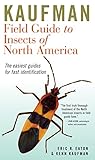

The acquisition of a new field guide is always a joyous occasion, signaling either an impending journey or impending answers to old questions. By the latter, I’m referring to those unclosed cases that accumulate any time a nature lover ventures outdoors armed with a camera but not a clue. As you can imagine, my digital archives are filled with photos of all manner of bloom and beast just begging for identification. When my copy of the Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America arrived, it was clear that some answers were nigh.

The acquisition of a new field guide is always a joyous occasion, signaling either an impending journey or impending answers to old questions. By the latter, I’m referring to those unclosed cases that accumulate any time a nature lover ventures outdoors armed with a camera but not a clue. As you can imagine, my digital archives are filled with photos of all manner of bloom and beast just begging for identification. When my copy of the Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America arrived, it was clear that some answers were nigh.

Invertebrate identification isn’t my strong suit. Perhaps this is why I appreciate the Kaufman guide so much. This resource does not purport to be the definitive primer on all North American insect life. How could it be while maintaining such a portable profile? Bird watchers accept 10,000 as a nice, round estimate of all the world’s avian species, and yet struggle with the subtle differences between a handful of flycatchers or warblers. The lot of an invertebrate enthusiast seems infinitely more daunting when one considers that there are over 16,000 species of flies in North America alone. How can one begin with the basics when every single order is represented by a myriad of minuscule possibilities? That’s why the designers of this guide wisely chose to concentrate on the most common representatives of a broad range of genera.

Of course, this approach sounds sage in theory but may fail if the guide does not provide either a solid identification or at least a solid lead when put to the test. This is where my archives come in. Behold my mystery moth (and those of you who recognize this species shouldn’t give it away to the rest of the class!):

This luminous interloper dropped in at our annual poker match at the 2006 Chicken Inferno. Since my cards were nothing to speak of, I held up the game in order to shoot a few portraits of the mystery moth. My father-in-law and uncle both referred to is as an underwing moth, something I’d never heard of, so at least I had a place to start my inquiry.

The Kaufman Guide has a simple, intuitive layout. Knowing that there are around 11,000 identified species of moth in North America, I was surprised to note that only 43 pages are devoted to moth identification. But a mere 4 pages on underwing moths were enough to establish that my mystery moth was not a member of the Noctuidae family. It is true that many members of the genus Catocala have telltale bright hindwings, but none of these drab brown, black, or gray moths look like our subject. That’s what I get for trusting a marine biologist and geologist on matters of entymology.

The restricted number of pages devoted to moths turned from a potential liability to an actual asset when I quicky found a match, not just in family but in species. My mystery moth appears to be a Virgin Tiger Moth (Grammia virgo), one of the most attractive Arctiidae moths around. Success!

The bottom line is that this guide seems ideal for casual or modestly skilled insect oglers like myself. More than 2,350 digitally enhanced photographs representing every major group of insects found in North America north of Mexico make the book a treat to work with. Informed by a philosophy of “naked-eye entomology”, the Kaufman guide offers information on those lifeforms most apparent to the naked eye. Due to a lack of depth as well as an absence of features as basic as range maps, this guide cannot replace more comprehensive resource books, nor is it likely to please experienced invertebrate watchers. From what I can gather, it isn’t meant to. The vast, teeming hordes of North American insect life cannot be understood all at once, but the Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America offers an ideal place to begin.

I haven’t bought this yet, but have used it a few times at the bird observatory to look things up. Like you, I’ve found it very easy to use and agree it’s probably a good guide to start with. Much better than my audubon guide to insects that just confuses and frustrates me.