Once upon a time, bird field guides included nests. This may have been partly a leftover from the Victorian fascination with egg collecting (the infamous passion known as oology), but probably more from people’s burgeoning interest in the nests and eggs found in their gardens and fields, gateway artifacts to a newer hobby called birdwatching. Florence Merriam Bailey wrote about nests with both passion and scientific precision in Birds Through an Opera Glass, published in 1889 (she spends three pages on the difficulties of finding a Bobolink nest and then instructing the reader on how to do it, really a lesson in field ornithology) and later gave just the facts on species’ nests and eggs in her Handbook of birds of the Western United States, published in 1902. Decades later, Richard Pough’s Audubon Bird Guide, Eastern Land Birds (I happily own the 1948 edition) included nest and egg descriptions for each species as well.

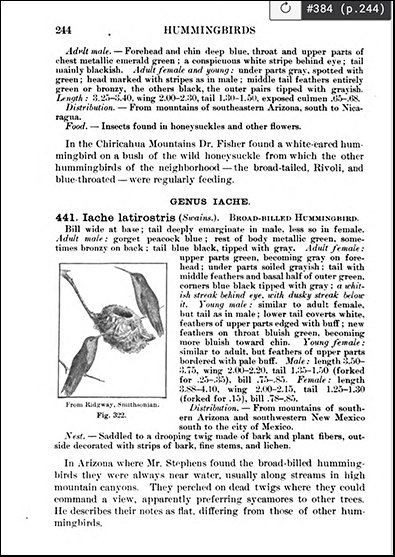

Description and drawing (from Ridgway) of a Broad-billed Hummingbird nest from Handbook of birds of the western United States, including the great plains, great basin, Pacific slope, and lower Rio Grande Valley by Florence Merriam Bailey, 1902. Text retrieved from the Hathitrust Digital Library.

But somewhere along the way, nests and eggs got dropped from our field guides. Species accounts–bird descriptions–were condensed and streamlined in the name of identification and most of us didn’t even miss nest descriptions till we started participating in nesting bird surveys. Or, maybe, wanted to answer our non-birder relatives’ questions about bird behavior as they took pandemic walks and looked at nature for the first time in 20 years; or maybe wanted to branch out from photographing birds at water holes and illustrate some of the more hidden parts of bird parenting, without disturbing the birds themselves. There are many reasons to inquire about bird nests (and eggs) and how to identify them.

The Peterson Field Guide series published separate guides to bird nests in the 1970’s, one for Eastern birds’ nests and one for Western birds’ nests, both authored by Hal H. Harrison. (A bit ironic since it was probably Peterson’s emphasis on pure identification points that spurred our lack of nest information in bird field guides.) The Harrison guides are out of print. A classic guide, Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds, was written by Paul J. Baicich and Colin J. O. Harrison in 1978 (it is now in its second edition, 2015, PUP). This excellent book describes nests but has few images of them, the color plates are of the nestlings and eggs. So, as a participant in the NYS Third Breeding Bird Atlas project, I am very happy that we now have this updated, user-friendly guide, the Peterson Guide to North American Bird Nests by Casey McFarland, Matthew Monjello, David Moskowitz, presenting bird nests and bird behavior when it comes to their nests in classic organized, fact-filled, pictorial Peterson style.

Scope

The authors’ goals are (1) to provide information that will help readers identify a bird nest; (2) to explore the broader ecology of bird nests of North America, “an ecological study of how hundreds of species have adapted nests and nesting behavior to environs that range from tropical deciduous forest to Arctic tundra” (p. 3). The first is accomplished well. The second is more of a challenge given the constraints of the field guide format and the scope of the book, but the introductory chapters and a close reading of the species accounts do give a sense of the complexity of nests and how they are built and used. The guide covers over 650 species, most of the breeding birds in the United States (minus Hawaii) and Canada (like most guides with ‘North America’ in its title, it does not include Mexico or the Caribbean). It is a photographic guide, offering over 750 photos of nests–empty nests, nests being built, nests with eggs, eggs with parents brooding eggs. There are also drawings of nests and eggs in the introductory chapters. And photographs of feathers in the species accounts, which surprised me. It turns out that duck nests tend to be so similar that you need to identify the feathers lining the nest, usually the breast feathers of the parent, to identify the user. Who knew?

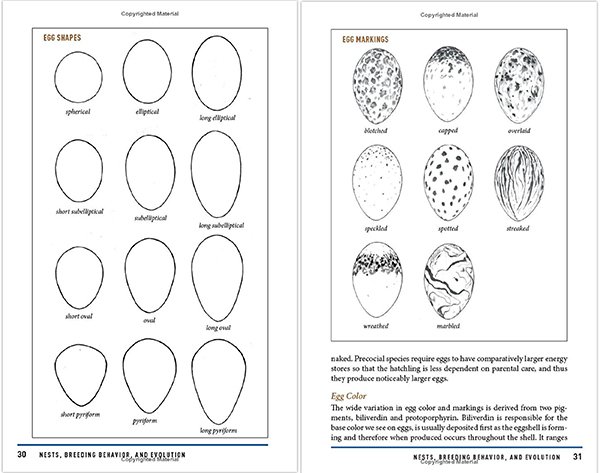

pages 30 and 31, Chapter 1: Nests, Breeding Behavior, and Evolution; copyright 2021 by Casey McFarland, Matthew Monjello, David Moskowitz

Introductory Material

There is a lot of introductory material. The “Guide to Using This Book” is worth reading for all the usual reasons and for general principals of bird nest identification. There is also a Nest Key, a four-page listing of nest categories–nests organized by shape, material, habitat–and the birds who build those nests. Have you seen a nest with its Outer Layer Decorated with Lichen Flakes? Possibilities are hummingbirds, Least Flycatcher, gnatcatchers Cerulean Warbler, and Olive Warbler. Small to Medium Passerine Cup Nests in Shrubs, Trees, and Tangles, Built with Coarser Materials; Mud or Leaf Mold Possible? Many possibilities, including most thrushes, waxwings, some towhees, some finches, some warblers, some icterids; some tanagers; Northern Cardinal. No Nest, in Divot in Moss on Branch of Mature Conifer in Old-Growth Forest? Only one possibility, Marbled Murrelet. (I should be so lucky.) The idea is to give you a start in the identification process, and of course knowing which species are possible in your area helps narrow the possibilities down further.

The chapters on “Nests, Breeding Behavior, and Evolution,” and “Avian Architecture: Nest Design, Materials, and Construction” are excellent introductions to the history, ecology, diversity and wonder of nests. Even if you are familiar with this material, the textbook-like definitions of terms used to describe mating systems, the illustrations and naming of egg shapes and patterning (see above illustrations), the drawings of nest placements, and the descriptive listings of nest materials, building techniques, and types are good reminders of the vocabulary and context necessary to identify nests and learn about nesting behavior.

Species Accounts

Species are organized by family and families are arranged in taxonomic order according to American Ornithological Society’s Checklist of North American Birds, 7th edition through the 59th Supplement (2018). Each family section begins with a Group Account, an overall section giving the number of species in the family and nesting commonalities and differences. These paragraphs provide essential information about habitat, behavior and nest structure, and also information that may not be repeated in the individual species accounts. The organization varies, and there are sometimes more than one Group Accounts for a family. “Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae),” for example, has a Group Account for Gulls and another one for Terns and Skimmers. Sometimes there’s even more than text! Plop in the middle of the sparrow section I found the Sparrow Nest Quick-Look Chart, a 2-page spread listing sparrow species and columns for nest placement, habitat, and unmarked eggs (an identification characteristic). So, browse through the whole section of the bird family you’re researching to make sure you haven’t missed anything. (To be fair, the Sparrow Chart is cited in the sparrow family group write-up, but it could be easily missed.)

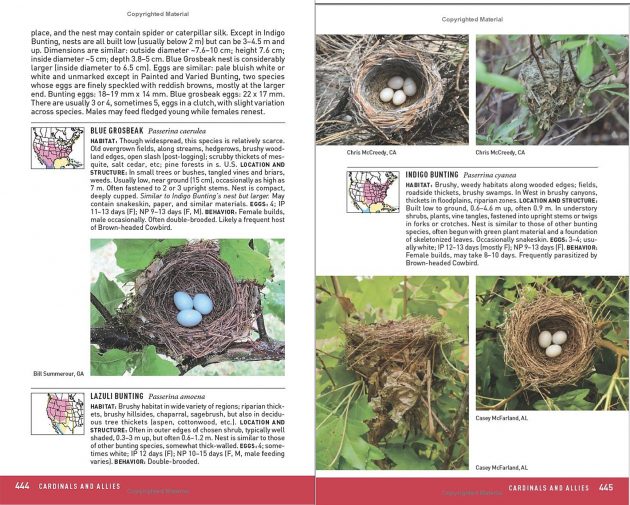

pages 444 and 445, Species Accounts, copyright 2021 by Casey McFarland, Matthew Monjello, David Moskowitz

An individual Species Account gives the following information: common and scientific name of the bird; a small range map showing summer, winter, and year-round ranges; and information on Habitat; Location and Structure [of nests]; Eggs (likely number, incubation period, nestling period, often color and shape); and Behavior. The sections are concise, detailed and sometimes surprisingly long. Some species have developed diverse ways to successfully nest. Grasshopper Sparrows, for example, usually nest in “relatively dry, open grasslands and prairies of intermediate height with patches of bare ground and sparsely scattered shrubs,” but also nest in cultivated fields and, in Florida, in palmetto prairie; they utilize less vegetated sites in the Midwest and East and shrubbier sites in the Southwest and West, and “generally avoids grasslands that are densely vegetated with shrubs” (p. 377). The nest of the Yellow-throated Warbler may be in “a clump of Spanish moss where occurring…far out on a horizontal branch” or “in a cluster of pine needles or leaves near end of branches, saddled to branch in open, or neatly wedged or fastened in upright forks” (p. 433). The nest can be made of weed stems and bark strips, leaf fragments, moss and lined with grass, weeds, moss, or feathers. Acorn Woodpeckers use both communal and cooperative breeding strategies which vary widely among family groups. Harris Hawks are monogamous and polyandrous and the female is the primary nest builder. The male House Wren builds dummy nests, attracting a mate who then selects her nest and completes construction.

There are species accounts, however, that I thought deserved expanded text. Burrowing Owl nests are described as “usually in a mammal burrow (but on rare occasions dug by owls if soils permit and other burrows are lacking), often in concentration of multiple burrows” (p. 226). The account omits the important information that Burrowing Owls in Florida, and probably those in the Caribbean, “usually excavate their own burrows” (Birds of the World*). I understand that the species accounts needed to be abbreviated, and the authors talk about this in the introduction. But many birders see their life Burrowing Owls in Florida, and not knowing that self-made burrows are the norm there could lead to a basic misunderstanding about their lives there.

There is some variety in the organization of species accounts, and not all species get the full treatment; instead, descriptions are combined in the group account or a previous species account or several species are presented together. This happens a lot in the shorebird sections. It sounds more complicated than it is in practice; the information is all there, you just need to read the whole group section. I assume the reason behind this organization is to reduce redundancy and save page real estate. It can make the book a little difficult to use till you get used to it. As constant users of bird field guides, we are very used to a more same-on-every-page, cookie cutter organization.

Many species accounts are illustrated with one or more photographs showing what the species’ nest looks like in the field. But not all and the omissions are sometimes puzzling. Is there no photograph of a Merlin nest available anywhere? Or Cerulean Warbler? Especially since the Cerulean Warbler nest is described as “unique among warblers” (p. 432). A little more information from the authors on this selection process would have been helpful. The authors do say that they selected a range of angles and distance to illustrate the architecture and environment of the nests, and so we see a beautiful close-up of the hanging, pendulous nest of the Bushtit, complete with side entrance, a long shot of the rock crevice nests of Manx Shearwaters, and a lovely side shot of a Brown-crested Flycatcher utilizing a nest hole in a saguaro cactus created by a woodpecker. The photographs come from 150 photographers and over 115, most appearing to be birders or researchers, are credited with donating the photos. Almost all the images are credited with photographer and location in the text, and a back-of-the-book section gives additional photo captions and credits.

Organization

Peterson Field Guide to North American Bird Nests is organized in the usual impeccable Peterson Guide series manner: chapters are clearly separated with stunning illustrations; color-coded bands at the bottom on the page indicate family sections in the Species Accounts and plain white bands indicate chapter titles in the introduction; front and back pages of the book reproduce important identification tools from the introduction–egg shapes and patterns in the front, nest types and range map legend in the map. Plus, a ruler. To find information, you have a fairly complete Table of Contents in the front of the book (it would be totally complete with listings of all those scattered family group accounts and the Sparrow Chart) and an Index of scientific and common names in the back. The book itself is nicely sized, a little too big for all but the largest pocket but perfect for a daypack. It’s a book perfectly made for breeding bird surveying.

Authors

The three authors have brought diverse talents to this project, which, they tell us, started in 2013. Interestingly, two of them work in the field of professional tracking. Casey McFarland is a Senior Tracker and Senior International Evaluator for CyberTracker Conservation and trains professionals and the public around the world. He coauthored the second edition of Mammal Tracks and Sign: A Guide to North American Species (2019) with Mark Elbroch and Bird Feathers: A Guide to North American Species (2010) with S. David Scott. Matthew Monjello is a nature educator, birder, and Registered Maine Guide. David Moskowitz is certified as a Track and Sign Specialist, Trailing Specialist, and Senior Tracker through Cybertracker Conservation, He is also a photographer and writer and his website lists a number of books, articles, and films, including Caribou Rainforest (2018), Wildlife of the Pacific Northwest: Tracking and Identifying Mammals, Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, and Invertebrates (2010), and Wolves in the Land of Salmon (2013).

They have clearly work long and hard on this book, and the lengthy Acknowledgments contain long lists of people who helped in the field and in the research and writing. Many of their sources are listed in the back of the book in a Recommended Reading list and a longer Selected Bibliography. I would be curious, if they decide to do a second edition, how tracking relates to bird nests!

Conclusion

Bird nests are a visible and popular representation of the full and complex lives birds lead and have become a part of our culture in many ways. People are fascinated with their architecture (Avian Architecture: How Birds Design, Engineer, and Build by Peter Goodfellow, PUP, 2011) and with the eggs they protect (The Most Perfect Thing: Inside (and Outside) a Bird’s Egg) by Tim Birkhead, Bloomsbury, 2016) and with their importance in the lives of the birds they see every day (Into the Nest: Intimate Views of the Courting, Parenting, and Family Lives of Familiar Birds by Laura Erickson and Marie Read, Storey, 2015).

The Peterson Field Guide to North American Bird Nests is a wonderful addition to the small cadre of books about bird nests and I think would be an excellent addition to the toolboxes of all North American birders and naturalists. I am very happy that as Houghton Mifflin Harcourt winds down its publication of new birding titles (due to its acquisition by another publishing company and, most probably, the retirement of bird book editor extraordinaire, Lisa White), they have published this unique, fun, information guide. It is definitely one of the best books of 2021, as I said in the American Birding Association Best Books of the Year podcast (with Nate Swick and Frank Izaguirre) and as I wrote in the just published 10,000 Birds roundup of the best of 2021: Best* Bird Books, Binoculars, Bottles** of Booze, and Backpacks*** of the Bygone Year (compiled and written by Mark Garmin–read it!).

Happy Holidays, productive Christmas Bird Counts, and Happy New Year to All!

- Poulin, R. G., L. D. Todd, E. A. Haug, B. A. Millsap, and M. S. Martell (2020). Burrowing Owl (Athene cunicularia), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.burowl.01

Peterson Field Guide to North American Bird Nests (Peterson Field Guides series)

by Casey McFarland, Matthew Monjello, David Moskowitz

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt/Mariner Books, 2021

Paperback, 512 pages, 5 x 1.16 x 8 inches

ISBN-10 0544963385; ISBN-13 978-0544963382

$24.99 (discounts from the usual suspects)

Donna, a fine review and well put together.

I especially admire, in this review and others of yours that I recall, your discussion of “what came before” — the history of earlier guides on the same subjects. That obviously takes a good deal of research and experience. It makes for very interesting reading that other review pieces often don’t cover.