The Peterson Field Guide to Bird Sounds of Eastern North America by Nathan Pieplow is innovative, fascinating, and challenging. As the title plainly says, this is a guide to the sounds birds create—their songs, calls, chatters, chitters, barks, drills, raps, claps, pops; some made with syrinx (a bird’s vocal organ), some with bills, wings, feathers, feet, or air sacs (it seems that there is not a body part that some bird doesn’t use to make sound). The guide covers 520 species of birds regularly found in the eastern United States and southeastern Canada, including, interestingly, a number of exotic species. Rather than the bird photos or drawings we expect in a field guide, the species accounts are focused on spectrograms, visual representations of sound frequencies, illustrating each species’ unique sounds in black-and-white squiggles and lines (though there are drawings of birds as well). Here is the challenging part: how do we utilize this guide to identify birds in the field? As a birder who struggles to hear and identify bird sound, this is the question continually on my mind as I write about this book.

But, first the basics. The Peterson Field Guide to Bird Sounds of Eastern North America is divided into three main sections: Introduction, Species Accounts, and Index to Bird Sounds (also called the Visual Index). There is also a traditional index to bird species, by common and scientific name. And, beyond the book itself, there is an audio component, a web site that allows you to play every spectrogram in the book.

A lot of thought has gone into the design of this guide. The front inside cover offer “How To” diagrams to Species Accounts, Audio Files, and the Visual Index. The inside back cover section, “What Did You Hear?” serves as a quick entry point to the Visual Index; types of bird sounds are listed under categories (‘A Single Note,’ ‘The Same Note Repeated,’ ‘A Long Complex Song,’ etc.), directing you to appropriate pages in the Index. Each section of the book, and each category of the Visual Index, is differentiated by colored bars on the bottom of the page. Full-page photographs of birds divide major sections. The guide itself is sized and bound like the other titles in the Peterson’s Field Guide series, complete with flexicover.

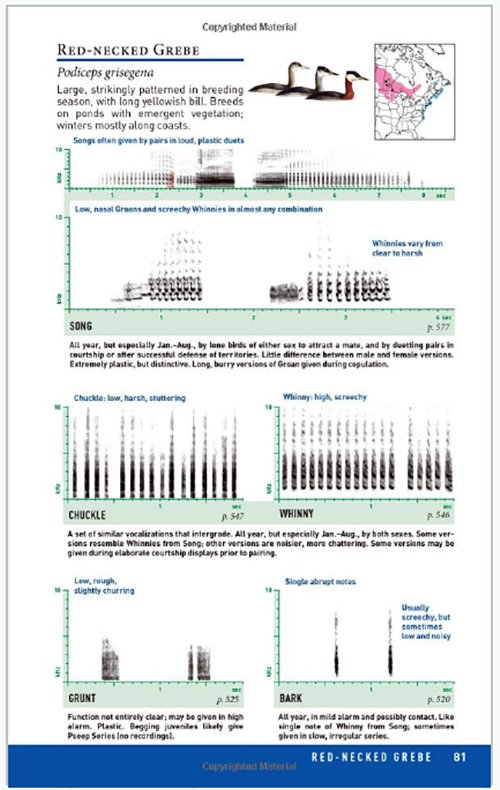

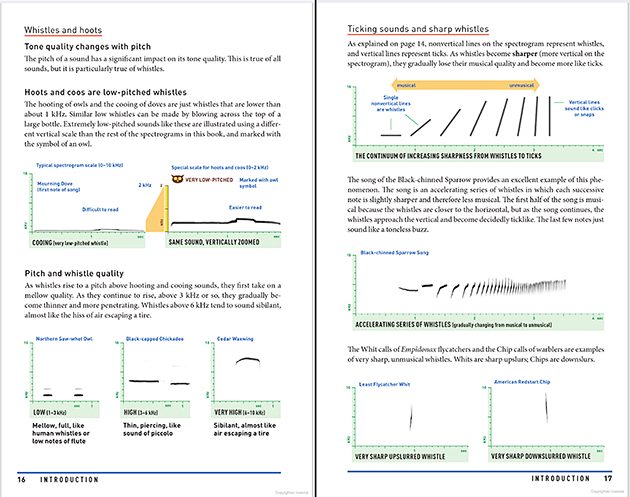

The excellent Introduction gives background on how birds produce sound, how sounds are presented visually, how to “read” a spectrogram, the naming of bird sounds, and the biology of bird sounds, and how bird sounds are recorded and spectrograms created. Yes, if you are going to use this book, you must read the Introduction! It’s only 33 pages, and Pieplow has a talent for making this topic, which could be intimidatingly complex to the newcomer, simple and accessible. Also, you have the option of reading the Introduction online, on the book’s website, which allows you to hear the sounds being cited.

Species Accounts are arranged taxonomically, grouped by family. It is unclear which taxonomy is being followed here; it appears to be loosely based on the American Birding Association July 2016 checklist (based on AOU taxonomy) with a few switches in family order (Verdin after Bushtit, for example) and some rearrangements of species; in both cases, I think the idea is to rearrange the space to allow for longer descriptions or to position similar species next to each other. There is no table of contents to the Species Accounts, the only thing missing from this otherwise well-designed field guide, which is why taxonomic order becomes important. Knowing the order allows us to know where to find the species. (Of course, there is always the index, but that’s an extra step.)

Family sections start with a brief description of the characteristics shared by the species in the family, followed by a description of the sounds made by those species and how they obtain their song/call knowledge. These sound descriptions are brief, one to three paragraphs, but are expanded for certain species. Woodpeckers, appropriately, get a whole page on drumming and tapping. A special box shows the differences amongst hawk and eagle copulation sounds. And, under Finches, Pieplow outlines some of the challenges involved in identifying the complex finch and Red Crossbill vocalizations.

Each Species Account includes one to three drawings of the bird, a range map, common and scientific names, and a one to three sentence description of the bird, which may or may not include its migratory and breeding habits, feeding behavior, plumage, habitat, and demographic status—whatever helps identify the bird quickly. I really appreciate the inclusion of this material, which means the user does not necessarily have to hold the bird song field guide in one hand and the bird field guide (or app) in the other. Most of the artwork and range maps are from Peterson’s Field Guide to Birds; credits are given in the back of the book.

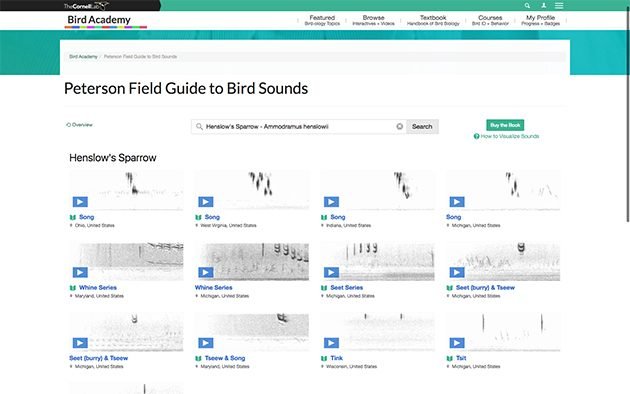

The focus of the species account is, of course, vocalization: spectrograms of the species’ various sounds. And, text that describes and expands on this graphic information. The number of spectrograms per species varies, and it’s fascinating to see the variety of number of vocalizations for each species. There are surprises, especially if you are not a natural “earbirder.” I expected Blue Jay to have many different vocalizations and they do, two pages worth, in fact: jeer, pumphandle calls (highly variable, 6 different examples), quiet song, rattle, keer, vrit, and 3 spectrograms of just some of their bird imitations. But, I didn’t expect that Henslow’s Sparrow would have a page-full repertory of sounds: Song (3 different types), Whine series, Seet series, Seet and Tseew night calls, Tink calls and Tsit calls.

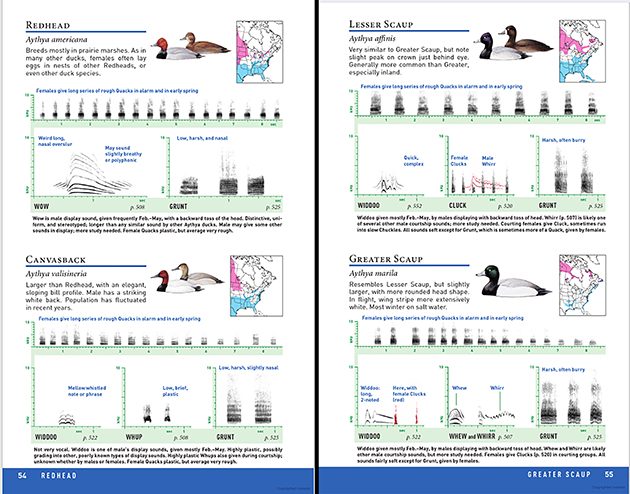

Another surprise is how useful the spectrograms can be in helping to differentiate between similar looking birds–take a look at the differences between Lesser Scaup and Greater Scaup in the image above. (Of course, this only works when the target birds vocalize, which Scaup don’t tend to do in winter in New York City. I do see, however, much study of the Empidomax flycatcher pages in my future.)

The text for each spectrograph describes when and where the sound is used and the degree of variation. Redhead’s Wow sound, for example, is noted within the spectrograph to be “weird long, nasal overslur” and sounding “slightly breathy of polyphonic.” The caption notes that it is a male display sound, given frequently February to May, “with a backward toss of the head,” longer than similar sounds by other Aythya ducks.

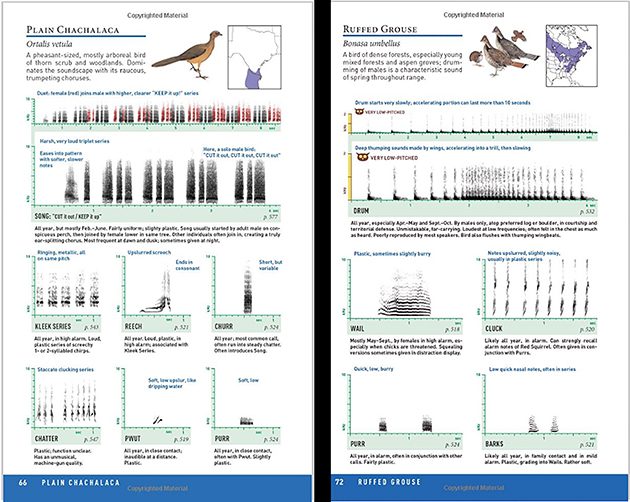

One of Pieplow’s achievements is the incredible variety of names he gives to bird sounds. Adding to the sounds I listed in the first paragraph, there are contact calls, flight calls, whine series, groans, interaction calls, first-category song, second-category song, tinks, chups, burrts, rattles, chortles, yoy-kips, flutters, purrs, coos shrieks, wails, hoo-wahs, squee-squeeps—there’s not enough space to type them all! I found the spectrograms of birds with unusual sound patterns particularly intriguing. The pages below show Plain Chachalaca engaging in a male/female duet (the female sounds are in red), and the drumming and thumping sounds Ruffed Grouse make with their wings. The small owl-face icons indicate sounds that are particularly low in pitch.

Each spectrogram includes a page reference to the sound in the Index of Bird Sounds, allowing us to see what bird sounds are similar to those of the target bird. The Redhead’s Wow, for example, is listed under the heading ‘A Low-Pitched Note,’ part of the large Index section, ‘A Single-note Sound.’ The Wow is unique, only produced by Redheads. It is longer than Wheew (Wood Duck, Northern Pintail) and more nasal than Whoop (Tundra and Mute Swan), two of the other sounds listed as low-pitched notes.

Unlike the Introduction, Species Accounts are not reprinted with audio on the book website. (This makes sense, since the website is available to the public.) Instead, we search the site to retrieve a roster of audio files–all the files illustrated in the book and more. Over 5,400 audio files are available, many edited to improve quality. Each audio file gives name of recordist, place of recording, and date. I find it interesting that this part of the book’s website is hosted by the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology Bird Academy, while the Introduction’s web component is part of Nathan Pieplow’s personal website, Earbirding. I hope both components continue to be “live” as they are valuable parts of the field guide. And, I hope an eBook version that will allow us to read the Species Accounts and play the audio, or an app, or both, are being planned for the future.

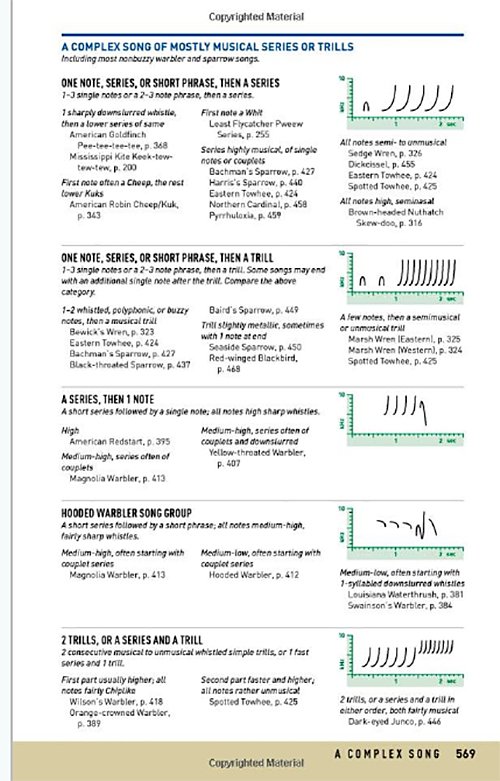

The last section of the book, the Index to Bird Sounds, also called the Visual Index, is the most creative part of the Peterson Field Guide to Bird Sounds of Eastern North America, and, I think, the section that requires the most work, especially for sound-challenged birders like me. The Index lists all sounds displayed in the Species Accounts, grouping similar sounds together. There are seven major parts, and each of these parts is subdivided by sound characteristic, tone quality, and pitch quality. The page below, for example, is A Complex Song of Mostly Musical Series or Trills, part of Index Part VII: A Complex Song. It includes sounds made by American Goldfinch, Bachman’s Sparrow, Hooded Warbler, Magnolia Warbler, and Red-winged Blackbird. The page number of the species account for each bird is listed next to the name. The symbol on the right indicates roughly how the sounds in each group appears on the spectrogram. It sounds confusing, and, like many new things, it is confusing until you start using it.

Pieplow lists two methods for identifying bird sound using the Index, one starting with the Quick Index on the inside back cover, and the second starting with looking up the species account for a familiar bird that sounds similar. I found both a little awkward to use, mainly because I don’t have the auditory skills to distinguish pitch and tone, or, for example, to know ‘a complex song with mostly musical series’ from ‘a complex song with musical warbles.’ I also lack an auditory vocabulary; I’m not sure what distinguishes a harsh note from a burry note from a buzzy note. The good news is that this book offers resources for learning. The bad news is that it will take time and hard work. Or, maybe that is good news too?

On a recent trip to see a Henslow’s Sparrow at the Shawangunk Grasslands NWR, New York State, I prepared by reviewing species accounts in my traditional field guides. I then took the additional step of looking up the species in Pieplow–studying the spectrograms while playing the corresponding sounds. I was worried that every birder in New York State had already seen the sparrow and I would have to find it all by myself, so learning these songs and tinks and tsits was essential. I could have played the audio on my Sibley’s app over and over, but that process seldom works for me. I am a visual learner, and seeing those spectrograms cemented the sounds in my head. As it turned out, there were birders who “had” the bird by the time I got there. But, hearing that Henslow’s Sparrow do its short, “tinkling, semimusical” song was thrilling because I KNEW it. Those extra 20 minutes paid off big time for me in terms of knowledgeably observing and appreciating the bird.

I find it comforting that author Nathan Pieplow says he is not the best ‘earbirder’ in the world, and that this book is one of the resources he has developed to help him learn bird sound. In ‘real life,’ Pieplow is an instructor at the University of Colorado, where he teaches writing and rhetoric. He has studied bird sound since 2003, and his Earbirding website (co-owned with Andrew Spencer) has blog posts dating back to 2009. The posts are on diverse aspects of bird sound, from recording equipment and techniques to taxonomy to identification to hearing loss (human, not bird), and make an entertaining complement to the field guide. So is Pieplow’s contribution to the 2017 anthology Good Birders Still Don’t Wear White. You can hear a lot more about Pieplow and the background of the Field Guide to Bird Sounds in his lively interview with Nate Swick for the ABA Podcast series.

The Peterson Field Guide to Bird Sounds of Eastern North America is an ambitious, innovative advance in bird identification, auditory reference, and field guide design. Using it requires thought, analysis, and work. Spectrograms are not new to the birding field guide. Chandler S. Robbins used them in a more primitive form in 1966 in the Golden Field Guide Birds of North America. And, they are an integral part of Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle’s The Warbler Guide (2013), another innovative field guide. Pieplow has here expanded the scope and raised the bar, making the spectrogram THE core of the field guide. He has developed a new vocabulary for describing bird sound and new processes for sound identification. I can’t think of a birder whose knowledge base and birding skills would not be improved by using this book. Those who bird almost purely by ear will delight in seeing their beloved trills graphically portrayed and will enjoy examining the finer details of alternate warbler songs. Those, like me, who are sound challenged, will at last be able to learn to hear by seeing. And beginning birders will have the option to learn an auditory process for bird identification in parallel with traditional visual methods. I am happily looking forward to the Peterson Field Guide to Bird Sounds of Western North America and, after that, guides to the bird sounds of the rest of the world. Nathan Pieplow has a lot of work ahead of him (work I hope he will enjoy), and hopefully, so do future developers and writers and recorders of our field guides.

Peterson Field Guide to Bird Sounds of Eastern North America

by Nathan Pieplow

Peterson Field Guide series

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, March 2017, 608 pages, 5 x 1.2 x 8 inches

ISBN-10: 0547905580; ISBN-13: 978-0547905587

$28.00 (discounts available from the usual suspects)

Leave a Comment