When I was a preschooler, I wasn’t allowed to watch much television, but I did get a double-dose of public programming — the PBS station out of Buffalo and the CBC beaming across the border from Ontario both showed a lot of material that met with my mother’s approval and my own. Children’s programming concocted by educators instead of marketers was ok, and so were nature programs.

One of the shows I loved was Fables of the Green Forest, which was some of both. My only hint that this program — actually a Fuji TV production rebroadcast by the Canadians — was based on literature was the theme song, which promised “the stories you’ve read about all come to life.” I never did read about them, and eventually the memory of Sammy Blue Jay, Polly Woodchuck, Reddy Fox, and the rest faded to the back of my mind along with the details of Struggle Beneath the Sea and Sharon, Lois, and Bram.

It’s not surprising that I never ran across the book versions of the Green Forest stories, written by Thornton W. Burgess. Not only did he start publishing his Old Mother West Wind nature stories in 1910, which was just a smidgen before my time — he was also one of the gleeful anthropomorphizers which were superstars in the early years of the 20th century but generally discredited by the time we approached the 21st. He was not overtly accused of being a ‘nature faker’ as Ernest Thompson Seton and William J Long were, perhaps because he wrote for small children, perhaps because unlike Seton and Long he never put his stories forth as anything but fiction — even Theodore Roosevelt, in his attack on misleading natural history, carved out an exception for the writer of “animal fables, avowed to be such.” Nevertheless, Burgess’s overt determination to combine, in his own words, the “teaching of the facts of natural history and the teaching of moral lessons” had long fallen out of fashion by the time I came on the scene.

That Burgess should be so forgotten in the land of his birth that an American child would need to discover him through a Canadian rebroadcast of a Japanese television program would have seemed stunning to an observer in, say, 1917, a year when he published a dozen of his acclaimed short children’s books. So it is pleasing to report that a new biography, Nature’s Ambassador: The Legacy of Thornton W. Burgess, is now out from Schiffer Publishing.

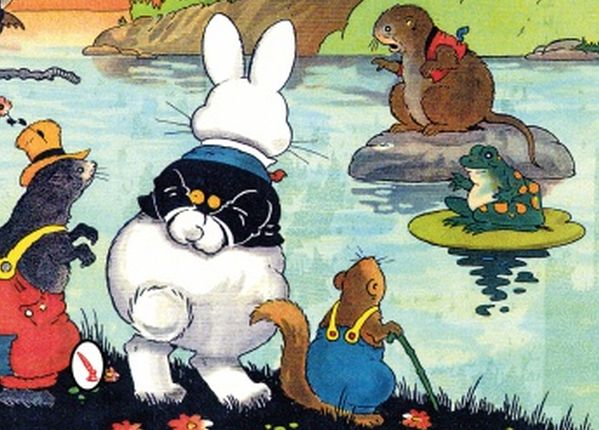

This is a beautiful volume, and one of its primary strength is the lavish selection of illustrations, including both family photos and drawings that adorned Burgess’s stories in various venues. The text, by Christie Palmer Lowrance, offers plenty of primary sources, with extensive quotations from Burgess’s own correspondence and that of his friends and colleagues, along with contemporary interviews with his surviving relatives and with people influenced by his work that range from the poet Nikki Giovanni to Dr. Tom French of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife (not, however, any Japanese animators — the “Legacy”, in the world of this book, does not extend to television, which seems a curious omission.)

Unfortunately, Lowrance doesn’t succeed in synthesizing her material in a way that would raise this biography to the level of ‘definitive.’ Although an alert reader can trace the threads between Burgess’s personal tragedies (including the early loss of his father, the death of his much-adored first wife only months after their marriage, and the estrangement of his namesake son) and impoverished upbringing, on one hand, and his retreat to nature as consoler, his near-ludicrous work ethic, and his attachment to the places and outlooks of childhood, on the other, there is little overt analysis of either the man or the work. Nor, on the other hand, does Lowrance impose the kind of pacing and structure that turns a life into an absorbing narrative. As a result, this book will probably be of most interest to those, like me, who have a preexisting interest in Burgess or in the history of nature writing, along with scholars of children’s literature.

I discovered a couple of his books when a child in the 60’s, and devoured them. One found its way to my own home just last month, when my mother died. It must have worked… Here I am Reading 10,000 birds!