Whiskey Month at Birds and Booze:

This January, Birds and Booze at 10,000 Birds is setting its sights on whiskeys all month long. The cold and dreary dead of winter is as good a reason as any to warm up with a restorative dram of uisce, especially after a blustery morning spent scanning flocks of gulls on an icy shore, trudging through woodland snowdrifts in search of new year-birds, or any other half-crazed birding one does in January. But seeing as the month is also bookended by Hogmanay and Burns Night, we’ll gladly take the opportunity to visit– in spirits, at least – the rugged Celtic landscapes of Scotland and Ireland where whiskey was born and – with luck – have a look at the birds that inhabit them.

In the above preface to Whiskey Month at Birds and Booze, we’re promised “rugged Celtic landscapes of Scotland and Ireland and the birds that inhabit them”. Instead, the first installment of the series last week featured treacly Christmas cards decorated with the cutesy European Robin. Adorable, yes, and befitting of the holiday season, but by now you’re probably expecting more awe-inspiring terrain and hardier, more imposing birds. So, we’ll head across the Irish Sea to Scotland and up the coast to the damp and chilly western Highlands. After all, it’s January, and after getting all the easy feeder birds on New Year’s Day – like it or not – it’s time to go look for gulls.

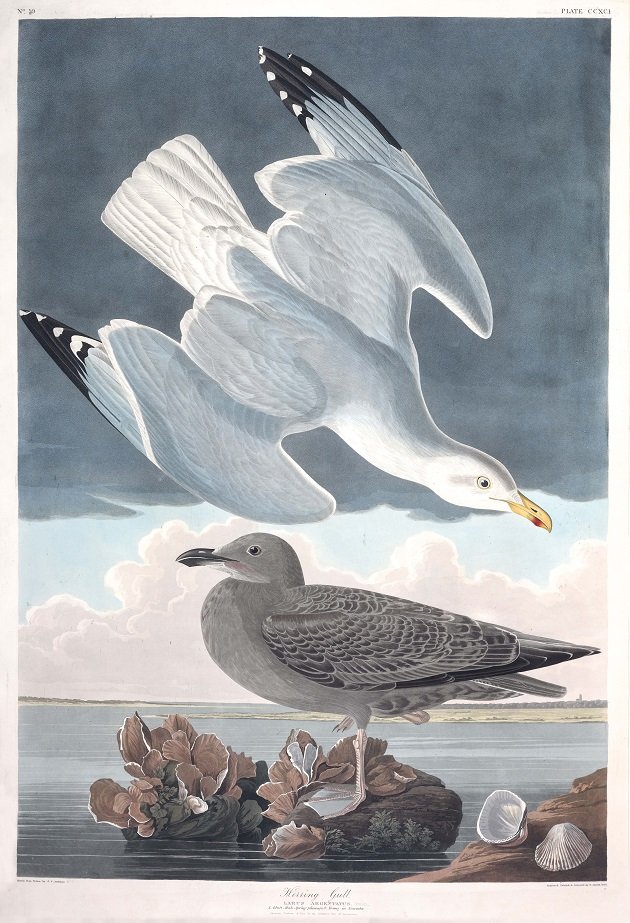

A pair of Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus) from The Birds of America by John James Audubon (1785-1851).

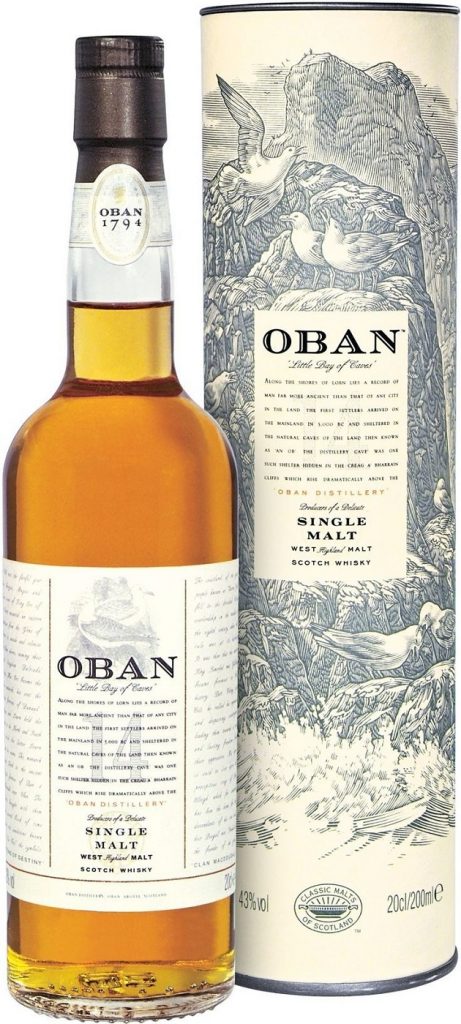

To the general public, members of the family Laridae are mere “seagulls”, crafty and determined summertime bullies dead set on snatching French fries and ice cream out of the hands of unsuspecting beachgoers – and, perhaps thanking them messily afterwards by bombing them from above. But the label of this week’s whisky – Oban 14-Year-Old Single Malt – presents a picture of these birds more familiar to birders: a throng of gulls perched high atop a jagged, craggy sea stack, with icy waves crashing all around below. It’s also a scene more in keeping with our romantic notions about whisky and the sublime and desolate landscapes it evokes – cold, misty places where the land meets the sea and seabirds find refuge in huge, clamorous colonies. But no matter where you find them, the search for gulls is often accompanied by its own brand of self-inflicted suffering, for which whisky is the perfect remedy.

Most birders would readily admit that gull-watching – or gulling, as it’s often called by adherents – is one of the more peculiar and daunting sides of the hobby. Unlike a casual, springtime walk in the park, gull-watching requires perseverance in the face of real hardships: it’s best to come armed with several field guides, several layers of clothing, a tolerance for extreme cold, and a bit of a masochistic streak. First and foremost, gulls are notoriously difficult to identify, presenting subtle variations between species, age, and sex that many otherwise skilled birders never truly master.

It’d be one thing if this head-scratching family of seabirds appeared in their greatest yearly abundance amidst the soothing comfort of reasonable spring weather – like warblers, vireos, and other neotropical migrants are decent enough to do. But many gull species breed – and interbreed – in the Far North, heading south only during the coldest months of the year. For birders in more temperate climes, the dead of the boreal winter is the only chance to catch a glimpse of several species. Be sure to bundle up.

It’s not just the miserable weather gull-watchers have to contend with. In winter, gulls of many feathers tend to flock together en masse, so finding the most sought-after species means picking through densely packed congregations of exasperatingly similar birds huddled tightly by the thousands on windswept, iced-over rivers, or along bleak, rocky coastlines – a drab, Whistleresque symphony of whites and grays. It’s like “Where’s Waldo” with grayscale birds.

More horrifyingly still, scavenging gulls also like to assemble at landfills, where you’re guaranteed all the gull-watching fun advertised above, but combined with the noxious aromas of moldering garbage. It’s worth noting that while many birders will endure the privations of gull-watching only as long as they have to before the first signs of spring appear, hardcore larophiles – widely regarded as the most eccentric of all birders – willingly engage in these deviant activities year-round.

For all these reasons, I suspect some birders turn to a stiff drink after returning home from wintertime gull-watching – undoubtedly with numb fingers, frozen feet, and – quite possibly – crushed spirits. Whether it’s to thaw oneself after hours spent adjusting spotting scope dials in the face of bone-chilling Arctic squalls, or to erase the maddening image of thousands of lookalike gulls from one’s addled mind, or just to expunge the pungent scent of the dump from the nostrils with a jarring shot of liquor, this week’s dram is for you.

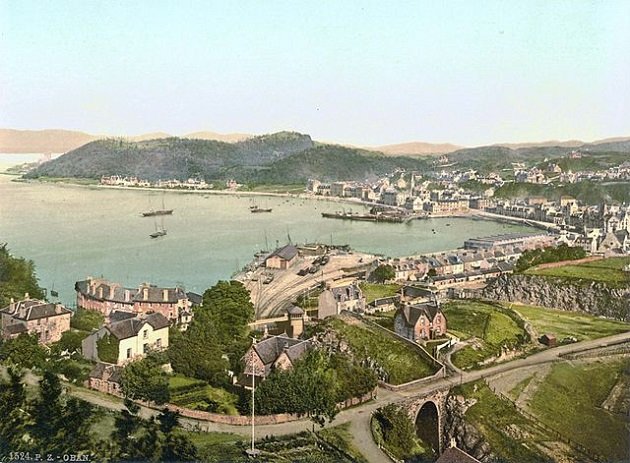

The Oban Distillery was established in 1794 in the western Scottish port of the same name. The name in Scots Gaelic is An t-Òban, meaning “The Little Bay” and before the town grew up around the distillery in the nineteenth century, Oban was the site of a small fishing industry which benefited from a well-protected, horseshoe-shaped harbor opposite the Isle of Mull.

A photographic view of the harbor of Oban around the turn of the last century.

Several gull species are found year-round around Oban, notably Black-legged Kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla), Black-headed Gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus), Mew Gull (Larus canus), Herring Gull (Larus argentatus), Lesser Black-backed Gull (Larus fuscus), and Great Black-backed Gull (Larus marinus). Granted, the monochrome engraving of gulls on the label of Oban 14 doesn’t provide definitive identification clues but the birds depicted seem to be large, white-headed gulls with paler mantles than one would expect for either of the “black-backed” species. Let’s go with European Herring Gull.

A presumed European Herring Gull (Larus argentatus) depicted by Finnish-Swedish artist Ferdinand von Wright (1822-1906).

The Oban Distillery is one of Scotland’s smallest, with only two pot stills, and its range is noted for bestriding the famously smoky whiskies of the Hebrides and the sweeter, lighter style of the mainland Highlands. The 14-year-old expression from Oban displays sweet notes of nutmeg, vanilla, and orange beneath distinctly salty wisps of sea spray and medicinal smoke. There’s a soft, sweet, and oily texture with traces of peat and brine, giving way to rich figs and sweet malt in the middle, with a heady measure of oak and smoke in the spicy, slightly tarry finish.

Like many single malts, the whiskies of Oban are a bit of an indulgence. But if you’re a whisky fan, treat yourself – you just may need it before the season is over. Someday this winter, you’re bound to be out gulling and will probably find a single promising bird out of nearly identical thousands – a potential rarity, perhaps. Except that it’s facing the wrong way with its head tucked in, stock-still and sleeping on the ice. Undeterred, you’ll train your scope on the uncooperative gull, hunching over the eyepiece in the enveloping deep freeze, waiting for the slightest movement from the bird: preening, standing, feeding, nudging the gull next to it, anything. Nothing. After several minutes of aggravating stillness, your patience at its end, you may even be moved to yell at the bird, raining desperate curses on it and all its unhatched descendants. Finally, after an eternity, the gull will budge slightly, showing some previously concealed field mark – only to reveal itself as the everyday species it’s been all along. And when you get home later that day, you’ll be glad to have this restorative bottle of whisky waiting for you in the cabinet.

Good birding and happy drinking!

Oban Distillery: 14-Year-Old Single Malt Scotch Whisky

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Five out of five feathers (Outstanding)

Are any, all of the January whiskeys readily available in the US? As for pricing, what does a bit of an indulgence translate to–as in five feathers?

Hi Lisa. All of the January Whisky/Whiskey Month are available in the United States, at least where I am in the northeast and I expect most, if not all, of them are distributed nationwide. I see Redbreast, Oban, and The Famous Grouse just about everywhere, and better liquor stores should carry Glengoyne (the newest and last post for January) as well. You might have trouble finding the Linkwood since it’s rumored to be discontinued but I’ve seen it in two local shops recently, so it’s worth looking for.

As far as pricing, they’re all under $100, and usually much less. You can certainly pay three- of four-figure prices for more sought-after whiskies, so I picked ones I knew others could probably find (and ones I could afford myself!). Off the top of my head, the Oban, Linkwood, and Glengoyne were around $70 each and The Famous Grouse was around $30. Redbreast was a gift but I think it usually comes in around $50 or $60.

Thanks for reading!