In honor of fall, and of the Chipping Sparrow that just smacked itself (thankfully not too hard) against my balcony window, here’s a blast from the past:

Oct. 2009

The morning is cold, and it’s damp, although not the buckets-from-the-sky affair that yesterday was. Dawn is getting later and later. The lawn seems bare of birds, except for a single female Flicker. Overhead, a white-tailed young Red-tailed Hawk calls. It’s my first return to Prospect Park since my overwhelming San Diego adventure and things seem quiet, despite favorable overnight winds and gushing reports of a wild sparrow bonanza the previous day.

Could I ever readjust to land? Could I go home again? Or was I, like so many birders, doomed to eternal restlessness, always investing somewhere else with the glamor of new birds and new experiences?

There’s a movement at the corner of my eye, and an off-leash dog bounds towards me (not an issue you have to deal with on pelagics much.) And as it does, scores of brown and yellow sparks fly up from the still-green lawn, each giving a high sharp note of alarm, and stream over my head to the nearest tree.

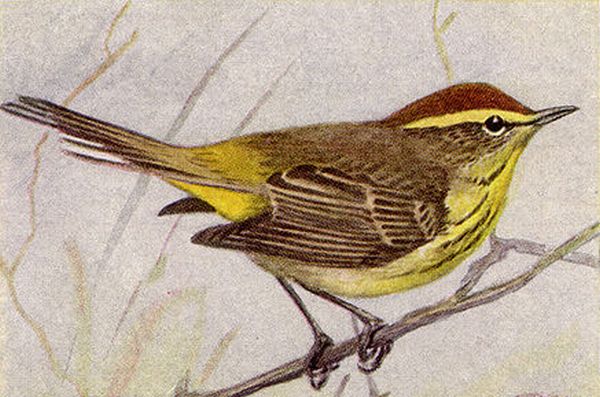

The Palm Warbler is so common that a lot of birders never stop to think just how odd they really are. Despite the name, they have more stomach for cold weather than many of their cousins; they migrate early in the spring, late in the fall, and nest in northern Canadian bogs and pines rather than in their namesake trees. Like the similarly hardy Yellow-rumped Warbler, the Palm pulls off its extended temperate sojourn by switching to fruits and seeds when cold knocks down most of the insects that make up their summer diet. (Interestingly, the Palm Warbler shares spur on the Dendroica family tree with the Yellow-rump – but also with the more traditional Black-throated Blue and the sun-loving, southern Yellow-throated Warbler.) But while the Yellow-rumped Warbler still tends to stick to the trees, the Palm Warbler throws wood-warbler-ness to the wind and gets down on the ground, often sharing seedy parkland and edge habitats with flocks of sparrows.

Like right now, for instance. Roughly half the brown sparks are warmed with reddish tones; Chipping Sparrows on their way to winter in Florida or even further south (or perhaps just waiting for Halloween to change into American Tree Sparrows and trick-or-treat us all into filling our feeders.) The other half glow more-or-less yellow. That more-or-less covers a vast range – both metaphorically and literally, as the yellower birds are eastern breeders and the more whitish ones hail from the west.

I watch the birds settle into the nearby shrubs and weeds, picking around for late bugs and grass seeds to occupy their time until the dog moves on. Most of the Chipping Sparrows have gone high, but the Palm Warblers are more confiding – indeed, I’ve always found them to be the most trusting of warblers, often allowing full minutes of unobstructed viewing. Their habitat and incessant tail-bobbing makes them easy to pick out even before I spot the rusty cap and yellow under-tail coverts. So, rather than wasting precious time scrabbling through my field guide or wracking my brain to remember which eyestripe belongs to whom, as I might with some other species of fall warbler, I just enjoy them. And if they were unfamiliar, if I was never in a place where I saw them every trip for a month or more at a time, would I be able to do that? Not as easily.

As the sun gently dries the grass and Flickers flick overhead, the Palm Warblers and I sit in the weeds. I don’t need any more glamour than that right now.

Leave a Comment