And so it’s July, which for this North American birder means a couple of things: 1. southern Australia’s cool winter weather and wonderful birds sound mighty appealing right now and 2. I, like many of you, eagerly await the release of the AOU 52nd checklist supplement, even though these days, the contents are already pretty well known in advance.

My column this month will be shorter than usual due to my recent relocation to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, but I was excited to discover that a synthesis paper on higher-level avian relationships that had caught my eye several months ago is now available online in its entirety: Metaves, Mirandornithes, Strisores and other novelties – a critical review of the

higher-level phylogeny of neornithine birds (PDF) by Gerald Mayr, a paleornithologist at Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum in Frankfurt, Germany.

A Speckled Mousebird (Colius striatus) poses in Nairobi. Mousebirds remain one of the mysteries in avian systematics. Photo © David J. Ringer.

In many of his papers, Mayr seeks to reconcile comparative molecular (DNA) and morphological (physical characteristics including bones and muscles) data sets to arrive at a unifying theories of avian relationships, bridging the divides that can occur when molecular systematists and morphologists each insist that their data and interpretations provide the only possible explanation of avian relationships.

Mayr quite reasonably argues that both approaches can produce false results by failing to eliminate uninformative similarities (e.g., convergent aquatic adaptations of loons and grebes on the morphological side and certain molecular sequences on the DNA side) and that by synthesizing all available information, we can both achieve greater confidence in hypothesized relationships and expose areas needing further research.

Through the course of the paper, Mayr puts a slew of recent studies (including Hackett et al.’s landmark 2008 paper) in the context of each other. The following points stood out to me:

- “Metaves,” a collection of disparate and puzzling birds recently grouped by the position of a few molecules in one nuclear gene, is probably not an actual clade. Some birds placed in this group (like tropicbirds) have morphological features that argue for their placement elsewhere, but many others are just oddballs, and their relationships are not resolved.

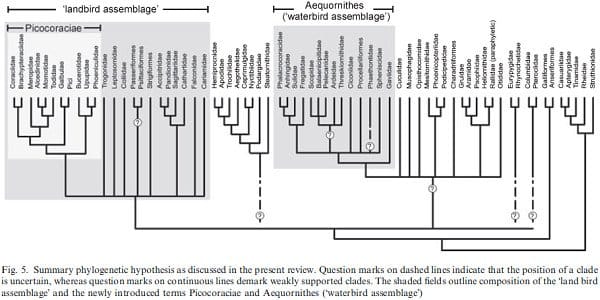

- Mayr names an assemblage of waterbirds Aequornithes. This group includes the Suliformes, Pelecaniformes (as newly redefined), storks, tubenoses, penguins, loons, and perhaps tropicbirds.

- The unlikely flamingo-grebe group, Mirandornithes, is very strongly supported by multiple data sets (nuclear and mitochondrial DNA, certain anatomical features, eggshell composition, and shared parasites) despite criticisms from more conservative morphologists. This clade, Mayr says, is “most likely the sister taxon” of Madagascar’s terrestrial mesites (!).

- Mayr takes the position that doves and sandgrouse are sister taxa because morphological evidence is good even though genetic evidence is murky.

- Mayr uses the name Strisores for a clade containing swifts and hummingbirds and the former Caprimulgiformes, within which swifts and hummingbirds are embedded. No clear genetic or morphological signals have yet been identified to indicate how this group of remarkable birds is connected to other major clades.

- A clade Mayr calls Picocoraciae is well-supported and includes rollers, kingfishers, bee-eaters, motmots, woodpeckers, hornbills, and hoopoes. The relationships among these families have been pretty well sorted out, and the entire clade belongs in a clade of landbirds (passerines, parrots, diurnal raptors, mousebirds, owls, etc.) whose full make-up and internal relationships are not resolved.

Here’s Mayr’s hypothesized phylogeny, which he concedes is “still quite comb-like,” but he expresses optimism that fuller resolution is within reach. What do you think?

So add one more species to the Chisos trip: Mexican Jay, yay.

Interesting that the Sungrebe/Kagu clade is still unrooted.

@Lisa – The Mexican Jay split (if carried out in the final publication the way it’s presented in the proposal) will split off Mexican Jays in the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt as Transvolcanic Jay but will leave the Sierra Madre Occidental and Sierra Madre Oriental races as one species, Mexican Jay. So the forms seen in Texas and Arizona will still be considered the same species.

@Duncan – Yes, while Kagu and Sunbittern are well supported as sister taxa, their position relative to other clades is anyone’s guess. Mayr lists molecular studies that place them as sister Cuculiformes, Falconidae, and Ciconiidae, and points out a myological feature shared with grebes (and rheas). Take your pick!