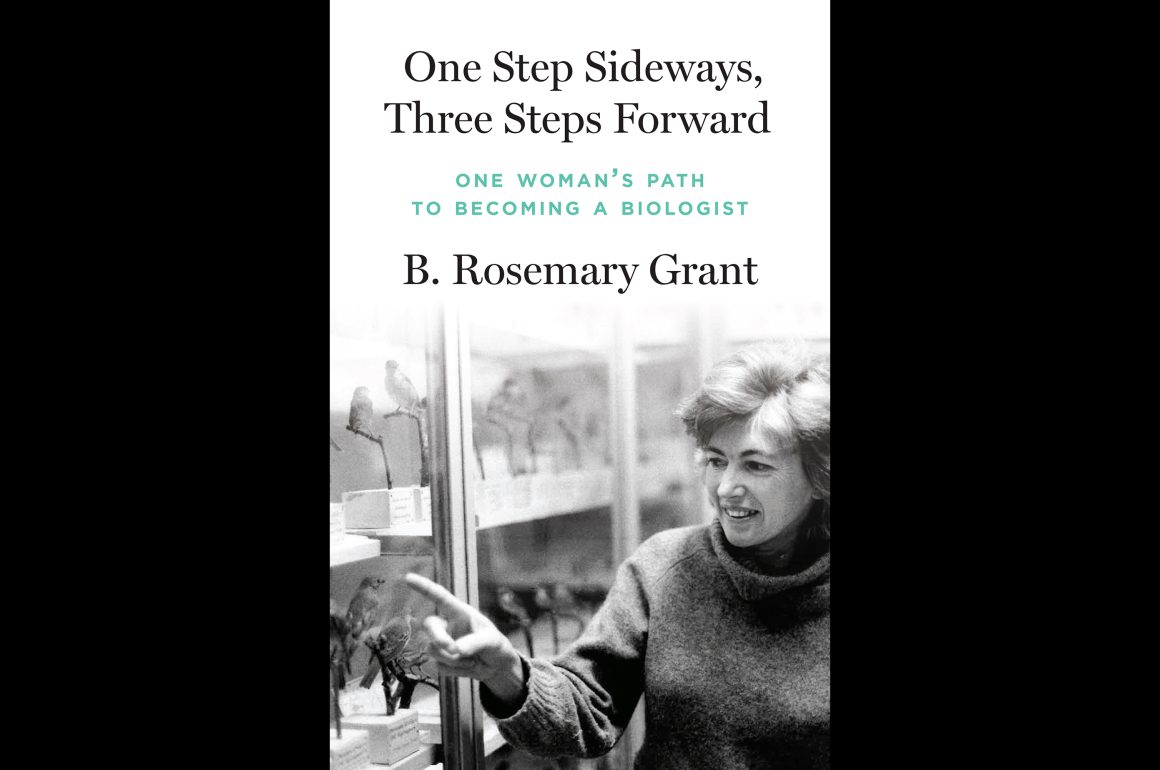

A memoir is a very special type of book, the stories of a life told with a particular goal or from a specific point of view. A good memoir gives insight into unique life journeys, sometimes creative, sometimes emotional, sometimes revolutionary, often inspiring. I was intrigued to read Rosemary Grant’s memoir, One Step Sideways, Three Steps Forward: One Woman’s Path to Becoming a Biologist, because I wanted to know more about the woman who, with her husband Peter Grant, spent 40 years doing research on the Galapagos Islands, proving many facets and greatly expanding on Darwin’s theory of evolution and natural selection in the place where it started. The Grants have been honored and celebrated for their work all over the world, including the Kyoto Prize in 2009 (the Japanese equivalent of the Nobel Prize, which they’d probably also win if there was one for biology) and as the subject of a Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Beak of the Finch by Jonathan Weiner (1995). The latter gives a detailed account of how the Grants lived for several weeks to months on the small island of Daphne with their young daughters, but I wanted more. How does a woman born in 1936 become an evolutionary biologist and nurture a marriage and a family without losing her mind?

One Step Sideways, Three Steps Forward: One Woman’s Path to Becoming a Biologist starts with Grant’s childhood in Arnside, a small village in England’s Lake District, and ends with descriptions of her travels with Peter during a retirement which started in 2008, but which encompasses continuing research and writing as well as hiking through the Tibetan countryside and exploring the indigenous paintings of Kakadu in northern Australia. Though the time span is typical of an ‘autobiography,’ the focus is on experiences and relationships that formed Grant’s interest in biology, the environment, and genetics. Her childhood in Arnside is more than life as a doctor’s daughter in a charming English village, it’s where she learned how to calculate the strength of the area’s tidal bores (twice daily mini tsunamis) based on the gravitation pull of the moon and the direction of the wind. Through her aunt she meets Charlotte Auerbach, a Jewish geneticist who had escaped Nazi Germany and who would later be one of her professors at the University of Edinburgh. In boarding school, a creative and kind teacher influences her to focus on geography rather than history–why memorize people’s names and dates when you could work out the mechanisms of continental drift with paper, crayons, and scissors? Running through these stories is also Grant’s interest in education, and she gives example after example, both from her years as a student and as a middle-school teacher and later university professor, of how children’s and young people’s interest and curiosity are sparked by questions and projects that challenge.

For me, the most compelling parts of Grant’s life are how she overcame barriers to women’s education and scientific careers (actually, careers in general) during the 1950’s and 1960’s. It says a lot about Grant’s personality that she never presents obstacles as revolutionary conflicts or in a context of extreme anger and frustration, though she clearly was angry and frustrated at times. They are problems to be solved through strength of will, creative thinking, and, I think, an optimistic, no-nonsense outlook. Her father did not approve of higher education for women. She wore him and school officials down by “defiant argument,” declaring she would rather study biology than marry (p. 53), finding a way to take the university entrance exams even when waylaid with a serious case of mumps. After she and Peter Grant marry, they face dilemmas common to young academic couples, especially those with limited financial resources: who will get the Ph.D.? Who will work? When will we start a family? Not unexpectedly, Peter finishes his Ph.D. program at the University of British Columbia (Rosemary accompanies him to the Tres Marías Islands to help with his research on the biological evolution of island and mainland birds) , does a post-doc at Yale, and starts a tenure-track position at McGill University while Rosemary teaches, works as a research assistant for various professors, and takes care of their family of two girls, Nicola and Thalia. She often holds down three jobs, including the child care as her most important one.

It isn’t till 1985, 21 years after Peter has achieved doctoral status, that Rosemary gets her Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from Uppsala University. Her doctoral thesis is comprised of articles she has already written on research she has already done and is in the process of writing–a rather backwards way to do it, but Rosemary is clearly delighted and shows no regrets that this credential was so long in coming. As the title of the memoir says, “one step sideways, three steps forward.” She emphasizes throughout her narrative that her eye was always on the prize, though it seems like the goal of a Ph.D. gradually gave way to the joy of doing research with her husband and family, and sometimes had to find creative ways to step forward. As a young working mother, for example, she gets Peter to agree to hiring a babysitter every Monday morning so she could go to the university library and read scientific journals, a morning that becomes known as “Rosemary’s Mondays.” This may not seem very out of the ordinary to today’s grad student, but I know from experience that it was, and it clearly was inspirational to other young women who she talked to later in life. Throughout the book and in interviews, Rosemary describes Peter as unwavering in his support for her scientific career goals and research, and I think you have to have lived in that period to understand how unique this was. The part of me that loves soap opera kept waiting for conflict–fights, declarations of women’s liberation, screeds about oppression. But no, this is a tale of communication, partnership, and mutual respect and affection, not of STEM politics. Rosemary even points out that her scientific career has been helped by men as well as women, sometimes more, commenting on the ‘Queen Bee’ syndrome that used to be prevalent in all occupational spheres.

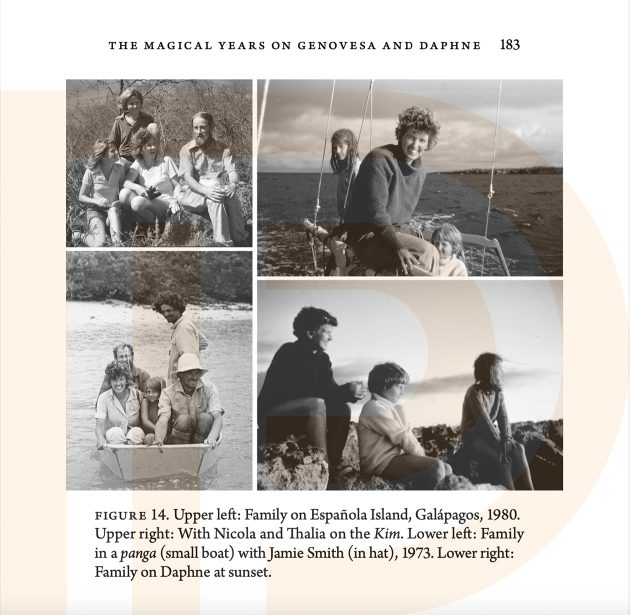

© 2024, Princeton University Press. Screenshot of photos of the Grant family at the Galapagos, from p. 183. (The large P in the background is because I used an advance PDF kindly sent by PUP, the actual published books, in paper & ebook format, do not have it.)

The Grants work on the finches of the Galapagos takes center stage in chapters 15, 16, and 17. Rosemary describes in detail the origins of this research project, which started out as a two-year study and ended up lasting 40 years; summarizes the directions of the research took on the islands of Daphne Major and Genovesa–questions asked, data collected, effect of extreme weather conditions, names of their many collaborators, the groundbreaking discoveries made once they were able to use genetic analysis; recounts the major findings of their research, the unexpected insights, the actual witnessing of evolution in process; and, in my favorite chapter, talks about “The Magical Years as a Family on Genovesa and Daphne.”

For ten years, starting in 1973, the Grants lived on the Galapagos Islands, mostly Daphne, for several weeks to several months a year. The kitchen was in a cave, fresh water was brought to the island with them and carefully measured out, the children (eight and six years old when the trips start) were home-schooled and enthusiastically did their own research on the natural wonders of the island–mockingbirds, doves, fiddler crabs–which was published, bathing was done in sea till Peter was almost attacked by a shark, after which they limited themselves to buckets (apparently the Whitetip Reef Shark was deterred by the shampoo Peter was using, which had the same ingredients as shark repellant). Again, my soap opera instincts flare out–this can’t be as idyllic as it sounds! And as if she hears me, Rosemary offers Nicola and Thalia’s own descriptions of their childhoods. Most enthralling is an excerpt from a letter Nicola wrote to writer Joel Achenbach in 2014: “Quite simply, it was magical. I don’t know if you have been to the Galapagos Islands, but for me they are like what the Celts call “thin places”–places where the veil between heaven and earth is frayed. My sister and I were very lucky to be able to spend a few months each year there….I don’t remember ever being bored.” (pp. 189-190, also Appendix B). I would love to see a film or TV series based on these “magical years,” but of course it could never be dramatized correctly because of the absence of conflict, only a healthy, athletic, intelligent family engaged in groundbreaking research.

The last parts of the memoir, as I said earlier, are devoted to the Grants’ travels to Nepal, South America, Asia, Australia, Europe, often to participate in symposia or receive awards, also to vigorously hike and visit exceptional natural and historic sights, making lifelong friends with hosts and guides. Rosemary’s keen observations are filtered through her analytical eye; in Nepal, for example, she compares the social networks of the local mountain people to those of the mountain villages in Switzerland, asking why one is obviously organized to prevent inbreeding and the other (the Swiss) encourages it. She uses these pages to write about indigenous people in various lands, a lifelong interest. In Ecuador, in 1991, Rosemary, Peter and their girls live with the Siona, a hunter-gather group, in the Ecuadorian Amazon, witnessing their transition from hunter-gather to an agricultural way of life. In Australia, decades later, Rosemary and Peter get to know students of indigenous heritage from New Guinea and Australia who are attending classes at Charles Darwin University, where they are visiting scholars. In both cases, Rosemary points out the precariousness of these peoples’ lives, shrinking biodiversity and intrusions by capitalist development in the Amazon (and elsewhere), the recent political defeats of indigenous peoples in Australia. She sees them as examples of life we should emulate, learning to live within the limits of our local resources in harmony with nature.

One Step Sideways, Three Steps Forward has three things that I think really enhance any book–illustrations, notes, and a comprehensive index. The black-and-white photos scattered throughout the text show both the people and the habitats of Rosemary’s life: from the estuary and viaduct of Arnside to the lava cliffs of Daphne to the houses of the Siona people; from parents and brothers to early married life and young children, to enjoying retirement in Princeton. The Notes section carefully annotate each chapter, giving full citations for scientific articles by the Grants and their colleagues and other books and articles mentioned in the text. The section is preceded by three Appendixes: “We Are Not All the Same,” a follow-up on the life paths taken by Rosemary’s two brothers; “Nicola’s Letter to Joel Achenbach, 2014,” the full text of the letter cited in the text (very enjoyable); and a listing of “Honors and Awards, with Some Comments.” a section that is more than it seems with Rosemary’s comments on what each honor means to her. This isn’t an award ticker, these are the comments of a thoughtful woman who appreciates her place in the hierarchy of the sciences, knows it was justly earned, and who enjoys passing her and her partner’s legacy on to younger generations in the form of an award named for her, the Rosemary Grant Advanced Award, a monetary prize given to PhD students by the Society for the Study of Evolution.

One Step Sideways, Three Steps Forward: One Woman’s Path to Becoming a Biologist is Rosemary Grant’s story, the memoir of a woman who has lived a life of scientific adventure (which is what I call living on a volcanic island with no electricity) and family commitment. It’s a unique life, and her narrative reflects a consciousness that although no woman will be able to follow in her footsteps exactly, a passion for science and a willingness to find creative solutions to work-life conflicts will present similar paths to women today. I don’t know. Today’s world presents more opportunities for women, but science itself is being discredited. It’s a different world from even a year ago, when Grant wrote her final chapter, “Where Do We Go From Here?,” encouraging the implementation of international plans to address biodiversity loss, protection of indigenous people’s rights, and reverse the direction of climate change. Still, I don’t think Rosemary Grant would see these events as obstacles, only more challenges in a world of genetic and environmental change.

It’s been a prolific two years for the Grants. One Step Sideways, Three Steps Forward was published a year after Peter Grant’s own memoir, Enchanted by Daphne: The Life of an Evolutionary Naturalist (PUP, 2023) and the same year as a new edition of the couple’s classic account of their research, 40 Years of Evolution: Darwin’s Finches on Daphne Major Island (PUP, 2024). Though I haven’t read either book yet, I probably will in the future; they are all a piece of a complex landscape of science, natural beauty and wonder, and very smart people. For now, I have my enjoyment of Rosemary Grant’s warmly written narrative about a life lived with curiosity, analytic intelligence, and a deep thoughtfulness and respect for both the people within one’s life circle and beyond.

©2011 Donna L. Schulman; Genovesa Cactus-Finch, female (Geospiza propinqua) and Small Ground-Finch, female (Geospiza fuliginosa), taken on my trip to the Galapagos in 2011. At the time these photos were taken, Genovesa Cactus-Finch was considered a subspecies of Common Cactus-Finch. Rosemary Grant original goal was to study speciation through research on what was then the Large Cactus-Finch on Genovesa. Small Ground-Finch was a rare migrant to Daphne, where it sometimes bred with Medium Ground-Finch. Its genes were found to be part of the genetic make-up of Common Cactus-Finch through this hybridization, since although Common Cactus-Finch did not breed with Small Ground-Finch, it did breed with Medium Ground-Finch.

One Step Sideways, Three Steps Forward: One Woman’s Path to Becoming a Biologist

by B. Rosemary Grant

Princeton Univ. Press, June 2024 (U.K. July 2024)

328 pages, 21 black-&-white illustrations

ISBN: 9780691260594

$29.95; eBook discount when purchased directly from PUP

Leave a Comment