We are on the threshold, just stepping across it really, of understanding one of the most important evolutionary events that ever happened. I speak of flight, of course. This is a key feature of birds. Not all birds fly, but all birds have flight related anatomy and at least descend from those that did. Indeed, we call the very rare non-fliers “flightless.” We don’t call any rodents “flightless rodents” though almost all of them are.

Of all the flying things, only birds were large enough, bony enough, diverse enough in their modern form, and recent enough to have left enough evidence to really see the evolution of their flight.

Flight has evolved multiple times; it has emerged in lizards, snakes, fish, bats, maybe bats again, distant relatives of primates, regular primates, rodents, and a few other unlikely taxa, in a rather half baked fashion, not “true” flight. It has evolved in non-vertebrate animals like insects more than once.

Originally the land was occupied by plantish things, but they formed detritus, so some animals crawled from the aquatic habitat in which they had diversified to eat the detritus. For a long time the plants were mostly left untouched but their dead leaves and protoleaves were consumed by things like ancestral millipedes. Soon after carnivores that could hunt on land evolved, things like ancestral centipedes. So for the longest time, the animal life of the earth ate dirt or each other and consisted entirely of creepy crawly things and nothing else.

Insects evolved around 400 million years ago, plus or minus. It may have been nearly 100 million years before they evolved flight. And, given the way things went back then, it is possible flight evolved a couple or few times before it stuck. So, insects, the ultimate fliers of today’s world, probably took more time to go from terrestrial to flying than the period of time since the last non-avian dinosaurs to the present.

Birds evolved from bipedal terrestrial animals to flying creatures over a roughly similar time range (roughly… meaning, tens of millions of years). We’ve recently seen that ensmallening of the bird lineage was an important part of this.

And, once again, a major evolutionary scenario surrounds mainly predation. Just as early land life (which by the way all went extinct tens of millions of years after it started) involved carnivores quickly evolving (to consume detritus eaters who had been the first on land, early birds probably ate a lot of insects, the initial denizens of the sky. And there would be a lot to eat.

I bring all this up merely as introduction to a very interesting paper, not long out, that I want to point to. Here is the citation:

Xing Xu, Zhonghe Zhou, Robert Dudley, Susan Mackem, Cheng-Ming Chuong, Gregory M. Erickson, and David J. Varricchio. An integrative approach to understanding bird origins. Science 12 December 2014: 346 (6215), 1253293 [DOI:10.1126/science.1253293]

The abstract:

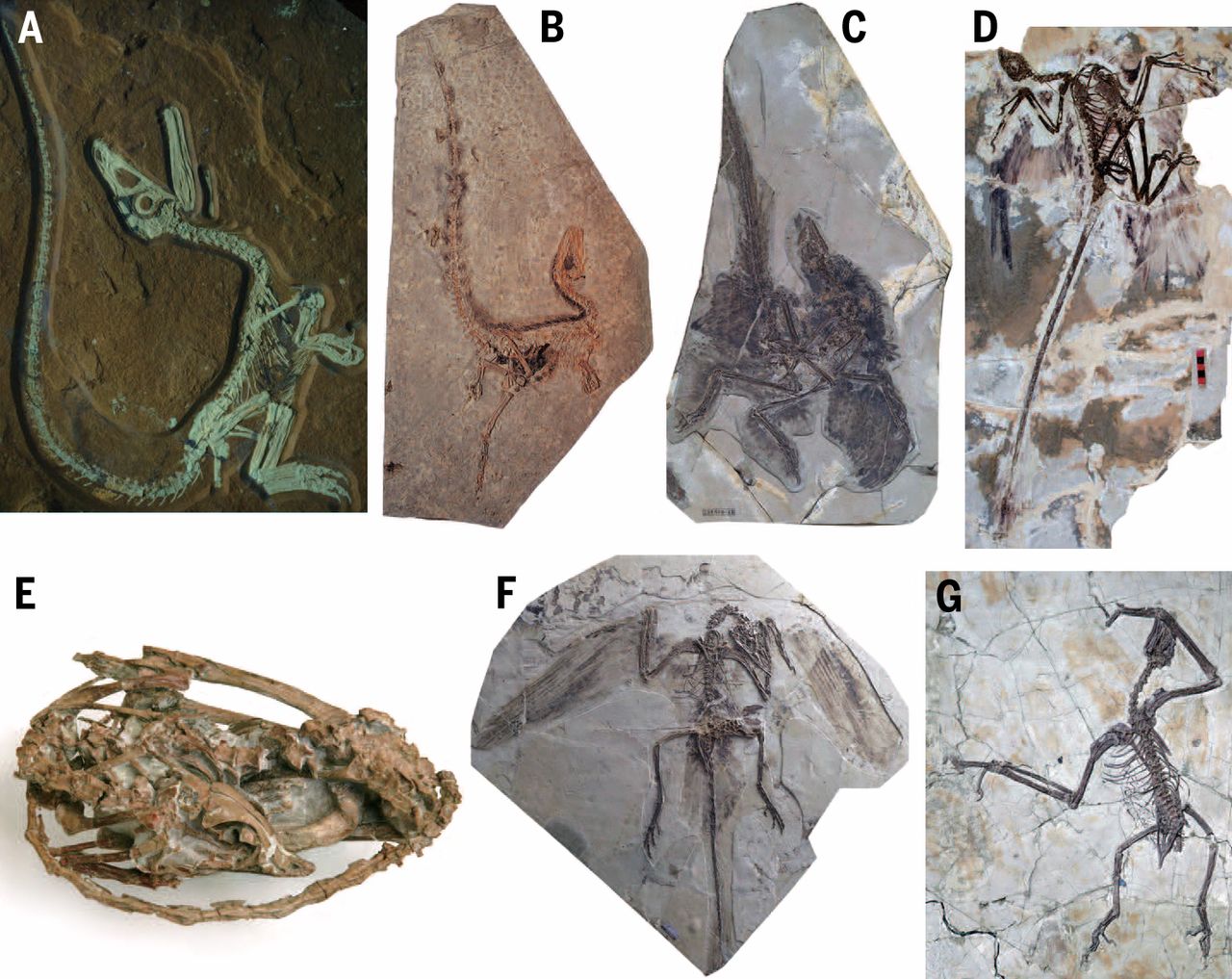

Recent discoveries of spectacular dinosaur fossils overwhelmingly support the hypothesis that birds are descended from maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs, and furthermore, demonstrate that distinctive bird characteristics such as feathers, flight, endothermic physiology, unique strategies for reproduction and growth, and a novel pulmonary system originated among Mesozoic terrestrial dinosaurs. The transition from ground-living to flight-capable theropod dinosaurs now probably represents one of the best-documented major evolutionary transitions in life history. Recent studies in developmental biology and other disciplines provide additional insights into how bird characteristics originated and evolved. The iconic features of extant birds for the most part evolved in a gradual and stepwise fashion throughout archosaur evolution. However, new data also highlight occasional bursts of morphological novelty at certain stages particularly close to the origin of birds and an unavoidable complex, mosaic evolutionary distribution of major bird characteristics on the theropod tree. Research into bird origins provides a premier example of how paleontological and neontological data can interact to reveal the complexity of major innovations, to answer key evolutionary questions, and to lead to new research directions. A better understanding of bird origins requires multifaceted and integrative approaches, yet fossils necessarily provide the final test of any evolutionary model.

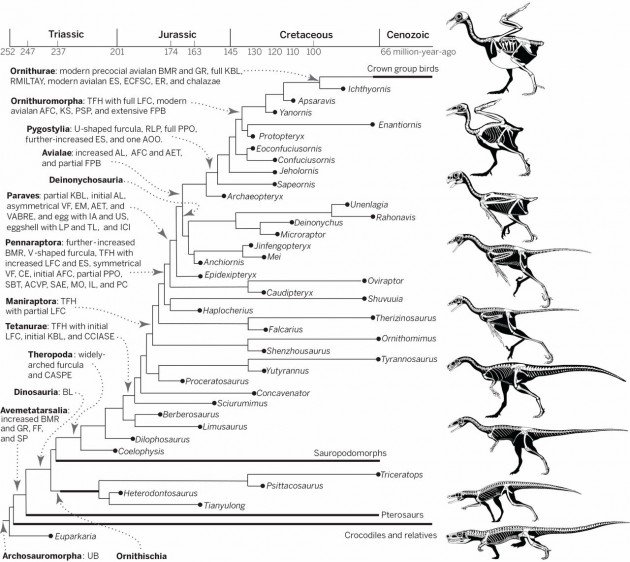

The key figure from the paper:

What I am going to try to do over the next few weeks, when I have time, is to translate the stuff with all the UPPER CASE letters on the left side of that diagram into english, and write it up for you. Clearly, you can see that this review article is looking at all the birdish features and their evolutionary interrelationships. The story is probably too clean. Some dino-bird or another will be discovered, it’s wrist joint will be sideways, and parts of this diagram will be overthrown. Or something. And that will be interesting.

But, as I said above, we are crossing a threshold. The overall pattern depicted here will not change. We understand the evolution of bird flight at more than a basic level. We can describe it, put dates on it, explain it (mostly). We can’t do that with the evolution of any other flight system. Only birds were large enough, bony enough, diverse enough in their moden form, and recent enough to have left enough evidence to do this. Thank you birds.

Are Ostrim and Feducia still holding out as naysayers at this point?

Duncan – based on this symposium at last year’s AOU meeting, I would say the answer is yes, as always:

http://www.birdmeetings.org/aoucossco2014/sessionschedule.asp?SessionID=S14

Wow, we’ve come a long way from Jurassic Park. Looking forward to your posts, this is confusing stuff.

Well, Feduccia seems to be holding on to minimally an agnosticism about theropod origins. I don’t think that applies to Ostrim.