I’ve decided to dedicate this month of March 2019 to wines and beers related to the history of falconry – or hawking – for no other reason than that I’ve recently acquired several bottles adorned with mostly medieval European iconography relating to this “sport of kings”. While the hunting of game with trained birds of prey can be a controversial topic among birders, falconry was a valuable early source of information on birds, and its history, culture, and imagery continue to fascinate bird lovers, as we shall see.

After three visits to southern Italy, followed by a lone excursion to Belgium, we’ll head back south to end our month-long “Grand Tour” of falconry-themed wine and ales in Portugal. Incidentally, Italy, Belgium, and Portugal are among the eighteen countries where falconry is inscribed as a living human heritage by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESC0), attesting to the great heritage of this sport in many parts of the world.

This week’s wine is the 2016 Lobo e Falcão Reserva from the 17th-century estate of Quinta do Casal Branco, located in the Tejo region upriver from Lisbon. While Portugal is perhaps best known to casual drinkers as the home of strong and often sweet fortified wines like port and Madeira, the country in fact produces a wide range of wines, from tart and effervescent vinhos verdes to full-bodied, cellar-worthy reds.

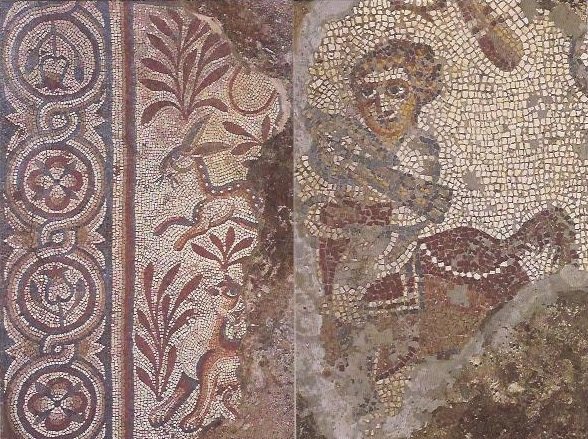

Portugal has a long history of both falconry and winemaking. An 8th-century falconry treatise in Arabic by al-Gitrif ibn Qudama al-Ghassani relates that falconry was practiced by the 5th-century king Euric, whose realm encompassed nearly all of Iberia and initiated three-hundred years of Visigothic rule. A collection of mosaics known as the Mosaico de Cavaleiro in the southeastern town of Mértola dates from the middle of this Visigothic period and contains what is said to be the oldest depiction of falconry in Iberia. Following the fall of the Visigothic kingdom in Portugal and Spain after Islamic conquest in the 8th century, falconry would only became a more firmly fixed Iberian tradition in the hands of the Umayyad rulers of Al-Andalus.

A falconer and his bird from the Mosaico de Cavaleiro in Mértola, possibly the oldest depiction of falconry in Iberia.

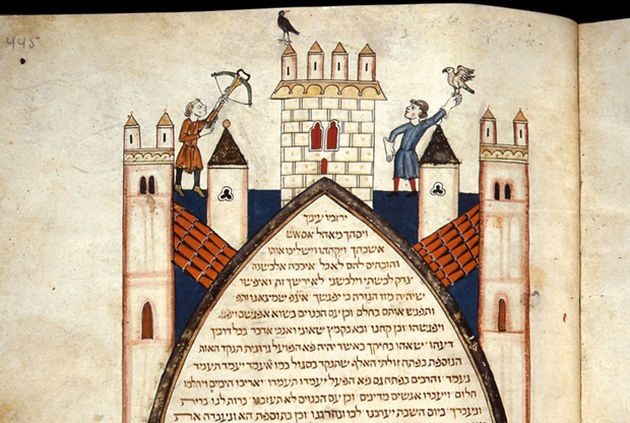

Islamic rule in Portugal established a tradition of religious tolerance uncommon in the rest of Europe, and falconry continued to appear in Christian, Islamic, and Jewish art produced throughout Iberia in the Middle Ages. Colorful birds adorn many of the pages of the so-called Cervera Bible and several captivating miniatures portray hunting scenes with falcons. This gorgeously illuminated Sephardic bible was produced in Catalonia around the beginning of the 14th century but is now housed in the National Library of Portugal in Lisbon.

A falconry scene from the Severa Bible, a Sephardic bible from early 14th-century Spain.

In English, the plays of William Shakespeare abound with the language of the falconer. Similarly, falconry and its literary associations did not go unnoticed by The Bard’s counterpart in Portuguese drama and literature, the playwright and poet Gil Vicente (c. 1465 – c. 1536). An epigraph attributed to Vicente – known as the Trobadour – by Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez in Crónica de una muerte anunciada (Chronicle of a Death Foretold) compares hunting with hawks to the chase of love:

La caza de amor

es de altanería.

(The pursuit of love

is like falconry.)

Portugal was a source of less poetic, practical information on falconry, as well. The Arte da Caça de Altaneria by Diogo Fernandes Ferreira (? – c. 1546) was published in Lisbon in 1616 and remains the best-known treatise on falconry in the Portuguese language. The seafaring Portuguese were also depicted with their falcons abroad as they began building an overseas empire in the 15th century, even in lands as distant as Japan (a nation with its own ancient falconry traditions).

Portuguese merchants in Japan with their hunting companions – a falcon and a leashed perdigueiro Português (Portuguese pointer) – in a detail from a c. 1593 – 1600 byo’bu, or Japanese household folding screen, decorated in the Nanban style. Nanban, meaning “Southern barbarians”, refers to Japanese art of the period of exchange between Japan and Portugal in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, when European traders and missionaries were permitted in Japan for a brief period, before their total exclusion in 1614.

The estate of Quinta do Casal Branco lies outside of the city of Almeirim, along the eastern banks of the Tagus River, the longest waterway of the Iberian Peninsula. Quinta do Casal Branco has been in the family of winemaker José Lobo de Vasconcelos for over two centuries, since 1775. The first half of the estate Lobo e Falcão (“Wolf and Falcon”) label is clearly a tribute to the family’s lupine surname, but whence comes the falcon? The historic Quinta do Casal Branco estate once served as falconry grounds of the Portuguese royal family, where the forebears of Sr. Lobo de Vasconcelos were caretakers, tending to both the royal vineyards and raptors. It’s entirely possible that these birds were employed in vineyard pest control as well; as several modern wineries have rediscovered, falconry is an excellent means by which to deter other animals looking to devour their precious grapes.

A more recent example of the long and beneficial relationship between falconry and winemaking.

José Lobo de Vasconcelos has been the winemaker at Quinta do Casal Branco since 1986, and has spent much of his time experimenting with a range of grapes to find the varietals best suited to the estate and the wines it produces. The estate is also a stud farm for puro sangue Lusitano horses, considered one of the world’s oldest breeds.

The gilded label of Lobo e Falcão, although lovely, portrays a rather improbable scene, with a large falcon poised menacingly in flight above an alarmed and angry wolf.

The Lobo e Falcão 2016 Reserva from Quinto do Casal Branco is the second of only two vintages pressed from their finest grapes, reportedly a blend of Alicante Bouschet, Syrah, Touriga Nacional (the starring fruit in port production), and Cabernet Sauvignon picked from the estate’s oldest, low-yield vines. Fermentation is carried out in lagares, open stone vessels long used in traditional Portuguese winemaking, after which the wine is aged for a year in French oak barrels housed in an 18th-century winery building.

The resulting Reserva radiates a lovely incarnadine glow, with a fruity bouquet imbued with ripe blueberry, floral vanilla, and sprightly but delicate hints of spearmint and white pepper. A juicy and slightly tart palate of woodland berries is tempered by gentle tannins, giving this charming wine a wonderfully suave mouthfeel and a slightly bitter, mocha finish.

Good birding and happy drinking!

Quinta do Casal Branco: Lobo e Falcão Reserva (2016)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Three out of five feathers (Good).

Leave a Comment