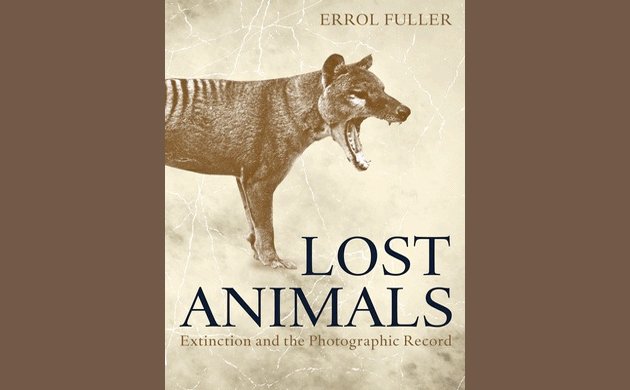

One of the reasons I enjoy about reviewing books is the opportunity to read titles I wouldn’t ordinarily encounter, not because they aren’t good but because they don’t fall easily into a category. Lost Animals: Extinction and the Photographic Record by Errol Fuller is one of these books. Yes, it is about extinction, a popular topic in the Year of the Passenger Pigeon. But it examines extinction in a very different way. Most of the books about extinction, including Fuller’s Extinct Birds (now, ironically, out of print), describe what was lost and look for explanations, scientifically and historically. Lost Animals is a book about what was lost and witnesses to the loss—how the bird or mammal was viewed, often for the last time, through the lens of a camera. And, in a strange way, it’s a book about hope.

Female Imperial Woodpecker in flight, Mexico, a still from recently found film made by William Rhein, p. 115.

The idea of Lost Animals was conceived after the publication of Extinct Birds (2001), a 400-page, four-pound book on 75 extinct species. The book was illustrated by many beautiful paintings and a few photographs that were, as Fuller himself says in the Introduction to Lost Birds, of poor quality. Yet, the photographs exerted an unexpected pull over readers. “They would pause over them and just gaze, sometimes even raising the book towards their eyes in the vain hope that this action would allow them to see more.—more than there really was to see!” (p. 8). And so, Fuller embarked on a new initiative—locating and researching photographs of lost birds and, expanding his scope, of mammals.

Passenger Pigeon chick in aviary, 1896, photographer’s identification uncertain, photo now property of the Historical Society of Wisconsin, p. 67.

Lost Birds looks at photographic representations of 28 species, 21 of which are birds. (Two creatures, Heath Hen and Quagga, are actually considered subspecies, but are so well known and are represented so well photographically, that Fuller felt justified in including them.) The photographs span the years 1870 to 2004. Some were taken of birds and mammals in zoos or aviaries, others were taken in the wild, often in remote places. Some document one of the last views of the species, others are of the last representative of the species.

The earlier photographs were taken with the equipment of their time, meaning large machines that utilized wet plates and required good light. Thus, the earlier the species has died out, the fuzzier and grainier the photo. Even some of the more recent photographs are of less than stellar quality, reflecting the geographic isolation of many of these species and the plain difficulty of photographing birds that skulk, live on volcanoes, or disappear for years at a time. (Still, it does seem incredible that better photos could not be taken of Bachman’s Warbler.) Fuller honors the photographic record by reprinting the images untouched. What you see is what the photographer saw, filtered through the light and the photographic technology.

10,000 Birds readers will recognize about half of the bird species. Eskimo Curlew, Passenger Pigeon, Ivory-billed Woodpecker, Bachman’s Warbler, Carolina Parakeet—these are names that echo mightily through birding histories and even some recent field guides. (The 6th edition of the National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America, for example, includes “extinct” and “probably extinct” species in a chapter, mixed in with accidentals.) Other species are less known. Their stories are related by Morris in a narrative style that combines facts with anecdotes, dates with speculation. The chapters are just as much about the photographs—who took them and why—as about the creatures themselves. And, they are fascinating.

Laughing Owl, 1909, New Zealand, photo taken by Cuthbert and Oliver Parr, pp. 90-91.

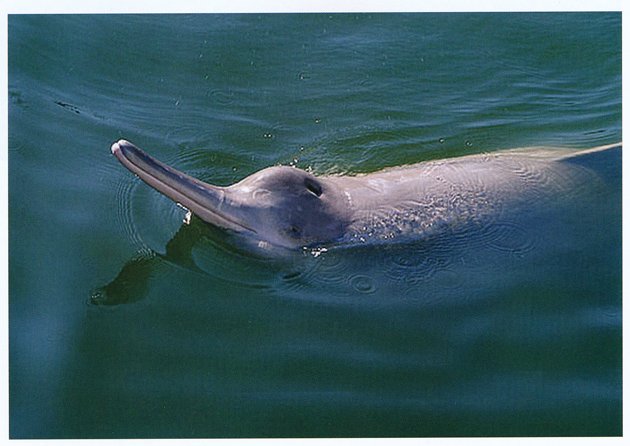

There is the flightless Atitlán Giant Grebe of Lake Atitlán, Guatemala, whose habitat was destroyed by a combination of human incursion and earthquake, but whose DNA lives on in hybrids that fly. The grebes were well photographed by a photographer sent by National Geographic. The photographs were never published. The Laughing Owl of New Zealand exhibited an apparent lack of fear of strangers and a propensity to spend time on the ground, making it easy pickings for introduced predators. Two brothers climbed up to a nest site in 1908, lifted a nestling out, and gave it a dead mouse (extreme baiting?). Their photos are the only known ones taken of the owl in the wild. The Yangtze River Dolphin (the mammals described here are no less fascinating than the birds), iconic in Chinese culture, had its habitat was destroyed by a combination of human-introduced factors, including the blocking of the dolphins’ echolocation systems by large ships negotiating the river.

Yangtze River Dolphin in captivity, 1988, Wuhan, China, p. 192.

And, then there are the extinct birds of Hawaii, four of which are represented here— Kaua‘i ‘O‘o, `O`u, Po?ouli, and Mamo (also known as Hawaii Mamo). Their names echo musically in my brain (and challenge my typing skills) as I look at photos fuzzy and sharp, and read tales of habitat encroachment, avian disease, and hunting. The story of the Mamo is particularly poignant. Hunted in the thousands for their yellow feathers, which were used to create the royal cloak and other garments for Hawaiian royalty, the bird was considered extinct by the end of the 19th century.

Mamo, held by Ted Wolstenholme, 1892. Hawaii, photographer may be Ahulan, his assistant, p. 155.

A photograph taken in 1892 represents one of the last of the species. It’s a shadowy photo of a man holding a tiny bird, recently captured. We can barely make out the shape of the bird, much less the prized yellow feathers. A hand-colored lithograph reproduced at the back of the book illustrates the bird better–black with yellow feathers on the wing, the tail, and thighs, the long bill curved, ready for honey eating. Ironically, the bird in the photograph served as the model for the bird in the lithograph; it was killed, skinned, preserved and stuffed a few days after the photograph was taken.

Still, I look at the lithograph, colorful and detailed, and then I flip back to the fuzzy photograph and hold it up to the light. I think I can see a tiny bit of yellow on the wings. Or, is that from a lack of image resolution? The head doesn’t look black, and I wonder if that’s an effect of late-19th century photographic techniques or if the bird looked different when it was alive. I understand why Fuller created this book. I look at the lithograph and appreciate the bird’s lost grace. I look at the photograph and I am engaged in thought and wonder and sadness. I ache that I will never see what the photographer has seen, but hope that maybe if I try hard enough I will see some kind of echo of this experience in the image.

A lot has been written about photography, about how taking a photograph makes us feel we have power over our subject, how images are the equivalent of our histories, how photographs define communities. Fuller, who has spent a lifetime writing about extinct species, doesn’t venture into philosophy. But, he does understand how the telling of the photographic record aids in communicating the uniqueness of each creature.

Albabra Brush Warbler, 1975, taken by Robert Prys-Jones, p. 131.

Sometimes, the photographs themselves take on the persona of the extinct object. In 1999, Fuller travelled to Tring to interview Robert Prys-Jones, the ornithologist, one of the few people to see the Aldabra Brush Warbler, a bird that existed on a remote coral island in the Indian Ocean. Almost as an afterthought, Prys-Jones mentions that he has a photograph and finds it after rummaging through his desk. Fuller’s astonishment at locating this “grail of extinct-bird photograph hunters” is contagious. It’s almost as good as finding the bird itself! Well, not quite, but the story of how the warbler was found and photographed, the difficulties of just finding the bird, and then seeing it in the foliage, of using film in a place hundreds of miles from a darkroom, help us appreciate our culture’s instinct to capture and save the moment. Even if we can’t save the bird.

Lost Animals is beautifully produced, on thick paper that enables us to look, really look, at the photographs that are the core of the book. Even the fuzzy images have life. As a bonus, Fuller has included a 30-page Appendix offering color paintings of selected birds and mammals; those that he thinks are not adequately represented in sharp detail or in color by the photographic record. The book has an excellent index, noting pages of images and pages of chapters.

I was happy to see a list of books Fuller recommends for “Further Reading”. As I noted above, his species accounts are very readable but they are not comprehensive. Additional sources are highly recommended if you are searching for a complete account of one of these extinct creatures. Nor is Fuller neutral. In a world of uncertainty as to the why of extinction, he doesn’t hesitate to say when he disagrees with certain lines of reasoning or to take sides in a controversy. Writing about Don Bleitz, who has been accused of using a stuffed bird for his photographs of Eskimo Curlew, Fuller states that there is “no entirely convincing reason to doubt Mr. Bleitz’s honesty” (p. 58.). And, in reaction to writers who say that the de-feathering of the Mamo did not kill the bird, he writes that it is “barely credible that a small creature like the Mamo…would survive such a violent, shocking and debilitating act” (p. 157). These are not the words of a scientist. They are the words of a writer who cares passionately.

Lost Animals: Extinction and the Photographic Record is a unique book; it connects us to lost birds and mammals through the medium of their images. It is a book for birders who want to enhance their readings of BirdLife International records and Passenger Pigeon and Ivory-billed Woodpecker histories with an approach that is visual and personal. Reading the stories of these extinct creatures evokes sadness and anger, yes, but, as I said earlier, it also brings out hope. I’m not just talking about the few instances where Fuller says there is the slimmest of slim chances that the bird is not extinct. There is hope because extinction is being witnessed. And remembered. It’s a lot harder to ignore conservation campaigns to save habitat when you’ve seen the ‘photographic record’ of what happens when you do. This is probably a naive statement to write in the face of articles and books placing us on the edge of a “sixth extinction”. I am taking my cue from Fuller, who finds vitality in old, fuzzy photographs and who, I suspect, really does hope that by unearthing more archival images of the dead he can somehow keep all species alive.

——————————-

Thank you Princeton University Press for providing a review copy of Lost Animals.

Lost Animals: Extinction and the Photographic Record

by Errol Fuller.

Princeton University Press, 2014 (also published by Bloomsbury Publishing, London, 2013).

240 pp. | 8 x 10 | 53 color illus. 95 halftones.

ISBN: 9780691161372.

Hardcover, $29.95.

Leave a Comment