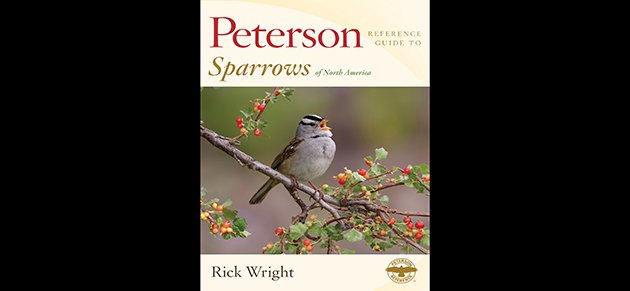

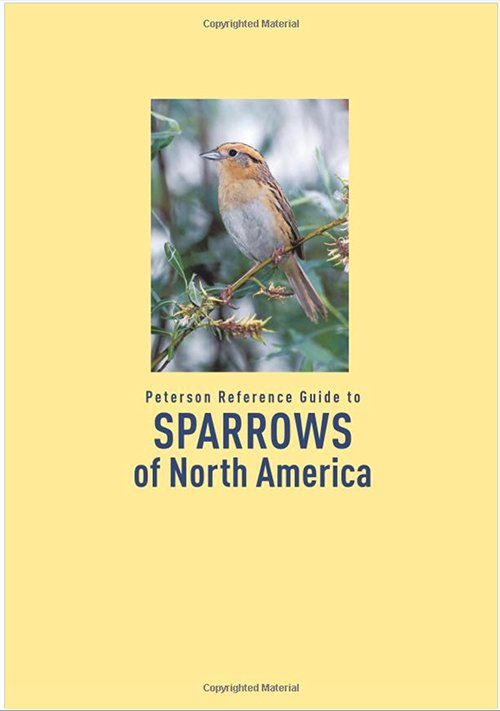

I like sparrows. I like observing them, reading about them, grappling with species and subspecies identification, and even—on a good day—talking about sparrow taxonomy. So, I was very excited when I heard that Rick Wright was writing a book about sparrows, the first treatment of North American sparrows since 2001, possibly the first book about sparrows of North America, depending on your definition of that geographic area. My review copy (well, actually a contributor’s copy—more on that later) was waiting for me when I returned from the ABA birding tour of Thailand and Malaysia (more on that in a separate post) in early March. As I expected, there is a lot to talk about here. The Peterson Reference Guide to Sparrows of North America by Rick Wright is different in approach from any other bird reference book I’ve used, bursting with expertise about sparrow identification, history, and taxonomy, and profusely illustrated with photographs by Brian E. Small and other photographers, mostly, if not all, birders. This is a reference book with many layers, diverse uses and a distinct personality.

Scope of Book

Peterson Reference Guide to Sparrows of North America covers 61 species of the New World sparrow family Passerellidae that breed in Canada, the United States, and northern Mexico. Or, as Wright states in the Introduction, “This guide treats the passerellid sparrows that are known to breed in zoogeographic North America, or the Nearctic region, from arctic America south to the volcanic belt that crosses Mexico from Jalisco in the west to Veracruz in the east; species found only on Caribbean island are omitted” (p.14).

The book does not include House Sparrow, an Old World sparrow that belongs to a completely different bird family. It also does not include species that were included in the last comprehensive treatment of New World sparrows, Sparrows of the United States and Canada: The Photographic Guide by David Beadle and James Rising (2001)—the longspurs and buntings. These species, once considered ‘allied’ with sparrows (or, vice versa), are now considered to be taxonomically separate (with one exception, Lark Bunting). And, birders might be surprised to see the names of unfamiliar species, like Chestnut-capped Brush Finch, Bridled Sparrow, and Black-chested Sparrow, birds found south of the U.S.-Mexico border. They’re all birds of North America!

Wright does a good job of explaining his decisions on what to include and not include and it’s worth reading this section of the Introduction, titled ‘What is a Sparrow?,’ a couple of times, especially since his taxonomic explanations are much more accessible than the scientific article which he used as the basis for these decisions. This article*, authored by seven evolutionary biologists, used mitochondrial DNA gene sequences to establish generic and species level relationships amongst New World sparrows. Wright also uses the article as the basis for the organization of his species accounts. So we don’t get lost in the new re-arrangements, species covered in the book are listed in the Introduction in taxonomic sequence, grouped together by genus, accompanied by explanations of changes. Read the Introduction!

One additional note before I go on to Species Accounts: Certain common bird names are have been changed, ever so slightly (or maybe in a major way, in depends on your attachment to the apostrophe). Baird’s Sparrow is Baird Sparrow, Bachman’s Sparrow is Bachman Sparrow, Nelson’s Sparrow is Nelson Sparrow…you get the idea. The idea of dropping the possessive, the apostrophe–s, in patronymic bird names is not new. But, it is not official AOS or ABA usage. There is a proposal by ABA’s Ted Floyd before the American Ornithological Committee to discontinue the use of the patronymic, arguing that it is based on a misunderstanding of Latin usage and that it is confusing and antiquated. Rick Wright agrees. It will be interesting to see if the proposal is adopted and this guide becomes the first to employ the new official usage, or if it sparks other bird guide authors to revolt against the system. Personally, I find the lack of an apostrophe-s easy to adapt to in writing, but strange when I say it out loud. Change is hard.

Species Accounts

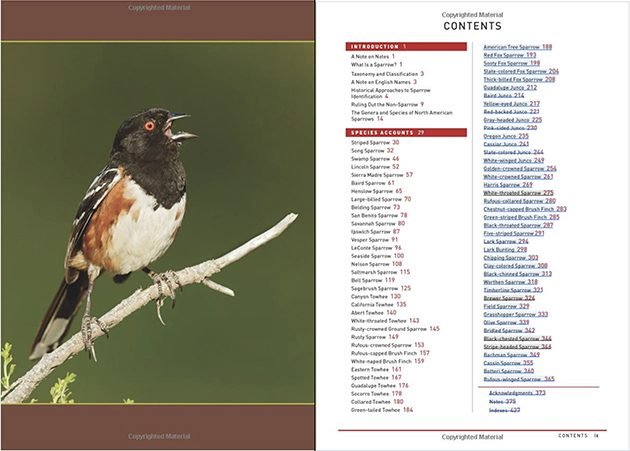

Species Accounts are compromised of 76 species accounts, ranging in length from two pages (e.g., Green-striped Brush Finch, a Mexican endemic) to 14 pages (Song Sparrow, of course). Arrangement follows the taxonomic sequence set out in the Introduction. This means that if you are looking for a specific species, you need to consult the Introduction, or the Table of Contents (also in taxonomic sequence but scannable since it’s all on one page), or the Index of Bird Names, where Species Account pages are set in bold print. So, it may take a minute or two to find the species account for, let’s say, Harris Sparrow (oops, I initially typed out Harris’s Sparrow).

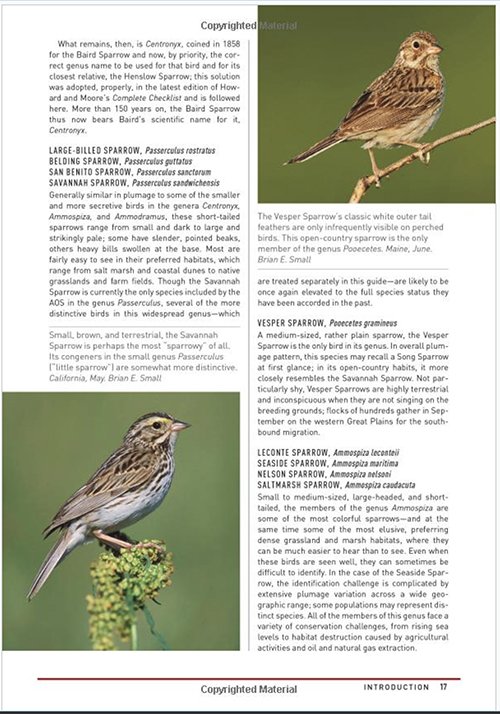

And, yes, that was 76 species accounts, even though the guide covers 61 species. In perhaps the most audacious of several audacious decisions, Rick covers a number of subspecies at the species level, stating that these are distinctive birds. So, there are separate descriptions for birds normally grouped in the Savannah Sparrow, Fox Sparrow, and Dark-eyed Junco complexes. In addition to Savannah Sparrow, for example, there are species accounts for Large-billed, Belding, San Benito, and Ipswich Sparrow.

For some reason, this is treated inconsistently in the listing of species in the Introduction. For example, the section lists Large-billed Sparrow, Belding Sparrow, San Benito Sparrow, and Savannah Sparrow, in that order, but not Ipswich Sparrow, though it is listed in the Table of Contents (see above page). Even more confusing, the Introduction lists Dark-eyed Junco with three other junco species (Guadalupe, Baird, and Yellow-eyed), but there is actually no species account for Dark-eyed Junco per se; rather, there is a separate account for each Junco ‘race’: Red-backed, Gray-headed, Pink-sided, Oregon, Cassiar, Slate-colored, and White-winged. My point here isn’t that I’m opposed to treating these subspecies (or ‘races’) at the species level. I think that’s great; even if these birds remain officially at the subspecies level in the future, it is tremendously helpful to have more information about them. I simply think it is confusing to the user to have them listed in the Table of Contents but not individually in the Introduction.

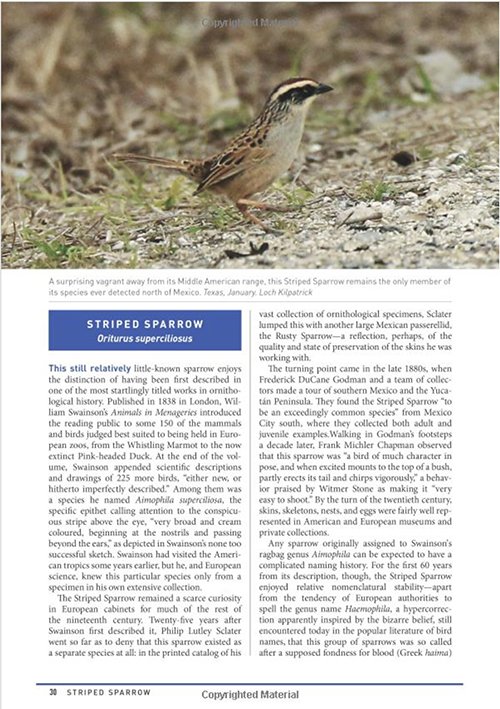

What is in the Species Accounts? History, identification, vocalization, subspecies (if the subspecies are not described separately), and distribution. The latter four items are expected in a reference work about birds, the history is another Rick Wright innovation. More accurately, each account begins with a history of the bird’s relationship with people: who found the first specimen of the species, how it was named–scientifically and in English–plus accounts of mistakes and assumptions early ornithologists may have made about the bird or that we make today in our attributions of discovery, a favorite theme of Wright’s.

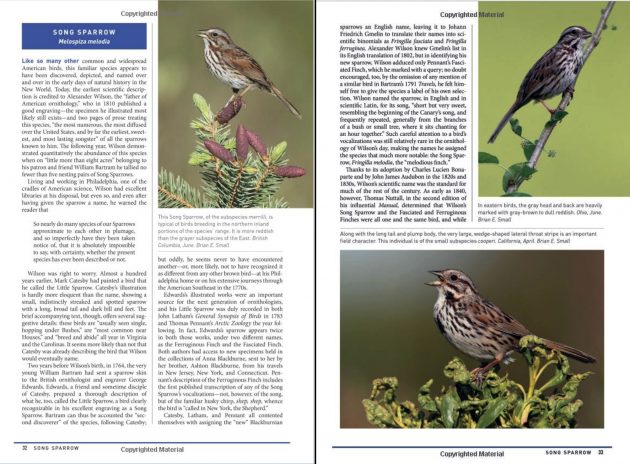

Alexander Wilson, for example, is credited with the first scientific description of Song Sparrow in 1810. Yet, Wright points out, Song Sparrow was first depicted and named (‘Little Sparrow’) by Mark Catesby decades earlier, and then again collected by William Bartram and described and drawn by George Edwards in 1764. And, to make matters more convoluted, the bird that eventually became Song Sparrow was depicted as ‘Ferruginous Finch’ and ‘Fasciated Finch’ in two late 18th-century natural histories.

The histories also trace the naming and placement of each sparrow in AOU (American Ornithologists’ Union) and AOS (its successor organization, American Ornithological Society) checklists and in the ever-changing taxonomic evolutionary scheme of things. In some species accounts, notably Song Sparrow, this text reads as a carefully researched, finely detailed ornithological/historical essay. Other historical treatments are necessarily shorter, reflecting less information available, but even in the 2-page treatment of the endemic Black-chested Sparrow, the history of the bird’s discovery–really a story of international research utilizing a 19th-century photograph–takes up over half of the species account.

As I said above, the ornithological historical approach is a very new way of writing a birding reference book. I like it. I enjoy reading about the history of our passion and my appreciation of birds I observe today is enhanced by knowing how they were found and named in our yesterdays. I am concerned that a new birder might be overwhelmed; numerous names, dates and 19th-century book titles are cited, many expeditions and journeys are discussed, a long list of checklists and Latin terms are reviewed and compared. Then again, this might be a wonderful entry point for some people.

I do want to emphasize that the historical sections do not take away any ‘real estate’ from the more traditional sections on ‘Field Identification’ and ‘Range and Geographic Variation.’ These are equally detailed and documented and the amount of information in each section of each species account is well balanced (the few exceptions being sparrows about which little is known). The 14-page Song Sparrow section, for example, has four pages devoted to history, over four pages on Field Identification, and six pages on Range and Geographic Variation, including extended descriptions of four subspecies groups.

Field Identification

The ‘field identification’ sections are thoroughly detailed, giving plumage details for all forms; extensive notes on identifying the bird in the field by size and structure, bill shape, behavior, habitat, pattern and plumage; and comparisons with similar birds. The text has to be read; details are not laid out in bold headed, brief paragraphs as they are in the Peterson Reference Guide to Woodpeckers of North America. Large photographic images–one-quarter to one-half of a page–illustrate various forms and significant identification features. The photographs complement the text, though they are not totally integrated with the text. (This means that while the captions refer to identification points made in the text, the text does not refer to the photographs.) I appreciate the large size of the photographs, which is helpful in studying smaller, more specific field marks.

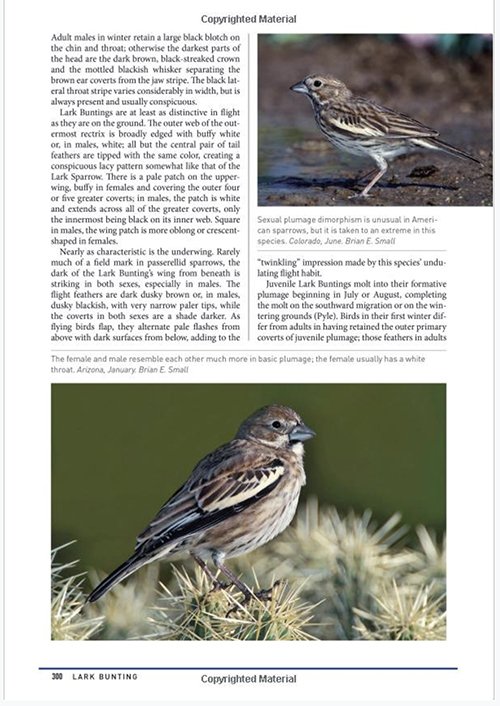

Identification of male and female Lark Buntings

Wright emphasizes the use of “shape and pattern of wing and tail” and size in the identification process. Golden-crowned Sparrows, for example, are “robust, full-bellied, long-tailed, and large-billed” (p.255). Swamp Sparrow is an “oval-bodied, medium-large, long-tailed, short-winged sparrow [that] makes a distinctively dark impression in the field” (p. 48). Behavior is also important. Swamp Sparrows are furtive, White-crowned Sparrows “feed confidently in short grass…” (p. 263), Harris Sparrows are “curious and engaged” (p.271). The finer points of plumage are fully described as well, particularly when Wright is teaching us how to distinguish between two similar looking species, such as Bell Sparrow and Sagebrush Sparrow. Molt sequences are described. Each Field Identification section ends with a description and transliterations of vocalizations, often drawing on historical accounts.

Range and Geographic Variation

The range and specificity of information in this section, which details where the bird resides, breeds and migrates plus how the bird physically differs geographically (subspecies), is incredibly impressive. For example, Wright doesn’t just say that Abert’s Towhee can be found in Utah. He writes, “In Utah, Abert Towhees occur along the Virgin River, and have been recorded as far northeast as the mouth of Zion Canyon” (p. 141). There are no distribution maps, which makes me wonder how much information we miss when we rely only on maps. And, also, whether text alone is the best way of communicating this information. Like the Field Identification sections, utilizing this information requires time and attention.

Photographs

Most of the photographs are by Brian E. Small, whose photographs illustrate many bird guides, including the ABA state series. A number of other photographers are represented, especially for images of the north Mexican birds. Each photograph in the Species Accounts and Introduction is annotated with place, month, and photographer name. I could not find the photographer names for the large, beautiful images used to separate sections, like the Black-throated Sparrow above which introduces the Notes. If I missed this, somewhere, please let me know.

I do wish that there was also a photographic acknowledgements section, with an index to each person’s photographs. This wish is based on self-interest, since I am one of those photographers. I contributed the image of the juvenile Saltmarsh Sparrow on page 117. In return I received a copy of the book, which I figured was o.k. since I normally would receive a review copy. This does represent a small conflict of interest, as does my friendship with Rick Wright. I hope that the nitpicking that I’ve been doing in this review is convincing evidence that my critical eye has not been dulled by the pleasure of seeing my name in print.

Front and Back of the Book Sections

Much of the Introduction has already been discussed, but there are two very important sections that haven’t been mentioned: Wright’s discussion on identification and the section on non-sparrows. Of course, Wright approaches identification from a historical viewpoint. He points out that birders have traditionally been taught to identify sparrows by observing the head, and traces this back to early field guides that could only afford to print illustrations of sparrow heads. He advocates using shape and structure to narrow down possibilities, then using habitat, behavior, and, finally, field marks to narrow down the possibilities even more. Of course, a starting point for narrowing down possibilities is knowing which birds are sparrows and which are female Red-winged Blackbirds, female and juvenile Lazuli Buntings, Pine Siskins, longspurs, cowbirds….is there any brown-plumaged small bird that is not mistaken for a sparrow? Just to be sure, read the section on “Ruling Our the Non-Sparrow.”

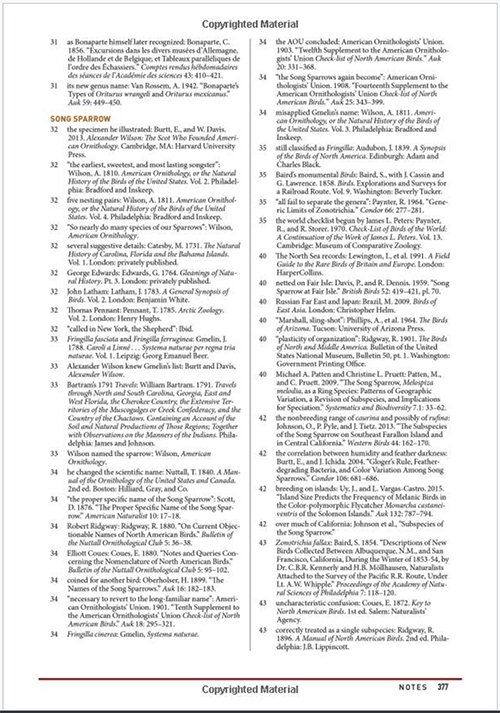

There are three back-of-the-book sections: Acknowledgements (which, sadly, does not include all photographers), Notes, and Indexes. There is no bibliography. The notes section meticulously lists all references by chapter and page in a table-like format. Still, I wish there was also a bibliography listing all monographs, books, and articles alphabetically.

The two indexes, “Index of People Names” and “Index of Bird Names,” make it easy to find people (as in the ornithologists, naturalists, and writers cited throughout the book) and birds. Birds are listed by common name and scientific name (the latter only for birds who have species accounts); only modern-day names are listed (thus, no Little Sparrow). A very nice feature of the bird name index is that common bird names are listed two ways–by complete name, with the first name first, and by family, with the first name following. So, California Towhee can be found in the C section (‘California Towhee’) and in the T section (‘Towhee, California’). Page numbers are bolded to indicate the first page of the species account and italicized to indicate the Notes section. Now, that is how to construct an index!

Author and Conclusion

If you’re familiar with Rick Wright’s work, then the innovations that define the Peterson Reference Guide to Sparrows of North America are not surprising. A fascination with history, words, names, books, and birds and people informs most everything he does. Currently, that includes leading “Birds and Art” tours for VENT, editing the book review section of ABA’s Birding magazine, presenting at festivals and bird clubs, plus writing maybe the most erudite birding blog around, Birding New Jersey (it’s more than New Jersey). Rick has also written the ABA Field Guide to Birds of Arizona and the ABA Field Guide to Birds of New Jersey and is a past beat writer for 10,000 Birds. He has an academic background in German and medieval studies, including a Ph.D. in German, and a Labrador Retriever named Gellert.

Rick Wright has brought ornithological knowledge, meticulous research, the pragmatism of experience in field, a passion for little brown birds, and a certain kind of stubbornness to the conception and writing of the Peterson Reference Guide to Sparrows of North America and produced an exceptional, unique resource. Wright has put his stamp on this book in several ways: an historical approach that traces the relationship between naturalists and sparrows; the adoption of a naming protocol that discontinues the common use of the patronymic; and species accounts that treat selected subspecies in as much depth as accepted species. There is also a strong educational component here. When not relating taxonomic stories, Rick Wright the teacher patiently walks us through simple and knotty identification processes. This is the advantage of a text-heavy guide.

Peterson Reference Guide to Sparrows of North America is a very different book from the most recently published sparrow guides: Sparrows of the United States and Canada: The Photographic Guide by David Beadle and James Rising (PUP, 2001) and A Guide to the Identification and Natural History of the Sparrows of the United States and Canada by James Rising and David Beadle (Academic Press, 1996). (Unfortunately, both books are out-of-print and used copies sell for three figures.) These guides focused on identification facts and are organized in a way that allows you to find these facts quickly. They are excellent identification guides and still useful, though taxonomy and distribution are outdated. And, the 1996 volume includes information on nests and eggs, a topic not covered by the Peterson guide.

Peterson Reference Guide to Sparrows of North America is a book with attitude. It challenges you to become engaged with its subject, and it insists that bird identification be studied within a scope that is larger than wing measurements and bill color. This is not a book for every birder, for example, the birder who is looking for a quick identification guide. It is the book for the birder or naturalist who loves looking at sparrows; who understands that these ‘little brown jobs’ are actually amazing compositions of black, gray, white, ecru, gold, rust, pink, and brown; who values up-to-date taxonomic and geographic information; and who appreciates being part of a larger process of collective discovery. I think every birder who purchases this book, in print or in digital format, and reads it will be happy she/he did.

* Klicka, J. et al. A comprehensive multilocus assessment of sparrow (Aves: Passerellidae) relationships. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 77 (2014) 177–182. The full article is not available free online, but you can read the abstract at the link.

Peterson Reference Guide to Sparrows of North America

by Rick Wright

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, March 2019, 448p.

ISBN-13: 9780547973166; ISBN-10: 0547973160

Hardcover–$35.00; available in ebook formats including Kindle ($19.00); iBook ($19.00); eBook/Google Play ($19.00)

Oh, those LBJ’s! Thanks for an informative review of this new reference book.

Outstanding review of what I’m sure–knowing Rick–is an outstanding book. I can’t wait to see it.