A bird of prey showed up in the tiny park across the boulevard from me yesterday, setting himself down on a park bench and ignoring a crowd of socially-distanced smart phone wielding photographers. He became the social media hit of the day: “A Peregrine Falcon in Forest Hills!” people proclaimed. “A Cooper’s Hawk named Sam!” my neighbor insisted. “No,” my birder friends and I chided gently, “This is a Red-tailed Hawk. See the belly band? See the white vee pattern on the back? Only a Red-tailed Hawk has these features.” I was puzzled by what seemed like a universal lack of knowledge about hawks and falcons. Where were their field guides? Didn’t every household have a copy of a Peterson Field Guide on the shelf, maybe a third or fourth edition that family members grew up with, which they could quickly consult to see the arrow pointing to that belly band? Or, a classic Golden Guide? Sadly, I did not, which is probably why I think a field guide to birds is a must in every household. And why I am so happy to see new, updated editions of Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America being published.

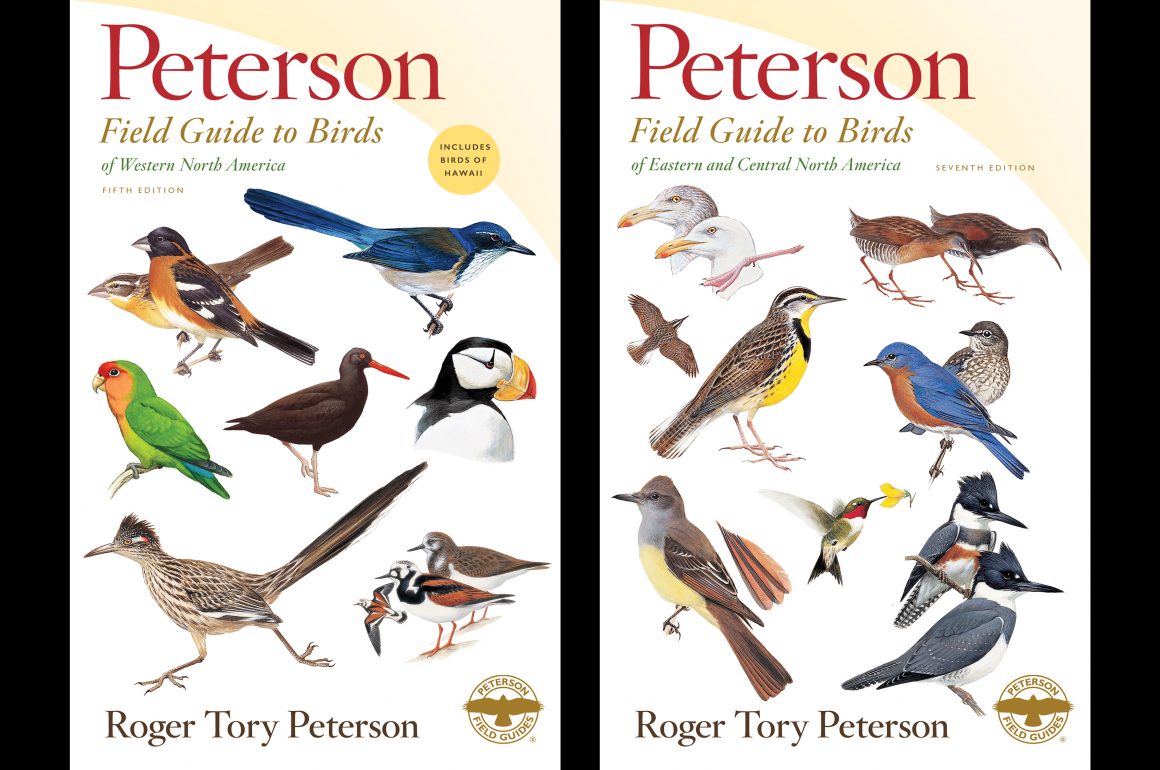

In May, I reviewed Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America, Second Edition. This month, I look at Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Western North America, Fifth Edition (available in September) and Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Eastern and Central North America, Seventh Edition (available in mid-October). Both books are by Roger Tory Peterson “with contributions” from Michael DiGeorgio, Paul Lehman, Peter Pyle, and Larry Rosche. Michael DiGeorgio painted the artwork for the Hawaiian birds and did “a few tweaks” to the existing art. Paul Lehman and Larry Rosche updated the map, with Lehman doing the data work and Rosche on graphics. (Thanks to HMH editor supreme Lisa White for this info.) I think it’s a good assumption that Peter Pyle updated and wrote species descriptions, particularly for the Hawaiian birds. The beautiful photographs, used to separate sections and on the inside cover page, are by Brian E. Small.

From “Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Western North America, Fifth Edition” © 2020 by The Marital Trust B u/w Roger Tory Peterson & © by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

UPDATES & CHANGES

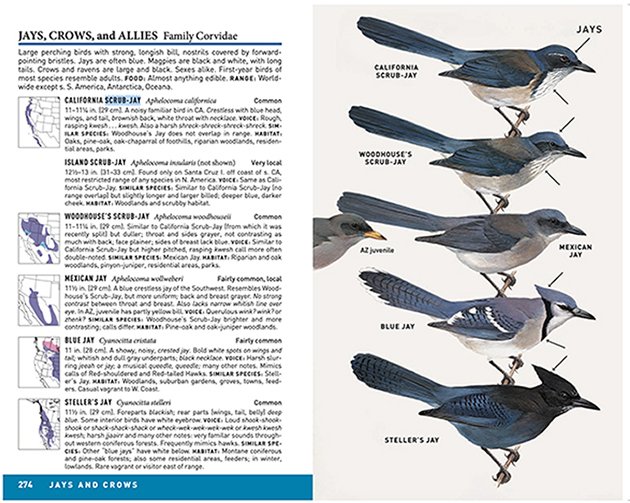

So, what’s new? It’s been ten years since the last editions of the regional editions and a lot has happened taxonomically and geographically (in listing terms). The editorial team has smartly updated text, organization, and even some of the artwork without losing the innate “Peterson” quality of the guide. There are newly determined species resulting from a decade of splits: Ridgway’s Rail, Sagebrush and Bell’s Sparrows, Woodhouse’s Scrub-Jay and California Scrub-Jay, Scripps’s Murrelet, Cassia Crossbill, and Morrelet’s Seedeater. These are the species that immediately come to my mind, and I probably missed some. any East/Central North American splits? For larophiles, there is the celebrated removal of Thayer’s Gull. The lump into Iceland Gull means it is now part of a lengthy Iceland Gull species account, illustrated in one small drawing, giving more room on the page for a larger Lesser Black-backed Gull.

There are several renamed species, including Scaly-breasted Munia (formerly Nutmeg Mannikin), Blue-throated Mountain-gem (formerly Blue-throated Hummingbird) and Canada Jay (aka Gray Jay). The book went to publication before the most recent change of McCown’s Longspur to Thick-billed Longspur, so ink that in. And, of course, there have been many, MANY changes in how species are organized taxonomically, in terms of genera, family, and order. These are reflected here, with again the exception of most recent changes, including the 2019 split of the warbler genus Oreothypis. The birds are listed in the user-friendly sequence suggested by Steve N. G. Howell in the multi-authored Birding article “The Purpose of Field Guides: Taxonomy vs. Utility?” (November 2009; thank you again, Lisa White).

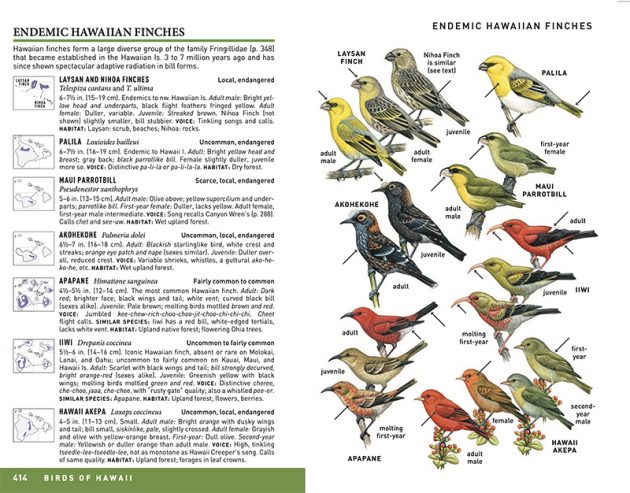

The most significant change in terms of the Peterson Field Guide series is that the Western North America guide now has a section on “Birds of Hawaii,” reflecting the inclusion of that area in the American Birding Association Checklist.** This section is also included in the Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America, Second Edition; it covers resident, migratory, endemic, introduced, and extinct birds, with briefer accounts for birds already described in the main part of the field guide. The placement of this section at the end of the guide, rather than integrating the new birds into the full text, serves two functions. It creates a mini-field guide within a field guide that can be easily used in Hawaii, and it prevents Hawaii’s endemic birds from confusing beginning birders using the main sections (and, if you’ve ever tried to explain to a new birder why a Phainopepla would not be nesting in a NYC park, then you know what I mean).

From “Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Western North America, Fifth Edition” © 2020 by The Marital Trust B u/w Roger Tory Peterson & © by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

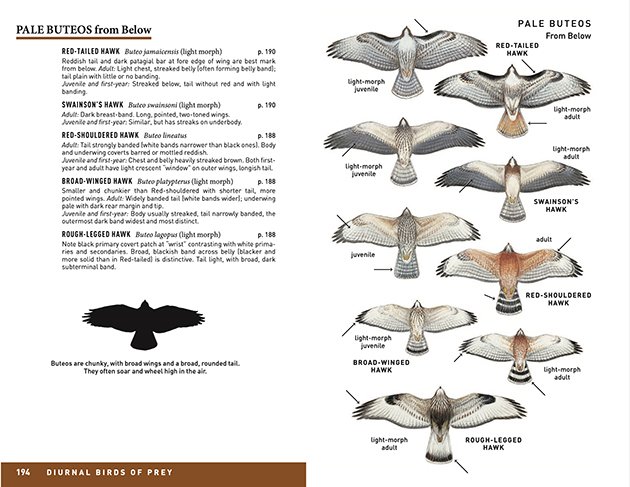

Another major change is more specificity and standardization in the terminology used for identifying age in the Species Accounts. This is described in the Introduction under “Identifying the Age and Sex of Birds”: terms such as “immature” have been replaced with age groupings such as juvenile, adult, first-winter, first-summer, etc. and plumage terms such as “breeding” and “nonbreeding” have been replaced with “spring/summer” and “fall/winter.” The change jumps out at you in the Gulls, Terns, Hawks, and Shorebirds sections, where identification of different plumages can be particularly challenging. The contributing authors have “made an effort to point out every identification age and sex classification of each species, illustrating many of them” (p. 13, Eastern/Central ed.).

It seems like every species account has been reviewed and tweaked–changes in phrasing, some words taken out, some words added, a tightening of focus, a nonstop effort to make clear which ages and sexes have which plumages and how the bird differs from similar species. It’s interesting, at least to me, to make comparisons. Red-tailed Hawk in 2010 was “The common hawk of roadsides and woodland edges;” in 2020, it’s “The common conspicuous hawk of roadsides and woodland edges.” In 2010, Yellow Warbler is introduced with one of Peterson’s classic phrases, “No other warbler is so extensively yellow;” in 2020, the bird is simply “Extensively yellow, with yellow tail spots and yellow edgings to wing and tail.” In 2010, Surf Scoter is introduced as the “skunkhead-duck”; in 2020, it is “Medium-sized, the most common scoter along Atlantic Coast.” (Note: all these quotes are from the Eastern/Central guides.)

There is definitely a trend here, so I decided to look further back, at the first Peterson bird guide I owned, A Field Guide to the Birds: A Completely New Guide to All the Birds of Eastern and Central North America, fourth edition (1980). Here I found species accounts that were much shorter, less detailed, but more memorable. Red-tailed Hawk is introduced with the words of an artist: “When this large, broad-winged, round-tailed hawk veers in its soaring, the rufous of the upperside of the tail can be seen (if adult).” Piping Plover is “As pallid as a beach flea or sand crab, the color of dry sand,” while in 2020, it is “Quite pallid in color, like dry sand.” Reddish Egret “lurches about, acts drunk” when feeding,” while in 2020 it “races about with spread wings.”

There are other changes from Peterson’s original prose, and I’m sure there are good reasons for this–the need to utilize page space more efficiently; a general trend in field guides towards specifying more than one or two diagnostic field marks; the growing wealth of knowledge in bird identification; the growing sophistication of birders and bird watchers. At the same time, I hope these demands don’t totally eliminate Peterson’s words, which for some of us are as distinctive as his illustrations.* I am relieved to see that Eastern Whip-Poor-Will still “flits away on rounded wings, like a large brown moth.” And, that Winter Wren is still “mouselike, staying close to ground,” and that Barn Swallow is still “our only swallow that is truly swallow-tailed” (you have to love Peterson’s way of zeroing in on a species’ one special trait). And, there are also–dare I say it–some improvements. Sandwich Tern’s “long black bill with its yellow tip” is now a “long black bill with yellow tip ‘as though dipped in mustard'” (frankly, I was shocked that mustard wasn’t there all along). And, though the capture of a Chimney Swift’s flight as “batlike” has been removed, editors have kept the twinkle and the bow of Peterson’s rather long description: “Rapid, twinkling wingbeats interspersed with bowed-winged glides.” I hope they continue to honor Peterson’s prose in future editions.

Additional changes in format from the 2010 edition includes less maps, a little more Introduction, the One-Page Index handily in front AND in back. Also, sadly, the elimination of the Preface by Lee Allen Peterson (Roger Tory Peterson’s son) and an Editor’s Note by Lisa A. White. Please put these back, HMH. The Preface gave the Peterson Guide’s history and explained how the first guide revolutionized field identification and birding; the Editor’s Note talked about how the contribution team revised and updated Peterson’s work. Both of these very brief essays gave essential context to old and new readers (and reviewers).

The separate Maps section has been eliminated. This is too bad. Though most species accounts have a range map, they are very small. The larger maps in the back were easier to see, could be compared to maps in earlier editions to see distribution changes, and gave additional information on migration routes. Some of the latter has been added to the 2020 species account maps by the addition of yellow to denote traditional migration range. On the positive side, less pages means that the Eastern/Central Guide is more portable and that the Western Guide, with its additional Hawaiian section, is not too thick.

From “Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Western North America, Fifth Edition” © 2020 by The Marital Trust B u/w Roger Tory Peterson & © by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

THE BASICS

Here are the basics of the Peterson Field Guide to Birds 2020 regional editions. The Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Eastern and Central North America, Seventh Edition covers resident and migratory birds from the Atlantic coast west to a line that runs roughly along the 100th meridian (western border of Nunavit and Manitoba, down through the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, most of Oklahoma, and the eastern part of Texas). Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Western North America, Fifth Edition covers resident and migratory birds west of that line, including the Hawaiian islands. (The guides do not cover the area south of the United State border, a limitation common with “North American” field guides.) The field guides also cover introduced, vagrant, accidental, and even notable extinct birds within their areas.

Peterson Field Guides are known for three things: illustrations, arrows, and silhouettes. In the Preface to the first edition of the field guide, Peterson wrote that he was aiming for a “‘boiling down,’ or simplification of things …. so that any bird could be readily and surely told from all the others at a glance or at a distance.”*** His birds are drawn and painted simply yet specifically, clean lines and patterned colors. Lee Allen Peterson wrote in the 2010 Preface, “Someone once confided to me that Dad’s rendition of a robin was not only a robin, but the perfect robin. Somehow he was able to convey a bird outside of a specific moment in time and place: the robin idealized, with feathers neat patterned and plump” (pp.. ix-x).

These images are organized on the left page of the species accounts, (or “Plates,” as the section is titled), swimming, flying, or perched on branches, usually but not always drawn in profile facing or flying in the same direction, mostly full figure but sometimes with heads, feet, tails, even chicks included to illustrate sex and age differences or differences amongst similar species. Although white is the predominant background color, shades of green, gray/green and gray/brown are effectively used for certain families–geese and swans, ducks in flight, jaegers, gulls, chickadees, titmice, vireos are some examples–beautifully bringing out the birds’ colors (especially the white and black and yellow-billed gulls) and giving the eye relief from the white.

But, it is chiefly the arrows that focus the eye on important identification features, usually one arrow per image, but sometimes as many as three. The arrows work best when you’re studying a page of similar species; looking at the page of Kingbird images in the Eastern/Central guide, for example, one notes the pale gray breast of Western Kingbird, the white tipped tail of Eastern Kingbird, the large bill of Gray Kingbird, the shorter and smaller bill of Couch’s Kingbird (head only), and the bright yellow underparts of Tropical Kingbird.

Text for the species accounts are on the right-hand page. Information is brief and concise with a focus on identification features in plumage, bill shape, voice, and sometimes behavior and habitat: common and scientific names of the species; references to other depictions of the species in the guide; abundance status for the region (common, common off-shore, scarce-local, etc.); measurements; a description of the species and plumage differences for sex and age, with diagnostic field marks set off in italics; description of voice, often with transcriptions of sound; similar species and how they are differentiated; habitat, and a small range map. Notable subspecies are also noted; for example, almost a whole page is devoted to the Dark-eyed Junco five subspecies groups.

And, then there are the pages that are different, that seem to be placed in the book just for you because Peterson knew you would have trouble identifying hawks in flight, sandpipers and waders in flight, first-fall Empidonax flycatchers, fall warblers (they are “fall warblers” now, no more “confusing fall warblers”). My particular favorites are the species account pages for Empidonax flycatchers; the illustrations depart from the usual groupings to present the look-alike flycatchers in a four-part checkerboard with a fifth image in a central circle and a couple of identification tips in a smaller circle.

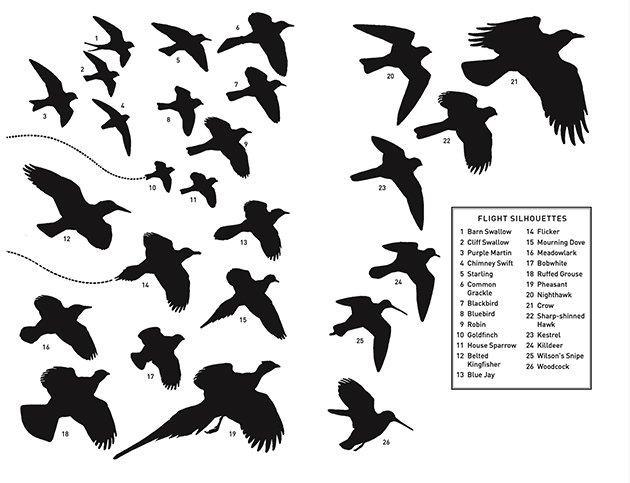

Back to the silhouettes. Originally presented as endpapers in the first field guide editions, the iconic Roadside Silhouettes and Flight Silhouettes are now in the back of the book with the addition of Shore Silhouettes (which was also in the 2010 editions). More silhouettes show up in the 2-page introductions to Shorebirds and Birds of Prey in the species accounts, plus some additional outlines scattered throughout these sections. They are a reminder that though Peterson is chiefly remembered as the guy who singled out (with arrows) one or two diagnostic field marks for each species, he also knew the value of size and shape. These iconic pages are still useful study aids. And, you can see their influence in more “modern” guides, such as The Shorebird Guide.

Flight Silhouettes from “Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Western North America, Fifth Edition” © 2020 by The Marital Trust B u/w Roger Tory Peterson & © by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

In addition to species accounts, the field guides offer the standard Topography of a Bird (it’s in the front of the book, opposite the title page), an 18-page Life List Index (the ABA Checklist as of 2018) in the back, and an Introduction. This is oriented towards beginner birders, giving basic instruction in how to identify a bird; some basic information about bird nests, habitat, and subspecies; conservation resources; a little background on range maps and how to use the ones in the guides; and, as I said above, an explanation of the terminology used to identify the age and sex of birds. I really would have liked more detailed information about how to use the species accounts and how the updates were written and edited.

The guides employ a variety of devices to help users locate bird families and species: a table of Contents; a One-Page Index of major species and families, placed in the front and the back for quick convenience; a more detailed index which lists species and families by both common and scientific name; color-coded bars at the bottom of the page to denote different sections, and a full-page Legend to Range Maps, also placed at the front and the back of the book. Graphic design is smartly employed as well. Large type headings and color bars set off each family section, followed by a brief summary of common characteristics, food, and range of the species that comprise the family. Birds on the illustration pages are clearly labelled in bold capital letters with age and sex labelled in small cap letters. The font of the text itself is highly readable, larger and darker than fonts in other prominent field guides. In portability terms, the books are lighter than their 2010 versions, particularly the Eastern/Central guide, though still a too large for a pocket. Definitely, a field guide that belongs in your backpack or car.

In conclusion, Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Eastern and Central North America, Seventh Edition and Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Western North America, Fifth Edition are thoroughly updated editions of classic identification titles which continue to refine and expand the Peterson tradition of schematic identification and ornithological education. If this is your field guide of choice, you will want to purchase the updated guide for your region. So much has happened, so many splits and renamings! And, with the Western North American guide, you get Hawaii! These guides are also highly recommended for beginner birders (it was my first field guide, and the one I always use when helping on a field trip), birders traveling to Hawaii (when we can travel to Hawaii), birder who want an updated field guide to supplement the other titles on their shelves, and as a gift for those families just beginning to watch and identify birds as a result of virus restrictions (and, there are many). Know your neighborhood hawk!

—————-

*Ted Floyd wrote a great ABA Blog post on the iconic aspects of Peterson’s words.

** Book review colleague Ian Paulsen reminds me that earlier editions of the Western field guide also included Hawaii. The islands were part of both first and second editions, formally titled A Field Guide to Western Birds: Field marks of all Species found in North America West of the 100th Meridian, with a Section on the Birds of the Hawaiian Islands (1941 & 1961). Thanks, Ian! Thanks, Wikipedia!

*** Quoted in “Knowing a Hawk From a Handsaw” by Laura Jacobs, Wall St. Journal, May 25, 2012. Unfortunately, I don’t have a first edition of Peterson’s first, 1934 field guide, titled A Field Guide to the Birds, giving field marks of all species found in eastern North America, though I did find one selling for $17,500.

Many thanks to HMH for providing review copies.

Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Western North America, Fifth Edition (Peterson Field Guides)

by Roger Tory Peterson, with contributions from Michael DiGeorgio, Paul Lehman, Peter Pyle, and Larry Rosche.

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, September 2020. Vinyl Bound, 5 x 1.03 x 8 in., 480 pages.

ISBN-10 : 132876222X; ISBN-13 : 978-1328762221. $19.99. (slight discount from usual suspects)

Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Eastern & Central North America, Seventh Edition (Peterson Field Guides)

by Roger Tory Peterson, with contributions from Michael DiGeorgio, Paul Lehman, Peter Pyle, and Larry Rosche.

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, October 2020. Vinyl bound, 5 x 0.84 x 8 in., 392 pages.

ISBN-10 : 1328771431; ISBN-13 : 978-1328771438. $19.99. (slight discount from usual suspects)

Thanks Donna, great review as always. I guess it isn’t too early to put some new field guides on my holiday wish list!

Thank you so much for this thorough and helpful review!