By Martin Garwood

Martin has been interested in birds from an early age and has traveled extensively in pursuit of different species. He has a particular passion for Swifts. He recently set up a charity, High Weald Swifts, to promote conservation in the UK of this now “red-listed” species. Martin spent his working life in primary education, was formerly a trustee of Kent Wildlife Trust, and as a keen wildlife photographer, completed a Masters’s degree in photography in 2015. He lives in Southeast England, writes articles about wildlife for local journals, exhibits his photos, and gives talks. He is rarely seen without a camera and binoculars around his neck.

A few years ago, I found a book in a local bookshop that was being sold at a hugely discounted price. It has since proved to be a valuable source of information, adding an extra layer of interest to my birding. “Biographies for Birdwatchers” by Barbara and Richard Mearns was published in 1988 in both London and San Diego. The book’s focus is on the lives of those people commemorated in Western Palearctic bird names.

Set out alphabetically, short chapters tell the stories of key bird finders from Edward Adams (White-billed Diver, Gavia adamsii) to Alexander Wilson (Wilson’s Storm Petrel, Oceanites oceanicus, and others). It is a great read, full of the trials and tribulations of the largely eighteenth and nineteenth-century naturalists and adventurers, at a time when much of the world map and its avifauna was only faintly penciled in. Recently returned from a birding trip to Georgia, where the Güldenstädt’s Redstart was one of the star birds, it was this book that was one of the first that I reached for when home to find out more about the bird’s finder and his story.

A trio of males on Sea Buckthorn bushes near Stepantsminda

The Güldenstädt’s Redstart (Phoenicurus erythrogastrus) is a beautiful and charismatic bird, and on this winter trip, I was fortunate to see many. It is essentially a high-altitude species usually found above the tree line and up to the highest peaks of the Caucasus and into the Himalayas. It breeds on alpine meadows and rocky areas at up to 17000 feet. Two sub-species are known. It is a large member of the Redstart clan, built stockily, the male being rusty red and black in colour with a white crown and nape, and huge broad wing patches.

On its high Spring and Summer grounds it is a challenging bird to find; on a group trip in May 2019 to the area, we found just one individual. In winter, however, it leaves the high peaks, descending to the valleys and foothills to find the food it needs and here, changing its diet from eating insects to feasting on Sea Buckthorn berries, it can be numerous and easy to enjoy. It is a fine bird, stunning in flight, and like most redstarts happy to show itself off perching on the tops of bushes or chasing off rivals. Over several days in suitable habitat near Stepantsminda, in the north of Georgia, my birding group recorded seeing over 70 individuals of both sexes

The white wing bars are very showy in flight

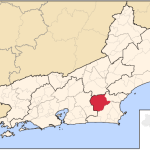

A certain Johann Anton Güildenstädt was the first person ever to record and describe this dashing and then new-to-science species. Johann was born in Riga on the 26th of April 1745. During his short life, he was to become well-known as a zoologist, geologist, and botanist. In 1768 he joined an expedition led by Peter Simon Pallas (Pallas’s Warbler, Phylloscopus proregulus, and others), setting out from St.Petersburg to explore eastwards into the hinterlands of Russia. Heading south over the next few years, Güildenstädt, crossed the Caucasus mountains where he found the redstart now named in his honor.

His travels were to take him through landscapes dominated by hostile tribes to the edge of the Caspian Sea where he became the first person to describe the Terek Sandpiper (Zenus cinereus) He returned to St Petersburg in 1775 and just a few years later in 1781 he was struck down by a local epidemic and died, aged 36, before he was able to publish all his findings, a task taken on later by his colleague and fellow ornithologist, Pallas.

We live in a world where travel is easy, new species of bird are very rarely found and more and more are going missing through habitat loss and climate change so it is hard to imagine both the challenges and excitements of these early naturalists. Seeing those wonderful redstarts in good numbers in their Winter habitat was a great thrill and privilege. I understand moves by the American Ornithological Society to remove the names of the birds’ finders and change them to something less risky but to me, the links to the individual are important reminders of a world and its birds waiting then to be discovered by dedicated and adventurous men and women.

These early ornithologists often faced considerable dangers and risks to life in their quests to explore new regions and record new species. Many would perhaps not agree but in my mind, Guildenstadt’s endeavours should be remembered and celebrated. The proposed new name, White-winged Redstart, is descriptive but really rather dull. I am pleased to have found out a little more about the bird’s discovery; it adds to my enjoyment. If Johann was around today I would shake his hand warmly for introducing this glorious bird to the world.

(Martin traveled to Georgia in March with Birding Caucasus)

Thank you, Martin — I loved your fabulous photos and the background on the explorer who initially catalogued these birds. I’ve been familiar with the work to rename species, because my children’s book about bird conservation will feature the Kirtland Warbler. However, I agree with the efforts to rename species. Currently, so many names are not those given by the people of an area that have known the flora and fauna for millennia, but instead are named for the person who “discovered” them — when “discover” is narrowly defined as writing down for scientific purposes. And in reading this, I realized that I, too, might have felt hostile if a person was investigating my homeland—all too often, there have been ulterior motives such as resource exploitation for those journeys.