Back in July, my fellow 10,000 Birds contributor Dragan wrote a delightful piece about birding Lake Kerkini in spring. I first visited Kerkini and this bird-rich region of northern Greece 15 years ago, and have been returning regularly ever since. While spring is undoubtedly the most rewarding time to visit, I’ve enjoyed several autumn and winter trips, too, made more enjoyable by the fact that the weather is usually much sunnier, and warmer, here than it is at home in the UK. Last year, in November, I notched up a dozen species of butterflies, an impressive total anywhere in Europe so late in the year.

For the autumn or winter visitor, the biggest draw is the flock of Lesser Whitefronted Geese that in recent years have been regular and reliable wintering birds on the lake. I’ve seen them on every autumn visit to Kerkini, but despite many encounters, I’ve yet to get close enough to get a decent picture of them. (My photograph below is of a captive bird). Usually they are several hundred metres away, and it takes a lot of hard work with the telescope to make sure that they are indeed Lessers, and not the Greater Whitefronts that also winter here. They are, of course, a smaller more compact goose, but picking out the various distinguishing features (such as the yellow eye ring) at such range is invariably challenging, to say the least. Often the best clue is counting the flock. If you look on the Portal to the Lesser White-fronted Goose (https://www.piskulka.net/) you can check on the current flock size: if the flock you find is almost exactly the same size as that reported on the Portal, then you can be pretty sure that you have found your quarry. It’s an unusual way to identify a bird, but it’s reliable.

Perhaps curiously, the Greater and Lesser Whitefronts never seem to mix. Perhaps they do occasionally, but not when I’ve seen them. Red-breasted Geese do turn up at Kerkini regularly, and one year I watched a Red-breast mixed in with the Lessers. Red-breasted geese are so distinctive that you would think that they would be easy to pick out in a flock of grey geese, but surprisingly that’s not the case.

Lake Kerkini is an artificial lake, its depth varying considerably throughout the year. It’s always at its lowest in late autumn, and this can be frustrating as the birds – and there’s always lots of them – are usually very distant. Even if you take a boat ride out on the lake (recommended), the shallowness of the water will restrict how close the boatman will be able to take you to the birds. However, you are certain to get great views of Greater Flamingoes, as several thousand winter on the lake. By November nearly all the White Pelicans have gone south (there always a chance of seeing a young bird that has been left behind), but you are certain to see plenty of Dalmatian Pelicans, one of Europe’s rarest birds, but a common resident here.

Kerkini’s Dalmatian Pelicans lure photographers from all over Europe. The most popular month for pelican photography is February, when the Dalmatian’s beak pouch is an intense shade of red-orange. (They soon lose the colour as the spring progresses). The pelicans have developed a special relationship with the Kerkini fishermen, so have become tame, approachable and very photogenic.

Kerkini does, of course, attract tremendous numbers of wintering wildfowl, including huge numbers of Common Pochard, by far the most numerous of the diving ducks. You might, if you are lucky, see a few Ferruginous Ducks, too, and perhaps even a Red-crested Pochard, but I have yet to see a White-headed Duck here, though they have been recorded. There’s always good numbers of all the surface-feeding ducks that you would expect, from Pintail to Eurasian Wigeon. Both Bewick’s and Whooper Swans occur in good numbers.

One bird that has notably increased in numbers in recent years is the Common Crane, with January counts of up to 140 birds. Overwintering Black Storks are normal, while Spoonbills (which nest in the drowned forest on the lake) remain in some numbers until late in the autumn, possibly overwintering. A feature of the autumn is the abundance of Great White Egrets – up to 200 on the lake – but as far as I know they have yet to breed here.

Though the lake may be the main attraction, it’s the rich variety of surrounding habitats that make the area so interesting for the visiting birder. In the UK we have a mere three resident woodpeckers, but in the vicinity of Kerkini it’s not difficult to find all of Europe’s peckers except the Three-toed. Middle-spotted can be found in most of the woods and forests, Syrian are frequent in the villages, while Lesser-spotted (now a rare bird in the UK) are pleasingly common. In the course of a week you will be unlucky not to connect with both Black and Grey-headed, and it’s only the White-backed (here of the race lilfordi) that’s likely to be a real challenge. I’ve only found one once, but it was a delightfully confiding bird.

Of the Balkan specials, Sombre Tit tends to be quiet and unobtrusive, so can be a challenge to find. Some years Rock Nuthatches are easy to locate (try any of the local quarries, or the cliff face below the castle of Sidirokastro), but in others they can be elusive. Wintering Wallcreepers are always a possibility, too, generally in quarries where Eagle Owls are resident.

Mention of Eagle Owl brings me to to rich variety of raptors to be found here in winter. Both Golden and White-tailed Eagles are resident and can be found all year, but Spotted Eagles are a winter special, and there’s usually a dozen to be found wintering on and around the lake. Such an abundance of wildfowl attracts Peregrines. One year we found an impressively big calidus Peregrine, feeding on a Wigeon that it had killed. A wanderer from the arctic, we thought at first it might have been a Saker, a bird I have yet to see here.

Disappointingly, mammal encounters are few, other than the odd Roe Deer. Golden Jackals have been increasing in recent years, but they are shy and you are more likely to hear them at night than see them. Otters are regularly reported, but I’ve yet to see one here, but I have had a number of encounters with Wild Cats, which are quite common and may even be encountered during the day. Kerkini’s most famous mammal is the domesticated Water Buffalo – large herds are kept around the lake. Despite appearances, they are remarkably docile.

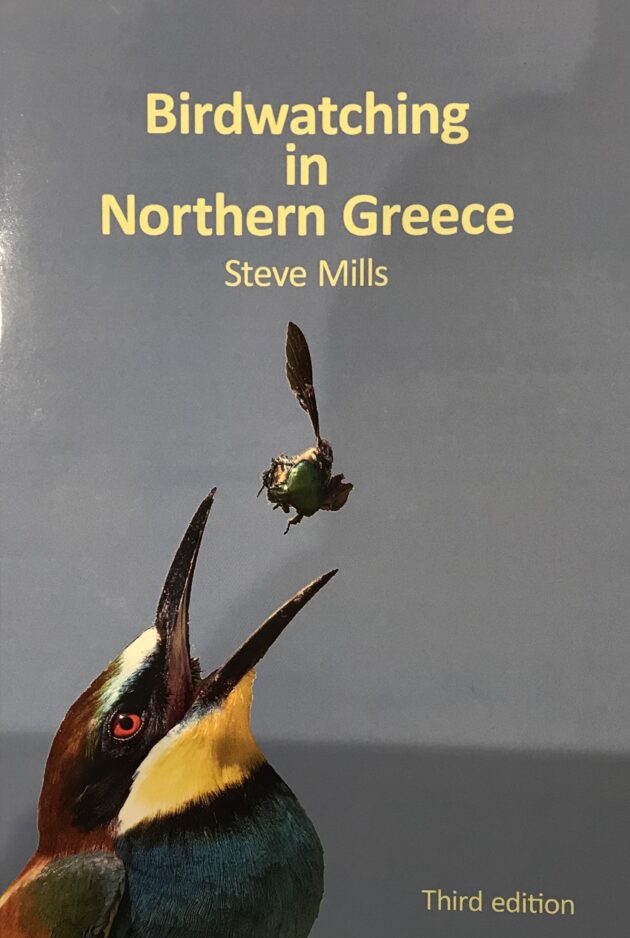

A week’s winter birding should produce a tally of anything from 120 to 130 species, depending on how hard you work, luck and the weather. For more information, I strongly recommend Birdwatching in Northern Greece, the third edition of which was published recently. Its author is Steve Mills, the founder of Birdwing, an organisation that has done much to raise awareness of bird conservation in North-East Greece. Steve is a talented photographer: his excellent pictures add greatly to the appeal of the book. By the way, at the time of writing in mid-November, there was a record flock of 141 Lesser Whitefronts on Kerkini, up from a mere 25 just 14 years ago.

Thank you, David, for this amazing article. What struck me was you mentioning that wallcreepers are usually found in quarries where Eagle Owls breed. Do you think there is an ecologic connection? This would be difficult to investigate here in Germany where nowadays essentially every quarry has a pair of Eagle Owls, so I am really curious.

I don’t think that there’s an ecological connection between Eagle Owls and Wallcreepers. My feeling is that they both favour the same habitat. We don’t officially have Eagle Owls in the UK (other than the odd pair of escaped or released birds, which have bred in northern England) so Eagle Owls are much sort after by British birders. We are pretty keen on Wallcreepers, too, as they are very rare visitors to England. I’ve yet to see a Kerkini Wallcreeper, but I’m still trying.

Thanks for this article, David! As I read this, I am briefly in western Turkey, so all this information is helpful. I did see a small flock of overwintering flamingos yesterday, on an outing cut short by a rain squall. This month’s abundant rains bode very well for the eastern Mediterranean, but they haven’t favored outdoor activities.

I hope to put up a report of my own soon, if only I can finish understanding my new lightweight mirrorless camera, bought to make travel easier, and its accompanying software. I feel my age every time I confront a new set of technologies.