Whiskey Month at Birds and Booze:

This January, Birds and Booze at 10,000 Birds is setting its sights on whiskeys all month long. The cold and dreary dead of winter is as good a reason as any to warm up with a restorative dram of uisce, especially after a blustery morning spent scanning flocks of gulls on an icy shore, trudging through woodland snowdrifts in search of new year-birds, or any other half-crazed birding one does in January. But seeing as the month is also bookended by Hogmanay and Burns Night, we’ll gladly take the opportunity to visit– in spirits, at least – the rugged Celtic landscapes of Scotland and Ireland where whiskey was born and – with luck – have a look at the birds that inhabit them.

The dapper European Robin (Erithacus rubescens) is surely one of the best-known birds among the public at large, familiar well beyond its natural range as the celebrated “robin redbreast” of folklore, fable, nursery rhyme, and poetry. But for such a cheery and spritely little bird, the robin’s long list of roles in legend and literature takes some dark and unexpected turns. The jaunty redbreast appears in Norse mythology flying free in the storm-clouds as the sacred companion of Thor, the hammer-wielding god of thunder – yet finds itself imprisoned in the poetry of William Blake, where a caged robin “puts all heaven in a rage” in “Auguries of Innocence”.

A European Robin (Erithacus rubescens) from British Birds and their Eggs by John Maclair Boraston (1909).

Even more grimly, robins serve as undertakers in the “The Babes in the Wood”, a broadside ballad in which the murdered innocents are buried in leaves by well-meaning robins at the decidedly unhappy ending of this traditional tale, first published in 1595. But the story – as well as the funereal associations of European Robin – undoubtedly go back much further, and the robin has been known as the abiding companion of gravediggers for time out of mind.

The cover of “Babes in the Wood” from a c. 1879-1886 edition illustrated by Randolph Caldecott, for whom the medal awarded annually for “most distinguished American picture book for children” is named.

“No burial this pretty pair

From any man receives

Till robin redbreast piously

Covers them with leaves.”

In truth, the churchyard robin – perched hopefully atop the handle of the sexton’s spade, head cocked, and eyeing carefully the ground below – is merely on the lookout for freshly excavated grubs and worms, and is just as likely to accompany planters, ploughmen, and others taking part in less macabre upheavals of the earth. Yet associations with death, burial, and general ill omen persist, culminating in the robin’s appearance as the unlucky victim of “Who Killed Cock Robin?”, an old bedtime story favorite that was arguably the very first murder ballad heard by generations of children.

The still-living Cock Robin.

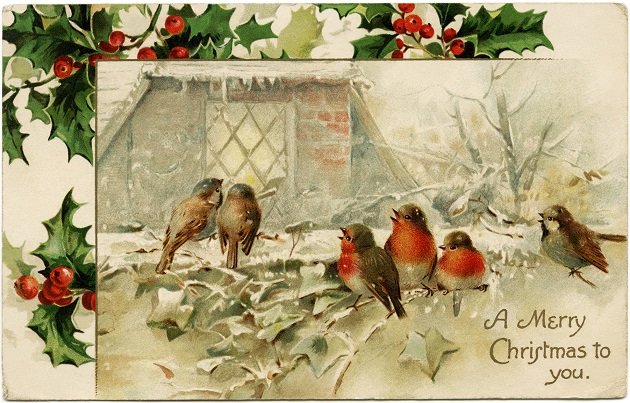

It’s during Christmastime, however, that the image of the robin really comes into its own, and – happily – on much more cheerful terms. With its dashing orange bib, the downright adorable robin makes a merry spot of color on the snowy landscape on countless Yuletide postcards and greeting cards, especially in the British Isles, but also worldwide. It’s an iconographic tradition that dates to Victorian times and continues to this day, though the robin has featured prominently in Christian symbolism for far longer, a fascination undoubtedly inherited even earlier pagan times.

“Dear Robin Redbreast” by English illustrator Margaret Winifred Tarrant.

Even through they subsist on insects during much of the year, European Robins are year-round residents of Britain, and during the colder, gray months of year, their colorful bearing and often audacious presence around humans was not lost on early observers. Writing in the The Ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the County of Warwick of 1678, Willughby and his partner John Ray described the robin’s habits, noting that “In Winter-time to seek food it enters into houses with much confidence, being a very bold bird, sociable and familiar with man”, but also commenting on its more skulking behavior in summer when food was more abundant. It’s likely that people in Europe began associating the robin with midwinter long before there was ever a Christmas to celebrate.

Robins aren’t really quite red though. The old Welsh name for the bird was bron goch – “almost red” – which hits a bit closer to the mark. The robin’s famous red breast really is more of a rusty orange, but the word “orange” wouldn’t enter into English from Old French as a color name until the 1510s (and it was probably even later that the Welsh adopted the cognate oren).

The European Robin was once known in Britain by its old Anglo-Saxon name of “ruddock”, but in the fifteenth century, it became popular to apply personal names to common birds and “robinet” or “robin” – diminutive forms of “Robert” – became the common way to refer to this familiar species.

As for the robin’s famously ruddy plumage, Christian folklore attempts several explanations. In one account, the robin’s breast is forever singed as the compassionate songbird brought water to parched souls in Purgatory. Another pourquoi legend has the ever-pitying bird stained red with the blood of the crucified Christ, either as the robin sang into his ear to comfort him in this final hour of torment, or while yanking off the spines from the crown of thorns. Some even say the plucky little robin was attempting to remove the nails of the Crucifixion itself. In any case, the sacrifice and compassion of this crimson-breasted songbird amidst so much Bibilical bloodletting is strikingly ironic for a bird that so readily engages in gory quarrels with its own kind.

The European Robin as illustrated by Danish naturalist Henrick Grønvold in The Birds of Great Britain and Ireland.

Two more narratives concerning the robin and its red breast pertain to Christmas itself. As one story goes, at the Nativity, the robin was broiled red from fanning the flames of a dying fire struggling to warm the cold manger. And in another telling, the bird was scorched by spreading its wings to shield the infant Jesus from a fire that was blazing too fiercely (the reader with a mind for comedy will visualize these scenes taking place consecutively). As imaginative as these explanations are, there seems to be little agreement as to whether the robin acquired its red breast by blood or by flame (but if you want the real scientific explanation for the robin’s plumage, read this).

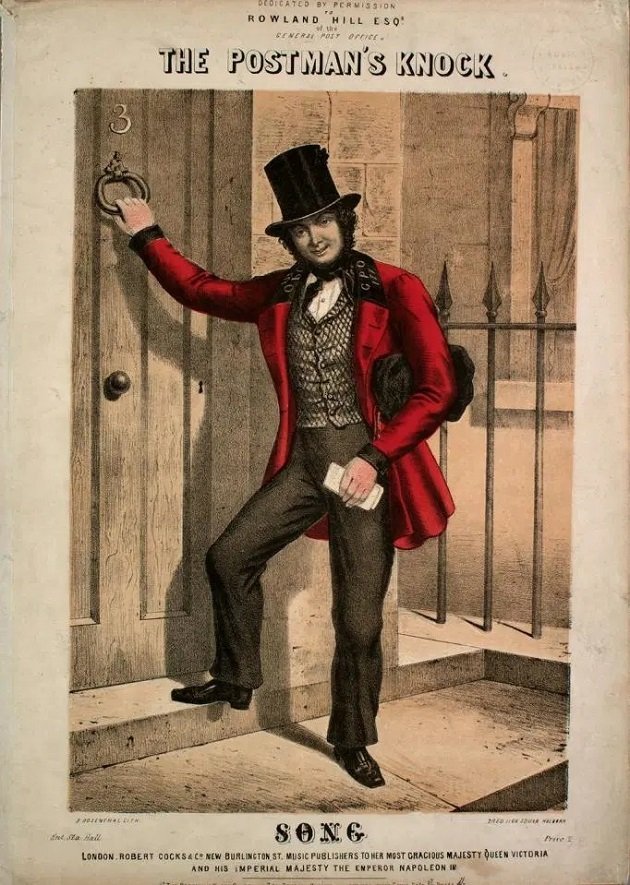

However, the origin of the robin’s indelible association with Christmas is far less fanciful. The most plausible story appears to be the simplest explanation: in mid-nineteenth-century Britain, deliverymen of the Royal Mail wore bright red frockcoats – the color of the very first postal uniforms since 1793 – for which they came be nicknamed “robins”, after the bird.

The robin red “postie” at the door.

The first commercial Christmas greeting cards were introduced in 1843 – commissioned by Sir Henry Cole and illustrated by the academic painter John Callcott Horsley – and became wildly popular amid an overall Victorian revival of Christmas revelry after two centuries of dormancy at the hands of the Puritans and the Enlightenment. After a time, people began to associate the arrival of these novel Christmas cards with the robin red Royal Mailmen who delivered them, and soon, artists began adorning cards with the likeness of robin redbreast.

Given the pervasive presence of the European Robin in history and culture, it’s rather surprising that we don’t encounter the iconic robin more often at Birds and Booze, especially at Christmastime. In fact, its appearance on our featured whiskey this week – the 12-year-old Redbreast Single Pot Still Irish Whiskey – is a surprising first for us. But with its cheery robin on the bottle and spicy, warming flavors, this whiskey is a welcome nip for the end of the holiday season (and today is the tenth day of Christmas, which means that by now, we’ve gone through all the birds of the song “The Twelve Days of Christmas”: 21 individuals in six taxa, for those of you listing at home).

Like all the whiskies produced by Redbreast, the 12-year old expression is a single pot still Irish whiskey, a distilling tradition first developed in Ireland to evade British taxes on malt, and now carried on by only two distilleries in the world (the other being the well-regarded Green Spot). Redbreast is triple distilled at the Midleton Distillery, in County Cork, in copper stills from a blend of malted and unmalted barley, before undergoing maturation in a mix of oak, in former Oloroso sherry barrels from Spain and old bourbon barrels from America.

The Redbreast brand has its origins in W & A Gilbey, a wine importer and distiller founded in London in 1857, which had expanded operations to Dublin by 1861. By 1912, the company was known to be producing a 12-year old whiskey nicknamed “Redbreast” by its chairman, an avid birdwatcher. After two decades of postwar turmoil, Gilbey stopped producing Redbreast whiskey in 1985, before selling the brand to Irish Distillers a year later. The brand was successfully relaunched several years later in 1991 to great acclaim as one of only a few single pot still whiskeys in the world.

The European Robin as depicted by Dutch artist Johannes Gerardus Keulemans.

Like the bird itself, Redbreast whiskey is less red and more of a warm, burnished orange. There’s an immediate hint of nutty sherry on the nose, followed the unmistakable aroma of buttery shortbread. Whispers of holiday fruitcake and spice round out the inviting bouquet, with touches of marmalade, honey, powdered ginger, and nutmeg. At the very end, the aroma lightens up with the musky, floral scent of freshly cut cantaloupe. Redbreast tastes of sweet biscuit upfront, accented with oaky vanilla and almond paste, and finishing spicy with a dash of allspice gumdrops. There’s a remarkably smooth, creamy mouthfeel throughout, making this whiskey an thoroughly enjoyable treat year-round, but especially so in the cold dead of winter.

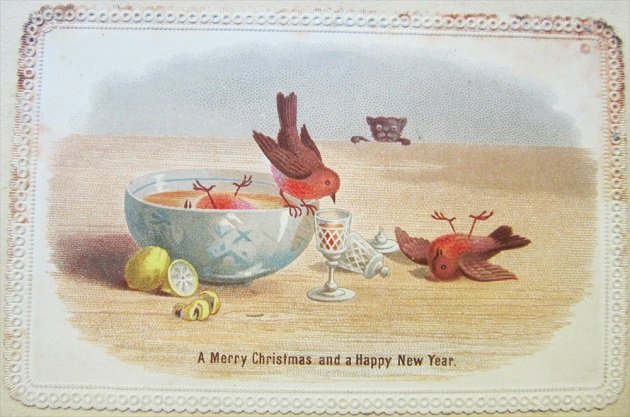

Just don’t overdo it like these reveling robins!

Good birding, happy drinking, and happy New Year!

Redbreast Single Pot Still Irish Whiskey (12-Year)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Five out of five feathers (Outstanding).

While not a whiskey drinker, I loved the history of Robins in children’s stories and on Christmas cards, as well as the explanations for its “red” breast.

I’m glad you enjoyed it, Marjorie – thanks for reading!