Tenijah Hamilton (she/her) is a multi-hyphenate creative most known for her time as host and producer of the podcast Bring Birds Back by Birdnote. As a self-proclaimed Bird Girl in Training, Tenijah has spent time interviewing all types of bird nerds, from leaders of the Black Birder’s movement to raptor handlers on movie sets to influential environmentalist Bill McKibben. One of Tenijah’s deepest held convictions is that people don’t have to be experts or go anywhere to bird and that true accessibility, equality, and impact in the bird world comes from validating every person’s unique journey to caring about their feathered friends.

You were involved in the publication of “The Joy of Birdwatching”, a recently published book. Can you tell us a bit more about your involvement?

I was grateful to be asked to contribute both an entry and the foreword to the book by the Lonely Planet team. It was such an honor and I really relished the opportunity, as someone who cut her teeth in the bird world through audio, to be able to flex my muscles as a writer to reflect on both what my birding journey has meant to me and the beauty of birding in Atlanta, Georgia.

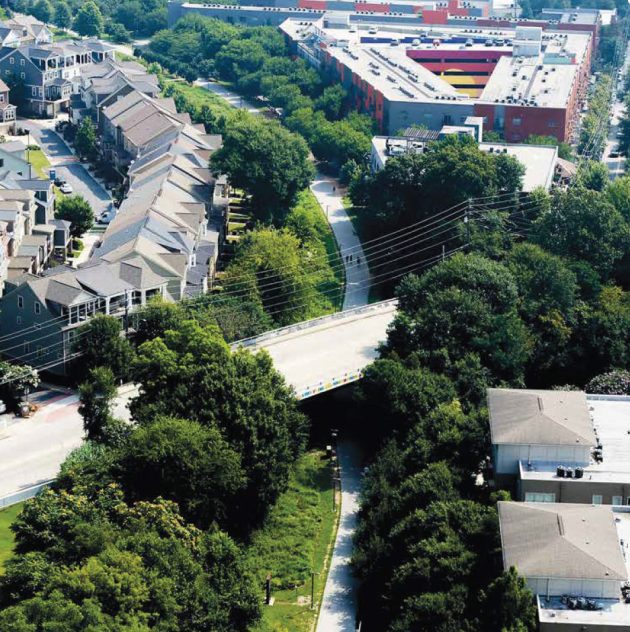

You contributed a section on the Atlanta Beltline. What is your connection to that particular location?

I moved back to Atlanta from Boston in 2020, and one of the things I had been absolutely spoiled by while living in Massachusetts was the integration of greenspace into public life. For example, you have these sprawling campuses in Cambridge with all of this tree canopy and buildings with centuries-old creeping Ivy and it just feels so much a part of the lifeblood of the area. I remember in the early days of COVID, they shut down a busy street corridor near me so people could walk it because it bordered the Charles River and it was the proximity and access to nature—and the fact that it was right outside my front door—that appealed to me the most.

Atlanta is known as the city in a forest because there are so many trees, but what was missing, for me at least, was the connection to everyday life. That’s why when I moved back down South, I became enamored with the Beltline. It’s a roughly 30-mile stretch, accessible from many points throughout the city, and it really fuses nature, urban architecture, retail, and recreation. And luckily for me, there are some truly awesome spots to catch some birds along it.

Atlanta Beltline

Can you tell us a bit about your experience writing this section? Did you learn anything while preparing it?

I learned a ton while writing this section.

What really stood out to me was all the intentionality that went into the creation of the Beltline. It was and is a joint effort that included everyone from council members and urban planners to arborists and community members. In the podcast I used to host and produce, I remember working on an episode live from the Beltline where I volunteered with Trees Atlanta to plant native plants like Bee Balm for pollinators (and in turn, Chimney Swifts, who had been built towers at that location to perch on). I learned so much more while writing this piece about all the people power it took to bring this urban green space to life.

Do you have any other locations described in the book that you felt were particularly interesting? Have you been to some of them? Which is the one you would like to visit most?

I used to live in Wellington, New Zealand and I was chuffed, as the Kiwis say, to see there were a couple of spots that were mentioned in the book! One of those places is Kapiti Island, and excitingly, I have a visit there planned for next Spring. I’m really looking forward to being in one of the most pristine and well-protected natural habitats in the world and seeing what birds I meet there!

Southern Brown Kiwi (Tokoeka) on Ulva Island, New Zealand

In your foreword to the book, you highlight the increased diversity among the birdwatching community. Can you tell us a bit more about that?

For me, it’s been really interesting to see how in the years since 2020, people from historically marginalized communities including BIPOC and LGBTQAI+ folks, as well as those traditionally without access to nature and those with disabilities, have flocked (no pun intended) to the world of birding. Make no mistake, there have always been people who are part of those groups in nature, but it just felt like a movement—and that’s in no small part thanks to the people who built coalitions and did community building like those who started Black Birder’s Week. What I think was most spectacular about that moment in time is that we didn’t wait for an invitation into those spaces by the gatekeepers, we reclaimed those spaces and invited others to enjoy them alongside us. I am so proud of that, and at the same time, I can hold that the work is not finished. There’s more to do and build, and ‘diversity’ isn’t a dirty word.

Yellow-rumped Warbler

Is there anything else you would like to share with the readers of 10,000 Birds?

Birds are really incredible, and I would encourage readers to get to know some of the citizen science projects going on in their communities so that they can be better stewards of nature and advocates for our feathered friends. There are things like the Christmas Bird Count and the Birdsong Project that really help us to capture this specific moment in time and ecological history, so if you can, try to be a part of that.

Leave a Comment