It’s a common call/email/text that most bird watchers get this time of year:

“HELP! I just saved a baby bird! What do I do? What do I feed it?”

My typical answer is, “Put it back where you found it because you most likely found a fledgling learning to fly and it needs to be back in the wild to finish flight school,” which I find to be a very unpopular answer.

If it is an emergency and since I get calls and texts from all over the country (even a few out of the country), I direct people to Rehabber Search or Wildlife Rehabber. Both of those sites allow you to enter your zip code or state and find someone nearby who has the state and federal permits that allows them to treat wild birds.

However, let’s take a moment to figure out if the type of baby bird you found truly does need help. The general rule is that if it has feathers, it can fly and leave it be. But maybe this will help you triage the situation when you see a baby bird:

This is a very young House Wren. You typically do not find a bird this naked or featherless outside of the nest unless there has been a storm or the nest has been attacked by predator like a raccoon, chipmunk, squirrel or corvids. If you happen to find a baby bird this featherless, take a moment–is there a bird nearby chirping at you angrily? That is probably one of the adults. See if you can find a nearby nest, if you can reach it easily place the chick back into it. If it’s after a storm, try gathering nesting material and place it in a dish up off the ground. A Cool Whip container works well (punch some drainage holes below it) and the adults might still care for it. Keep in mind that if you stand out in the open and watch, the adult birds are going to think it’s a trap and ignore the chick.

If the nest was in a bird house, open the house and check the damage. You may be able to repair it and the adults will finish rearing the chicks. Do not worry about touching the baby birds. The adults of most species will still care for the chicks no matter how much you touch them. That’s an old wives’ tale that says bird won’t take care of a baby bird with a human smell on it–not true at all.

If you cannot find the nest or it’s too destroyed, do not try and raise a chick this young. It’s easy to choke it with food while you’re feeding it and chances are good that you’d raise the chick like a pet and you’d end up with an adult bird that doesn’t know what its predators are and seek humans for food and mating…aka an unreleasable bird. It’s illegal to raise wild birds (even orphaned ones) without state and federal permits. Use the wildlife rahbber links at the top of this page to find a licensed pro near you.

This young American Robin may look gangly but it’s supposed to be out of the nest, it’s fine. If you see a baby bird running around on the ground with this many feathers–it doesn’t need your help. This is the equivalent of a 15 year old with a learner’s permit. Believe it or not, most of the birds that nest in backyards are ready to leave it 13 – 15 days after hatching! They need another day or two to figure out how to use the flappy things on the sides of their body and yeah for a week they are going to be awkward in their movements and very vulnerable to predation (especially cats, keep them indoors) but this adults hang out and watch them. They give them warning calls, teaching them what is dangerous and when to hide. If a baby bird at this stage is taken to a rehabber, it’s waste of the rehabber’s time and the chicks will miss valuable training from their parents. Wildlife rehabbers are good, but what human can teach where to flip the best leaves to look for grubby larvae? What human can point out a fox hidden nearby and how to avoid it? Humans can fatten birds up and get them strong enough to fly, but we can’t teach them the really important stuff for bird survival.

Keep in mind that birds at this stage will flutter and look like it can’t fly very well, but it’s fine, it’s all part of the learning process. If it is in immediate danger from cats, try and shoo it away from the cat and lock the cat up indoors (preferably for good) or at least while the bird learns to fly.

Do not attempt to put a baby bird that is fully feathered like this back in the nest. Once they are old enough to flop out of the nest, they have no desire to stay there.

Young raptors like the above Bald Eagle chick are a different matter. They take a lot longer to grow and develop, unlike the two week growing process of most songbirds. If you find a young hawk or eagle out of the nest and it is covered in down and is unable to stand on its huge feet, it needs to get back in the nest. Many states have rehabbers who only do birds of prey. Many partner up with tree climbers who attempt to get the chicks back to the nest and under the care of the adults. Some even go as far as to rebuild the nest or make a platform beneath the nest and place the chick on that. When that isn’t possible, many raptor rehabbers keep tabs on nests and will place an abandon chick in a foster nest. Birds of prey look cool, but they can’t count. A female red-tail may leave a nest to hunt for her two chicks and return to feed a rabbit to three chicks without noting an increase in the number of chicks a rehabber has placed there.

Owls are a little different. They don’t build nests and some like Great Horned Owls take over old hawk or squirrel nests. They do no rennovations and the nests usually fall apart about midway through the season. Before baby owls (like the above Great Horned Owl chicks) are able to fly, they go through what is called a “brancher phase.” Their feet are already fully grown and very strong. If they blow out of the nest, they can usually climb their way up to a branch and the parents till tend to them. If you find a fluffy owl that looks similar to the bird in the above photo, it’s probably a brancher and the adults are waiting for you to leave to care for it. Leave it be. Feel free to contact a raptor rehabber, but they will guide you through questions about the brancher phase. Remember that owls are masters at hiding, you may not see the adults, but they see you and they won’t go near the chick while you are there…even if you’re hiding behind a tree. They have excellent hearing, they know you’re still there.

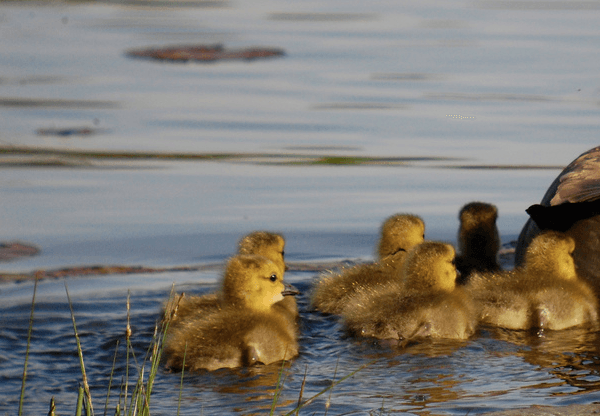

Young waterfowl are their own weird set of problems. Above are Canada Goose goslings. The first few years for female ducks and geese are kind of practice rounds. They need to learn by trial and error (often deadly to the chicks) where to safely place the nest, how to keep young in a tight group and hide them to avoid predators. Sometimes females have eggs to lay but no nest and the eggs can end up anywhere from other duck and goose nests…there was even a case in Minnesota where a Canada Goose laid an egg in an Osprey nest and the raptors incubated and hatched it!

The best bet for a lone duckling or gosling is to hook up with another brood of chicks. Experienced Canada geese will corral young from less experienced females and you’ll find rafts of 20 goslings tended by a four adults–safety in large numbers. A lone gosling or duckling is vulnerable to all sorts of predators like raptors, bass, herons, fox, snapping turtles and foxes (just to name a few). Try to get it too another family group or contact a wildlife rehabber. Some rehabbers even have surrogate ducks or geese that they can raise a lone chick with and teach it to survive. Never raise a wild goose or duckling yourself. Some feed stores try to sell the ducklings as educational projects for kids over the summer. The thinking is that in late summer when the ducklings are adults, they can be released in the wild. Granted, it’s fun for kids to raise some ducks but keep in mind, no one teaches these ducks what their predators are and most succumb to fox and coyote attacks within a week of being released as adults. Also, the ducks have associated humans as their flock and food and are very confused when dumped in a park.

At the end of the day, most of the baby birds dropped off to rehabbers do not need to be rescued. It’s hard to watch nature sometimes, it’s a bird eat bird world and when disaster strikes a nest, our love of birds often drives us to want to help them. Remember, that if it is an emergency go to Rehabber Search or Wildlife Rehabber and find a licensed pro wildlife rehabber to help you out.

Sharon, this is an incredibly valuable post. Thanks for sharing such timely and critical information illustrated by cute chicks!

Thanks, Mike. I know some people have a heard time understanding the question, “Is it fully feathered?”

I hope this helps people figure out when to help out baby birds.

Wonderful post!! Thanks so much for this information.

Thanks for the great post Sharon. Having an egg and nest identification service on my blog, I am always getting questions from people who really want to help the birds but are actually disrupting their natural breeding, nesting and learning process.

I always advise leaving eggs where they lie noting that a human cannot possibly give a baby bird what it needs to survive in the wild, much less raise a wild bird from an egg.

It’s also important that these well-meaning folks understand that it takes a professional wildlife rehabilitator to bring an immature bird from pre-flight status to a state in which that bird can live in the wild and survive.

Thank you for spelling out some much needed information for bird lovers all over the world as to the proper way to “help” birds found in the wild.

Thanks so much! This information has probably saved this little Birds life! I’m pretty sure now that i’ve read this that it will be fine, I just need to put it back and keep my dogs inside! Thanks again!

A CAT JUST CAUGHT BABY BIRD, IT LOOKS LIKE IT IS SILENTLY SCREAMING, DOES THAT MEAN IT WANTS FOOD ? IT IS SITTING WITH HIS HEAD UP BUT I HAVENT SEEN IT MOVE FEET OR WINGS, IS IT IN SHOCK ? HELP I CANT PUT IT OUTSIDE B/C THE NEIGHORHOOD CATS.

Ive tried to help a baby bird i tried to picked it up and put it back in the nest but i was unable to complete my mission because of the mom and dad birds they tried to attack me like i was going to eat their baby bird… the worst part is every time i walk out my house baby birds mom and dad scare the crap out of me .. they usually fly an arm length above my head and whistle and i usually panic and act like a ninja more like an idiot haha i fall for their tricks every time i wish those birds were already good to fly so maybe their mom wont try to kill me every time i walk outside.. its crazy they forced me to quit smoking so i bought a bag oh halls (true story) lol sorry for my english but im not american

what if the baby bird was found by someone else?

we have a baby bird that has down, but still has his eyes closed. we fed him mostly liquid mushed up dog food because someone said it has the nutrients the bird would need. we don’t know where the parents are. but we need to know how to care for it for a week or two. can you tell us?

Did you not search for a wildife rehabber near you? There are links and everything. It’s difficult to raise a songbird and most cases illegal. Most baby birds fledge two weeks after hatching.

Use the link and find a licensed professional.

A baby bird fell off an tree! And I ain’t know ow to climb 5 meters.????i was about to go swimning but it fell down

Well just give it to me! I will take care of ze baby bird!just feed it milk & cookies????

Thanks for info I now know what to do about Wren nest on my patio #1 keep cat inside witch is problematic but I watch her to make sure she leaves the area although i can not keep an eye on when she returns she usually is laying nearby then I bring her in

yes, it may be looking to be fed; but until you know what kind of bird it is, you won’t know what kind of food it eats. When there are no adults looking or other nestlings making noises out there, and hidden observation hears/sees none; I cover bases by feeding a fishbase cat food pate’ mixed with powderized dried mealworm. Does’n t’ hurt to keep it onhand, keeps forever. Is great add to chicken food or house bird food, and to birdfeeders. Look up your bird here/online to find out what it is. DO NO FORGET about the parents; they should be out there; keep LOOKING, listening!! Feeding that bird is an 18 hr day job every 10-15 minutes of the right stuff; but it is only food; you must try to find wild parents or find wild bird rescuers to help rehab it and restore it to the wild. You cannot do this!

good heart for trying to help a baby; hope you were able to put the baby in a safe place where parents could find it and continue to feed and lead it away to their teaching and feeding of the baby. They may be wondering where their baby is; hope you got it where they could find it. If they nest near your door again, hope you will avoid that door as much as possible, and not touch the baby if you see it during its fledgling stage, which is over a week for most birds, but they usually try to keep their baby in places where people and animals are not able to see it. They misjudged you, don’t let them down next time

Hi, I am looking for advice. Today is Saturday, and this morning my landlords cat brought a baby bird to us. I was able to save the little dude, without much injury. I do not know where he came from, and I washed a tiny wound closer to his backside from the cat’s tooth. He seems to be fine, and has taken a liking to hanging out with me. I have tried to call several local offices and wildlife rehabbers – to no avail. The local offices aren’t picking up the phones and I have left messages. Listings don’t show any aviary rehabbers, but I did call them anyway and leave messages with all the contacts I could collect. I am trying to identify the little guy so I can at least keep him alive until I can find a proper place to take him in for care. I need help doing this, and I am hoping that by making contact with someone who has more experience in this field, hence this message. He appears to be a fledgling, sprite little dude. Brown coloring, but his belly is more of a light tan. He has a row of coloring in his little wings that matches his belly. He h as some silly looking down feathers on his head, and sporadic spots on his body but nothing to give me the dominated in down. Perhaps he is still a nestling, but on the older side. He’s so tiny I thought he was a hummingbird at first. I have photos and video that I can send for reference. I just want to keep him alive until I can get him to hands that know how to care for him best. I hope to hear from you, and thanks for the consideration.