The April arrival of the Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America, Second Edition was a supremely happy moment in a very difficult, sad month. Seeing Peterson’s classic illustrations with their pristine lines and arrows in an updated format, ready for birding as soon as the birds arrived and I could leave my apartment, was beyond comforting, it meant there was still stability and continuity amidst the chaos.

A Little Bit of Field Guide History

The Peterson Field Guide to the Birds of Eastern and Central North America was my first field guide, part of an ‘introduction to birding’ workshop taught by the incomparable Starr Saphir. That was the fourth edition, dated 1980, and I didn’t realize at the time that we were getting the books for free because the fifth edition had just been published. (I was what could be called a ‘field guide virgin’ at the time.) I had heard of Roger Tory Peterson, but I didn’t know that he was a New York birder, born in upstate Jamestown in 1908, nor that he had birded the Bronx when he was a young man, a member of NYC Linnaean Society and the fabled Bronx Bird Club. And, because his name was so firmly a part of birding culture, I also didn’t realize how recently he had lived and birded the United States, nor how relatively new was the concept of a field guide.

A Field Guide to the Birds: Giving Field Marks of All Species Found in Eastern North America was published in 1934 by Houghton Mifflin (note–Peterson was 26 years old), after being rejected by four publishers. The story is that an HM editor was also president of Massachusetts Audubon. It was not the first field guide to birds ever published (shoutout to Florence Merriam Bailey, whose Birds Through an Opera-Glass–published in 1889, when she too was 26–is considered the first birding guide to focus on field observation as opposed to dead bird observation), but its small size, organization, and focus on selected identification marks resounded mightily with the public, and the printing run of 2,000 copies sold out in two weeks.*

A Field Guide to the Birds eventually became Peterson Field Guide to the Birds of Eastern and Central North America, in its fifth, totally revised edition; the seventh edition will be published this October. A companion regional guide, Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Western North America was published in 1941; its fifth edition will be coming out in early September. Interestingly, the field guide I’m looking at today, the larger field guide covering all of North America, was not published until 2008, the year Peterson would have been 100 years old. Peterson died in 1996, but Houghton Mifflin Harcourt and the Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural History have continued his work, and the larger edition drew on materials from earlier guides and updated text and images. **

What Is In This Field Guide?

The Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America, Second Edition covers 807 species in the United States and Canada (like most field guides labelled ‘North America, it doesn’t include Mexico and Central America). Plus, in a major expansion, the birds of Hawaii, the most recent geographical addition to the American Birding Association Checklist. Adding the 76 new species in the Hawaii section, this makes coverage of approximately 884 species. I say ‘approximately’ because I may have counted incorrectly, and because some species–little seen exotics and vagrants–are covered less well than resident, migrant, and more common exotic birds. Extinct birds, such as Ivory-billed Woodpecker, are included. In fact, there is a whole, sad page depicting 11 out of the 33 extinct Hawaiian birds, representing “the greatest loss of avian diversity in the world” (p. 456).

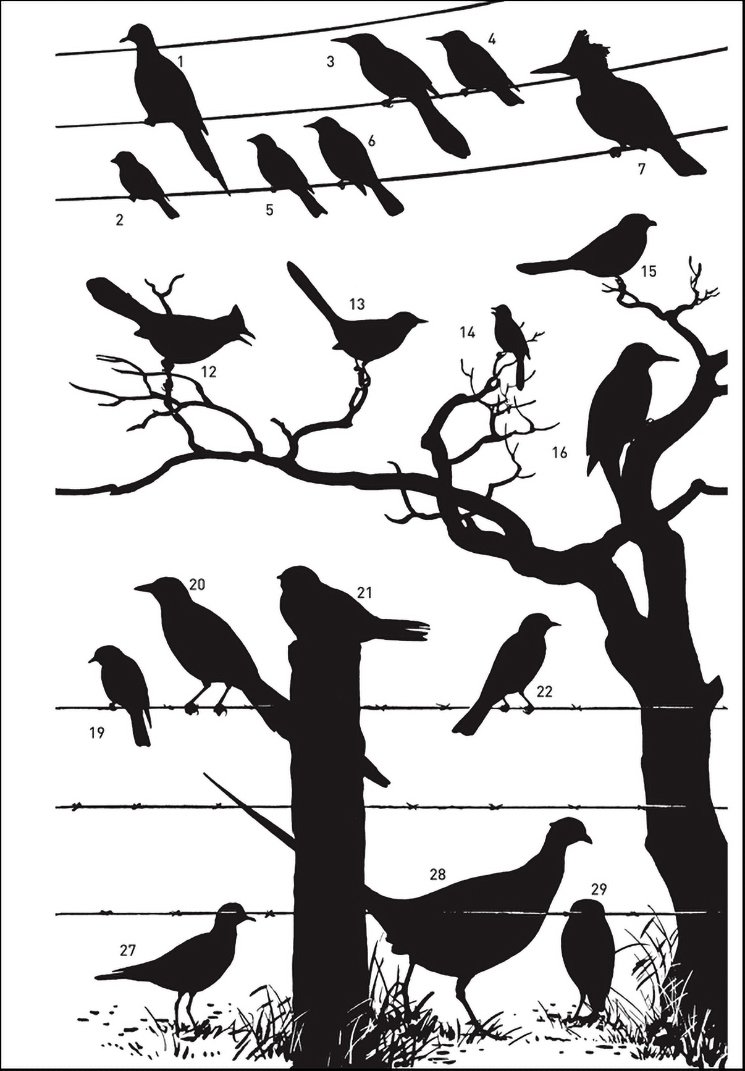

The guide is divided into 3 main parts: An Introduction, which explains the basics of identifying birds, and how to use the range maps and habitat information in the species accounts to find and identify birds; ‘Plates’ or species accounts; and back-of-the-book materials–Checklist of the American Birding Association (current as of September 2019), printed in a format that allows you to write in the dates of your Life Birds, Photo Credits, and indexes–detailed and one-page. The guide ends with the famous Peterson bird silhouettes. Long time 10,000 Birds readers might remember that the silhouette pages are amongst Mike Bergin’s favorite features in the Peterson guides, “exquisite shadow plays of birds at the shore, in flight, or loafing along a roadside.” They’re also good exercises for practicing holistic birding–identifying birds by shape, size, and structure (all you need to do is place your hand over the box with the bird names; can you tell the Robin from the Bluebird?).

Other key organizational features include map legends on the inside front and back covers (front for the range maps, back for the more specialized Hawaiian maps, which track seabird species). The requisite bird topography diagrams, showing the anatomical parts of a songbird and a wing, are placed opposite the title page. And, the One-page Index, a quick reference to locating major bird families, is placed in two locations–the front and the back of the book. I don’t think I’ve ever seen this before! This means that all your basic reference information, the pages you need to consult to find a bird or figure out how to read its description, can be reached by browsing fingers immediately, in less time than it would take to type a question into Google. I love a field guide that makes usability a priority.

Species Accounts

Species accounts are organized in sequences which emphasize the grouping together of similar looking birds in similar habitats, a system started by Peterson and codified by Steve Howell and colleagues in the article “The Purpose of Field Guides: Taxonomy vs. Utility?” (Birding, November 2009). The article, which motivated a lot of discussion at the time, states: (1) organization by a specific taxonomic system is confusing to birders since birders are trying to identify a bird and taxonomists are attempting to map out evolutionary relationships, and (2) taxonomic systems are changing with rapid and dizzying speed and different systems adopt sometimes wildly variant sequences, making field guide editors and birders crazy (not Howell’s exact words, but the gist, I believe).

Howell and colleagues propose a standard sequence of species for field guides based on eight groupings–swimming waterbirds that swim, flying waterbirds, walking waterbirds, upland gamebirds, raptors, miscellaneous larger landbirds, aerial landbirds, and songbirds. When you review the system, it makes perfect sense: falcons are placed with hawks, nightjars are next to owls, and grebes are close to ducks, rather than separated from them by quail and grouse. It also makes me, personally, approach the guide with some skepticism. I like field guides based on taxonomic systems, probably because I’ve been trained to work with obscure classificatory systems. Then again, try explaining to a new birder why falcons come after woodpeckers and before parrots!

Species Accounts names and species have been updated to all changes up to the 2019 American Ornithological Society Supplement. Blue-throated Hummingbird is now Blue-throated Mountain-gem; Common Ground-Dove is Common Ground Dove; and Cassia Crossbill has been added, amongst other updates. Major subspecies are presented–“Myrtle” and “Audubon’s” forms of Yellow-rumped Warbler, the five forms of Dark-eyed Junco, etc.–but birders will get more comprehensive information in other field guides, particularly National Geographic and Stokes.

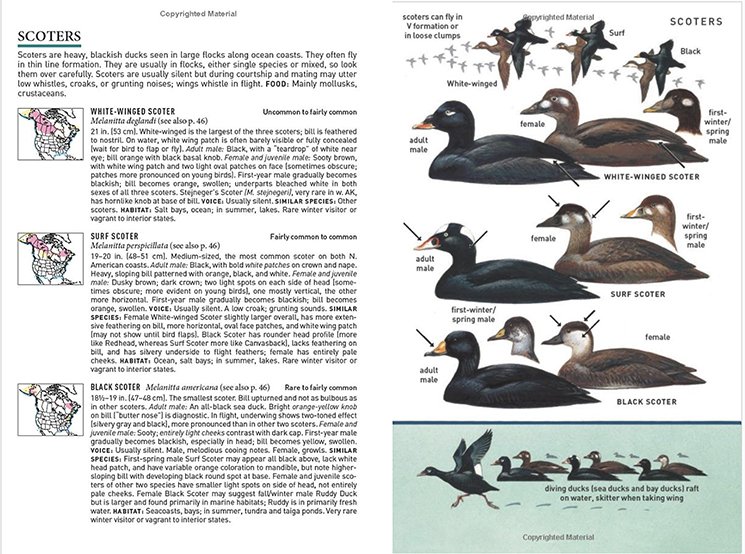

The Accounts present text on the left and images on the right. Family groups are briefly introduced with descriptions of their shared characteristics. The text pages have a lively look. The designers have made good use of fonts (a very large size for family group names, bolded letters for species names and subtopics), color coding (colored bands at the bottom of each text page denote different bird families), and colored range maps. Each species account includes common name; scientific name; abundance (uncommon, scarce, etc.); measurements; a brief physical description that emphasizes easy-to-see field marks (marked by italic font) and also sometimes behavioral clues; voice (transcription of call and/or song); similar species and how to tell them apart; and habitat. Descriptions are more extensive for species that are sexually dimorphic, or have seasonally different plumage, or young with differing plumage. Writing is direct, to the point, and uses as little technical language as possible; a waterthrush’s supercilium, for example, is an “eyebrow strip.”

Paul Lehman (data work) and Larry Rosche (graphic presentation) updated the distribution maps.*** The maps are small and not always easy to read, especially if they contain the colored dash lines for summer, irregular winter, year-round, and migration ranges. The first edition of this title had larger versions of the maps in a section in the back. This was a lengthy section, 88 pages, and I imagine it was eliminated to make room for the Hawaii section and to create a more compact, lighter volume.

Artwork is classic Peterson–slightly simplified images of birds in profile, with arrows pointing to significant field marks described in the text. Peterson is widely praised and criticized for his “schematic” reductions of birds, and it’s important to understand that his goal was to educate. In that sense, the term “schematic,” defined by the Cambridge Dictionary as “showing the main form and features of something, usually in the form of a drawing, which helps people understand it,” is high praise.

It has also common these days to criticize those classic arrows, pointing to barred underparts or a light eye or a very large bill. I like the arrows! The thinking behind the criticism is that the arrows reduce bird identification to a matching game in which the birder focuses on details of bill size or the shape of an eyebrow stripe instead of considering a bigger picture–habitat, abundance in a specific location, migration patterns, vagrancy tendencies–and ‘jizz’–size, shape, and structure of the bird. This can happen, especially with new birders. I remember the days when I didn’t understand migration and the fact that you could see Hooded Mergansers in fall and winter but not in summer. But, the fact is that a Peterson field guide is more than arrows and distinctive field marks and the text does specify habitat and illustrate migration patterns and distribution. And, the ‘schematic’ bird images, with similar-looking birds grouped comparatively on each plate, actually encourage analysis in terms of shape and structure. Perhaps it’s up to the more experienced birders, the mentors and guides, to encourage new birders to use the whole guide, not just the arrows. And, of course, to read the introduction.

Bird artist Michael DiGiorgio has done an incredible job creating the images for the Hawaii section and ‘tweaking’ some of Peterson’s original artwork, using modern technology. If you take a look at DiGiorgio’s own bird art on his web page, you can appreciate his expert adaptation of Peterson’s style.

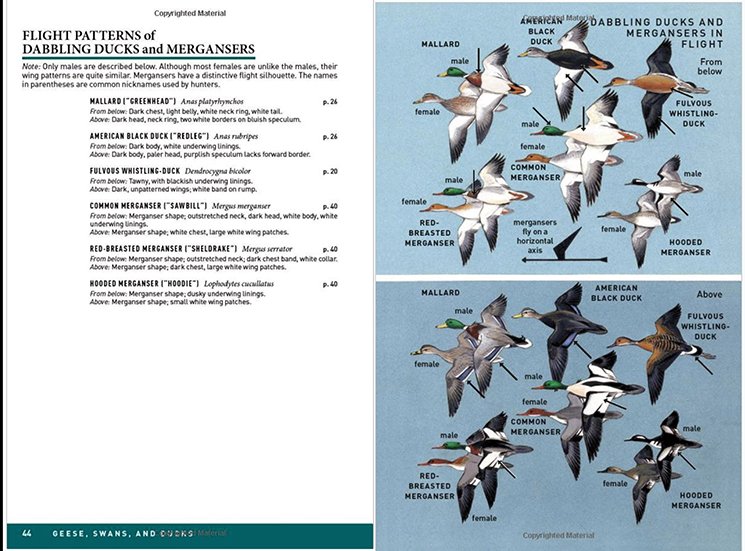

The groupings of the images on each plate can strike the eye as graceful (loons, warblers) or jumbled (banded plovers, woodpeckers). It sometimes seems like the page is just bursting with images, so many forms of a Black-bellied Plover (spring/summer, fall/winter, juvenile, in flight) or an American Three-toed Woodpecker (female, Rockies male, northern male) to present. Small images accompany many of the larger bird images–the bird in flight, juvenile form, breeding plumage–and there are separate plates for first-year and second-year gulls and for hawks as they look in flight, from below. There are also the familiar layouts that have become famous, even beloved–Empidonax Flycatchers in a five-part wheel, Acadian, Yellow-breasted, Willow, and Alder circling Least; Flight Patterns of Dabbling and Diving Ducks; Selected Fall Warblers (when did they stop being Confusing Fall Warblers? I loved that page title).

The Hawaii section combines species new to the Peterson series with species already presented in the main species accounts section. The latter are written up in terms of their distribution, abundance, and appearance in Hawaii, with page references to the main write-up. Peregrine Falcon, for example, is annual in Hawaii in small numbers, with the Tundra subspecies most common during migration; it’s seen over coasts and wetlands and at sea in Hawaiian waters. (I did catch a minor error in the page number references for Lesser Scaup and Ring-necked Duck, which will hopefully be corrected in future printings.) Michael DiGiorgio’s illustrations, as I said above, are wonderful. I love the plate of the colorful Hawaiian finches with their parrotlike, decurved, and slightly crossed bills, but I’m really impressed by his renderings of the Kauai, Oahu and Hawaii Elepaios, each bray-brown, black, buff, and white form (male, female, juvenile, wet side, dry side) alike but different in wing and head pattern.

Conclusion

Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America, Second Edition is an updated and expanded edition of a field guide first published in 2008. It is lighter and slightly more compact than the first edition, though more birds are included. Still, it is a large book, more of a car field guide than one you can put in your pocket. A lot of work has gone into making the guide easy to use. Index and design features allow the user to identify birds, or at least to locate the materials you need to identify a bird, quickly. And, bird families are arranged in a sequence that allows for easy comparison of birds from different bird families, disregarding the continuing craziness in taxonomic order.

There is a remarkable history behind the Peterson brand, and the elements that made it a major educational force in the early days of birding still apply. I’ve said this before–we are fortunate to live in an age where we have a choice of several superlative field guides to the birds of North America. At this point, the Peterson Field Guide is the only one (I think) that also includes the birds of Hawaii. It’s an excellent field guide of choice for beginning and intermediate birders, the only question being whether to invest time and book shelf space in this edition or wait for one of the regional editions due out in the fall. It’s good to have happy choices.

I started out this review talking about the chaos of April and how a bird book, this particular bird book, made a difference. The month of May has so far been less intense, but the unknowns cast a huge shadow over our lives. I’m going to continue to rely on my books–bird books and other books–for structure and sanity, and I hope you will too.

* Julia Blakely, rare book librarian at the Smithsonian Libraries, talks about the first editions of A Field Guide to the Birds in a 2018 post of the Smithsonian blog titled “Spotting a First Edition of Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds.” This is fascinating stuff if you collect books. Laura Erickson does a great job summarizing the history of birding field guides in a 2011 post of Laura’s Birding Blog.

** Bill Thompson III wrote an appreciative account of how this first edition was created in his blog, Bill of the Birds.

*** Many thanks to editor Lisa White for answering my questions about species sequences, maps, and updating of images.

Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America, Second Edition

by Roger Tory Peterson, with contributions from Michael DiGiorgio, Paul Lehman, Peter Pyle, & Larry Rosche

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; April 2020

Flexibound; 6 x 1.2 x 9 inches; 520 pages

ISBN-13/EAN: 9781328771445; ISBN-10: 132877144X

$29.99 (discount from the usual suspects)

Leave a Comment