Of all the living things in our world to be passionate about, mushrooms may rate as the most unlikely. Ranging in color from off-white to dingy black, with pastel to gelatinous shades of yellow, orange, purple, and brown in-between, found in moist crevasses, decaying trees, rain-soaked pastures, mushrooms lack the beauty of butterflies and wildflowers cannot equal the action of bats, or flying fish, and certainly lack the spiritual zest of birds. Yet, they are fascinating. You can eat mushrooms! They may enliven your omelet, boost your immune system, or induce hallucinatory dreams. There is a cultural connection between mushrooms and folklore, even literature and art. Fairy rings, a circle of mushrooms in a forest, are where witches (or fairies, depending on your choice of lore) dance on Walpurgis Night. Lewis Carroll’s “hookah smoking caterpillar” pontificates from atop a mushroom (one side makes you larger, one side makes you small). There is a mushroom hunting expedition in Anna Karenina, Tolstoy’s use of a popular Russian pastime. Cy Twombly created a series of collages centered on cutouts and drawings of mushrooms, considered one of his most important works of the 1970’s. So, when I was offered the opportunity to review a new identification guide on mushrooms, I was happy to do it.

Peterson Field Guide to Mushrooms of North America, Second Edition by Karl B. McKnight, Joseph R. Rohrer, Kirsten McKnight Ward, and Kent H. McKnight is not totally new, it’s a revision of A Field Guide to Mushrooms: North America (Peterson Field Guides) by Kent H. McKnight and Vera B. McKnight published in 1987. The guide has been expertly, even lovingly revised, expanded and updated (as the authors’ names indicate, this is largely a family affair). I will be reviewing the guide as a novice in the field of mushroom identification, asking if this is a guide that a beginner could use. Hopefully, my description of the guide and its unique organization will also be useful to more advanced mycological enthusiasts. Comments, especially from mycologists, are welcome.

copyright © 2021 Karl B. McKnight, Joseph R. Rohrer, Kirsen McKnight War, and Kent and Vera McKnight

This second edition covers 685 species found in the continental U.S. and Canada, including some species as far north as Alaska, an increase over the 500 species covered in the first edition. The authors note in the Introduction that this number is far from comprehensive, but it is representative of the “most common and important” mushrooms of the continent (p. 29). To get an idea of how many mushroom species are around us, in 2018, the journal Mycologia published a checklist of North American fungi. 44,488 fungi species were listed, of which about 20,000 are mushrooms, and the authors estimate that the list represents only about one-third of the fungi existing in North America.* Which makes me really appreciate our birding checklists.

Additional changes include expanded geographic coverage; updating of species descriptions; illustrations by other artists and hundreds of drawings by original artist Vera B. McKnight not included in the first edition; updated nomenclature; and artwork positioned opposite the species descriptions. The updated nomenclature is a very important feature. As in the ornithological world, there has been a major shift in groupings and scientific names of mushrooms. Originally organized by structure and ecology, they have been reclassified according to relationships discovered by DNA research. Lots of splits too, with many species formerly considered identical to European species now considered separate species. (Hey, it’s not just us!)

copyright © 2021 Karl B. McKnight, Joseph R. Rohrer, Kirsen McKnight War, and Kent and Vera McKnight

Species Accounts

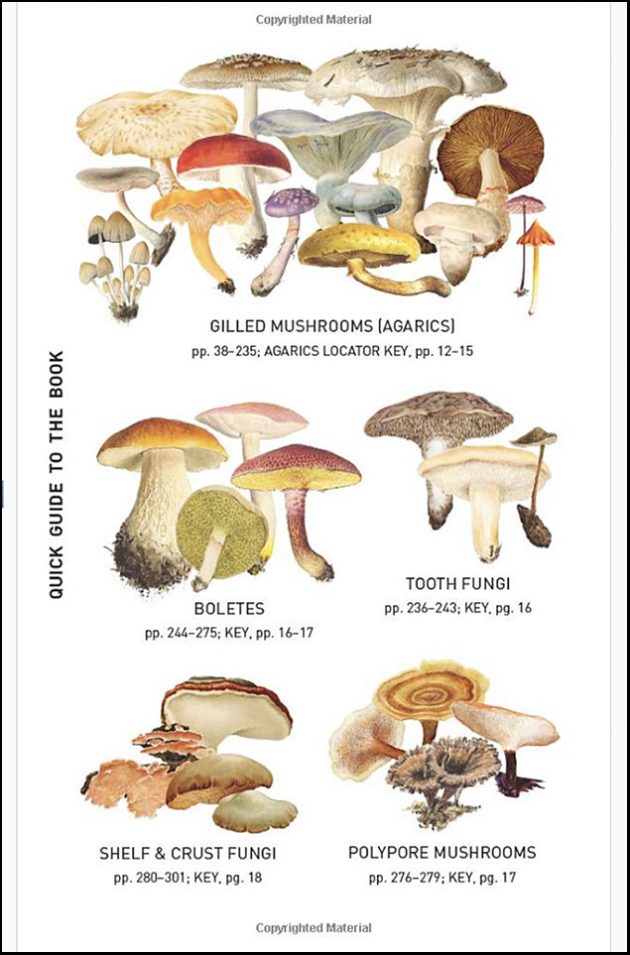

The Species Accounts are organized into 12 sections, coded by colored tabs placed on the bottom of the left page and along the edge of the right page: (1) Fleshy Gilled Mushrooms (Agarics); (2) Tooth Fungi; (3) Boletes; (4) Polypore Mushrooms; (5) Shelf and Crust Fungi; (6) Coral and Club Fungi; (7) Jelly and Miscellaneous Fungi; (8) Cup Fungi; (9) Morels, False Morels, and Saddles; (10) Stinkhorns; (11) Puffballs, Earthballs, and Earthstars; and (12) Bird’s Nest Fungi. The authors define a mushroom as “the macroscopic fruiting body of a species belonging to the kingdom Fungi” and note that although the most familiar mushroom species have stalks and caps, “we include the whole array of fruiting bodies seen at the front of the book (boletes, polypores, corals, cups, puffballs, stinkhorns, etc.)” (p. 22). The locator key section in the front of the book summarizes the shared characteristics of each mushroom type. In many cases these are obvious–Jelly Fungi have a gelatinous texture–and in other cases it’s really not–Boletes, for example, look superficially like Agarics with their cap and stalk structure, but don’t have gills, the lower surface is covered with pores that are the ends of tubes. (The Boletes and Polypores share the same color coding and placement, and I’m not sure why. Like Boletes, they have tubes, but they are separate groups according to my reading.)

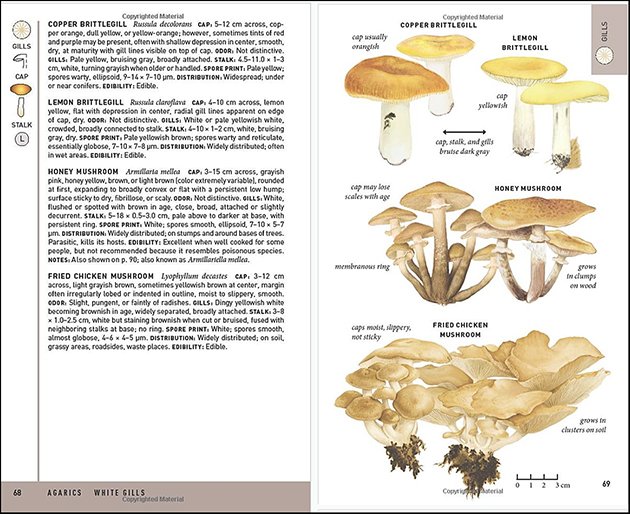

There are three to five species described on each page, text on the left, illustrations on the right. Each account includes: common and scientific names; size of cap or cup or length of fruiting body; description of shape and color, including range of colors and changes in shape, size and color as the mushroom ages; odor; description of ‘spore print’ (a method of mushroom identification); distribution; edibility; notes on alternative or old names. Physical descriptions vary according to type of species: details on gill and stalk color and size, whether the surface is porous or hairy, the changing colors of the spore mass at the center of a puffball. The text is very readable here and throughout the book, with bolded, italicized, and capitalized terms helping the eye find the required information.

I was fascinated to see that the question whether a mushroom can be eaten safely is not a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no.’ A mushroom’s edibility might be unknown, unknown but surely not worth the effort, unknown but could be confused easily with close relatives that are poisonous, not poisonous, edible and good, widely eaten and highly prized but cook thoroughly, edible, edible but poor, unpalatable, not edible, inedible, mildly poisonous, poisonous. The edibility of most species is unknown. I imagine part of the allure of studying mushrooms is the tension between identifying the ones that will kill you (or at the very least give you a tummy ache) and the ones that will make your pizza or salad zing. I prefer buying my omelet mushrooms in the local vegetable store, but there are a lot of people who want to identify mushrooms so they can eat them. The publishers start the field guide with a strongly worded warning, the authors are a bit more lenient but warn to only eat mushrooms collected and identified with a professional. They expand on what toxins mushrooms may contain and how their effects will differ depending on your own body and allergies in the Introduction. For example, I had no idea that some mushroom poisons only work when ingested with alcohol–watch out when you eat those morels!

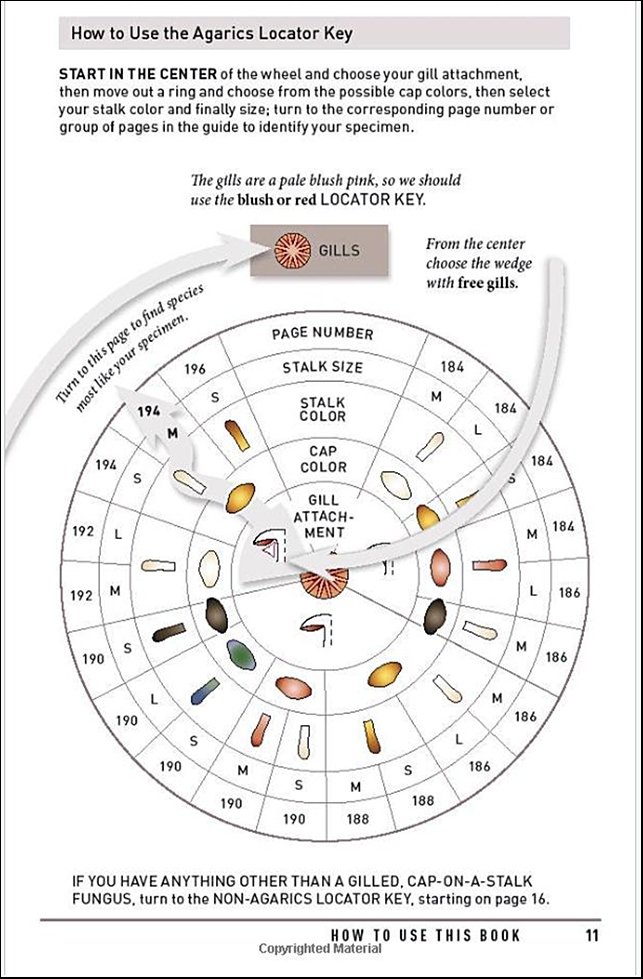

The Fleshy Gilled Mushrooms (Agarics) section, 230 pages long, takes up over half the book. It’s divided into six sub-sections coded by gill color: white or buff; yellow or orange; caramel or rust; blush or red; purple, blue or green; dark brown black, or gray. Gill color is written out on the bottom gray-colored tab and shown graphically on the gray side tab (see above image). It’s a key element to the book’s identification system, as are the ways in which the gills attach to the cap, cap color, stalk color, and stalk size. Icons denoting the specifics of each feature are part of the text descriptions, easily seen in the left-hand margin.

Illustrations

A lot of work has clearly gone into the artwork. Vera Lena McKnight created the original drawings, mostly black-and-white, some watercolors, for the first edition. (Ms. McKnight’s full name was Vera Lena Babbel McKnight. She was credited as Vera B. McKnight in the first edition and as Vera Lena McKnight in the edition. Ms. McKnight passed away in 1998. I was unable to find out anything more about this very talented illustrator.) To these were added images by Louis C. C. Krieger, Joseph Bridgham, Jakob E. Lange, late-19th/early-20th century botanical illustrators and mycologists (Krieger was “considered the finest painter of North American fungi,” according to Wikipedia) plus drawings by modern-day medical and botanical illustrators Joan Thomson, Lara Gastinger, and Angela Mele. The older illustrations have been digitally adjusted and in some cases colorized by Kirsten McKnight Ward (Vera’s granddaughter), who also designed the book as a whole.

The illustrations do a wonderful job showing us the diverse hues, shapes, textures and sizes of mushrooms, from the reddish caps of young Goldgills to the algal green shelves of Mossy Mazegill to the dark blues inside flute-shaped Blue Chanterelles to the densely branched Crested Coral (which really does look like coral) to the poofy, spherical Earthstars. There is great beauty in mushrooms, and the drawings are worth looking at just to enjoy the subtle colors and organic lines. But the goal is identification and the original artists and Kirsten McKnight Ward have taken care to show significant features–droplets on gills, bulbous ends of stalks, underside colors and textures. Each species is boldly labelled on the page and significant identification points are noted in italic text, sometimes punctuated with a Peterson arrow. Also, a scale bar at the bottom of the page indicates the scale to which the mushrooms are drawn; there are notes where species significantly smaller or larger than the scale.

Identification Keys

So, here is how the Agarics identification system works–select a Locator Key in the front of the book that corresponds with the gill color (the one below is for blush or red). Starting from the center, go through each ring–they correspond to the other key features–till you land on a page number (or several pages). This page (or pages) will display the species most like the mushroom in hand, and you now need to read the descriptions, study the drawings, and identify. Interestingly, because some mushroom species may have two or more gill colors at different stages, some of the mushroom species accounts are repeated throughout the book. I’ve never seen that in a field guide before.

copyright © 2021 Karl B. McKnight, Joseph R. Rohrer, Kirsen McKnight War, and Kent and Vera McKnight

The Agarics Locator system is unique to this guide. (I don’t think it was a part of the first edition I don’t have a copy, but much of the Introduction is available through Amazon’s ‘look inside’ feature). Looking through mushroom websites, descriptions of identification guides, and the one already in my library, mushroom identification appears to be a system in process, or maybe a series of systems, some of which work for beginners, others–involving microscopes–that are more appropriate for professionals. The beginner and intermediate systems all involve spore prints (the Peterson Guide gives instructions on how to make them and there are of course tutorials by enthusiasts on the Internet) or flow charts or keys, some of which require reading long lists of choices on cap color, gill attachment, pore texture, stalk length, and whether the mushroom was fruiting on dung or grass. The Peterson system, though not totally precise (and the authors give suggestions for working it when there are no results), appears to be a relatively easy way to begin learning identification. The keys look intimidating, but they’re really not once you’ve studied what each feature is.

There are also locator keys for the non-agaric (non-gill) mushrooms. These are much simpler, depending on the features on the specific group. To identify Boletes, for example, you need to look at the color of the pore surface on the cap underside and the texture of the stalk. For Bird’s Nest Fungi, you simply examine the four species accounts. Identification of all mushroom species entails proper collection, detailed in the Introduction. The Introduction also reviews what a mushroom is, the basics of mushroom identification, mushroom naming issues, geographic distribution, additional resources, the importance of mushrooms to our ecology, and edibility. It’s well written in plain language and presents an encouraging framework for studying a life form that is fragile, short-lived, and often chameleon-like in color and texture.

Useful Features

Like all good field guides, Peterson Field Guide to Mushrooms of North America, Second Edition offers numerous features for locating information and learning background, contextual knowledge. A Quick Guide To The Book is found on the inside front cover, a handy tool for going directly to the type of mushroom you’re researching (see top illustration). The visual guide combines different species for the illustration of each chapter and gives page numbers for Species Accounts and Keys. The back inside cover offers answers to Frequently Asked Questions and has a ruler (in centimeters) along the side. There are two indexes: an Epithet Index, very useful if you know the genus of the mushroom in question (‘epithet’ is used here in the taxonomical sense, it’s not a nickname index like I originally thought); and an Index of scientific and common names (remember that many of the common names here were assigned by the authors).

Additional back-of-the-book material includes an Illustrated Glossary, Acknowledgements, and Illustrator Credits. The glossary is a bit disappointing. Only two pages long, it illustrates specific processes and physical features of mushrooms–“universal veil’ and ‘partial veil,’ for example. I looked at the glossary several times while I was doing this review but could not find terms that mushroom enthusiasts know but beginners may not, such a ‘agaric’ and ‘gill’ (though there is a useful diagram of the anatomy of an agaric). The illustrator credits section gives a little background on how the artwork from the first edition was digitally adjusted and colorized; I always find this type of ‘how the book was made’ information fascinating. It also gives page and figure credits for the illustrations of the additional artists.

Conclusion

Peterson Field Guide to Mushrooms of North America, Second Edition is an intelligently constructed, beautifully illustrated field guide of a life form many birders and naturalists find intriguing. Mushrooms are an essential part of our ecology. They have symbiotic relationships with plants and trees and assist with the decomposition of dead plants and animals. And we’re still discovering new things about them. For example, recent studies have determined is closer to animals than plants.

The Field Guide is an excellent starting point for learning more about mushroom species and how to identify them. It’s also the most up-to-date field guide on North American mushrooms by more than 10 years and one of the few guides illustrated with drawings. (North American Mushrooms: A Field Guide To Edible And Inedible Fungi by Orson Miller and Hope Miller was published in 2006 and the popular Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mushrooms by Gary Lincoff came out in 1981. Both these guides are illustrated with photographs.) I’m looking forward to using the guide in the near future, assuming the snow melts and we can venture into the woods, fields, gullies, and marshes. Mushrooms! They’re more than a pizza topping!

* “North American checklist identifies the fungus among us,” by Diana Yates, Univ. of Illinois News Bureau, Nov. 28, 2018, https://news.illinois.edu/view/6367/722471.

Peterson Field Guide to Mushrooms of North America, Second Edition

By Karl B. McKnight, Joseph R. Rohrer, Kirsten McKnight Ward, Kent H. McKnight

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, January 2021.

Paperback, 416 pages, $23.99 (discounts from the usual suspects)

ISBN-13: 978-0544236110; ISBN-10: 0544236114

Leave a Comment