons of toucans in flying formation, with weighty pints of stout balanced on their large, colorful beaks. Some have also pointed out the striking visual symmetry of the black and white plumage of the Guinness toucans mirroring the colors of the stout, with a bit of sunny, tropical orange thrown in for good measure.

Tropical birds delivering Irish beer: Guinness has long been a popular export to tropical markets, even inspiring homegrown stout brewing in the Caribbean and elsewhere. Remember that the next time someone suggests that dark beers are strictly for cold-weather drinking.

Working with Gilroy on this assignment was copywriter Dorothy Sayers, who gained later fame as one of England’s greatest crime fiction writers, and for – fittingly enough – coining the maxim “It pays to advertise!” Sayers perfectly paired Gilroy’s playful illustrations with an amusing series of quaint, punny doggerel and whimsical slogans, which have become an equally inseparable part of Guinness lore.

Of course, Irish dry stout isn’t just a beer for Saint Patrick’s Day, but it isn’t given as much respect as it deserves in craft brewing circles these days. Notwithstanding the immense international success of Guinness, the lighter Irish style suffers somewhat in uninformed judgment alongside the big and bombastic stouts of latter-day American craft brewing. Guinness dominates the traditional market, though Beamish and Murphy’s produce equally worthy expressions, and American craft brewers seem reluctant to try their hand at the style (though I can recall enjoying versions by Brooklyn Brewery and others). For the time being, Irish dry stout remains one of the world’s popular beer styles that hasn’t been done to death by American craft brewers. Their reluctance to tackle the style can be blamed in part on the daunting shadow cast by Guinness itself, but also on the unassuming and uncompromising simplicity of Flann O’Brien’s “pint of plain”. Guinness and other dry stouts are modest yet clever affairs that make the most of a humble list of ingredients, offering little room for the brash imposition of American hop varieties, coffee, cacao nibs, barrel-aging, and other ploys of modern stout brewing. For better or worse, the well-defined archetype established by Guinness will only tolerate so much departure from tradition. I also suspect that blasé craft beer drinkers underappreciate its subtle value as a reliable, everyday drink, lacking as it is in novel, exciting ingredients, hangover-inducing levels of alcohol, or blistering hop additions.

Guinness calls the stout it exports to American markets in cans “Guinness Draught”, a paradox based on the inclusion of a nitrogen gas “widget” in each can that produces a fine, creamy head when opened and poured, a device intended to simulate the famously slow, hand-pumped draught found in traditional pubs. Beneath this soft and rich mousse lies “the black stuff”, the impenetrably dark liquor produced by infusions of deeply roasted barley that define the Irish dry stout style. Guinness exhibits a surprising dusting of earthy hop aroma, but the flavor is dry and roasted, nearly burnt, with gentle hints of licorice, dark and fruity toffee, and an underlying bitterness. A silken, creamy mouthfeel rounds out the assertive parts that make up the whole of this consummate Irish stout. Altogether, a perfectly pleasing and comfortably familiar pint, but it could stand a bit more sour tang to counterbalance the considerable creaminess, and to accent the roasted character. That’s quibbling about a undeniable classic, but the ongoing quality of Guinness in its many incarnations and formulations over the years is an never-ending source of debate.

Being a bit old fashioned, I find it refreshing that Guinness abstains from the perennial, often desperate, and usually obnoxious attempts of other international breweries to launch inescapable, viral marketing schemes, replete with buzzy and immediately-dated catchphrases (hey there, Budweiser!), preferring instead to rely on the simple but effective stable of classic advertising produced by Gilroy and Sayers over 80 years ago (not to mention the even older Guinness Harp). Given that, I suspect the company is in no great rush to replace such enduring artwork, and it’s always a treat to see them resurrect these timeless images. But as the holders of a legendary 9,000-year lease on their brewery at Dublin’s St. James’s Gate, Guinness has plenty of time to come up with even more fanciful avian advertising in the centuries to come. I’d like to predict that someday these will be featured in Birds and Booze reviews of the distant future, long after I’m gone. But I do hope they remember to bring back the toucans once in a while.

Good birding and happy drinking!

And now for something completely different…

____________________________________________________________________

Guinness Brewery: Guinness Draught

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Three out of five feathers (Good*)

*A definite classic: debatably not what it once was or still remains in certain settings, but still enjoyable.

Leave a Comment