“Have you seen the eagles?” If you’re a New York State birder who has been stopped by a state trooper while driving just a smidgeon over the speed limit on the way to a once-in-a-lifetime rarity, you’ve probably heard this question. You’ve explained to the trooper how you’re so excited about seeing this bird and so nervous that it might fly or swim off before you get there that you took your eye off the speedometer, and the trooper asks about a bird he thinks is the rarest of all. And you know he means Bald Eagle, not Golden Eagle, a bird also seen in some areas of New York State but not part of our national culture. Bald Eagle isn’t a rare sight in New York State these days. Visit the Hudson River Valley in winter, where they’ve been holding an EagleFest the first week of February for 21 years, and you’ll see dozens of Bald Eagles perched in large trees near the river, fighting each other over a crow carcass on the ice, flying right over your head. Visit Montezuma Wetlands Complex in mid-April and see 15 active Bald Eagle nests spread out over 50,000 acres. Keep your eye out in my neighborhood in New York City! But if you know your conservation history, you know that the trooper isn’t wrong to be excited, and you share your most recent Bald Eagle sightings, hoping that your shared enthusiasm and awe will bring you a warning and not a speeding ticket, carrying the good vibes to a successful rarity chase.

In 1963 there were 417 known nesting pairs of Bald Eagles in the lower 48 states, down from an approximate population of 400,000 eagles in the 1800s. First there was the human persecution–hunting, trapping, poisoning–then the disastrous effects of DDT, the pesticide indicted by Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. By the 1970s, the Bald Eagle was extirpated from most of the United States east of the Rocky Mountains except the Great Lakes region. Fast forward to 2021: an estimated 71,467 pairs of Bald Eagles nesting in the lower 48 and a total population of 316,708 individuals! * How did we get from edge of extinction to what some think is overabundance? Reports and websites will talk about the protections of the Endangered Species Preservation Act (Bald Eagles south of the 40th parallel were added in 1967) and the banning of DDT in 1972. There is much more. You can’t just snap your fingers and bring birds back, even if they are apex predators, it requires the ingenuity, commitment, and hard work of field workers, biologists, raptor enthusiasts, and government officials. Tina Morris’s memoir/conservation history Return to the Sky: The Surprising Story of How One Woman and Seven Eaglets Helped Restore the Bald Eagle fills in an incredibly important part of this history. It’s an engaging, uplifting narrative, both memoir and conservation history. The amazing thing is, we would never know this story if Tina Morris had not decided to tell it.

I photographed this adult Bald Eagle on the Hudson River in 2014. Thanks, Tina Morris!

Return to the Sky is Morris’s tale of how she pioneered the science and art of ‘hacking’ Bald Eagles on Clark’s Ridge, an isolated cliff within the Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge east of Seneca Falls, New York State. She fed, observed, tracked, and cared for seven eaglets in 1976 (two eaglets) and 1977 (a whopping five eaglets), taking care to do as much as she could from a distance, so the eaglets did not imprint on her. Morris was young, inexperienced, and somewhat lost career-wise, struggles detailed in the few two chapters, but determined to work with Dr. Tom Cade and The Peregrine Project at Cornell University. In a series of fortunate circumstances, some rooted in Morris’s optimistic persistence, some in the luck of it being the 1970’s, the time of the U.S. Bicentennial, she became the one and only field worker in a new project based on The Peregrine Project’s work. “Hacking” is a centuries-old technique for raising and releasing falcons; Cade and his colleagues had taken it from falconry and adapted it to the re-introduction of Peregrine Falcons, another raptor decimated by DDT, into the wild (sometimes the urban wild). Everyone–Cade, the biologists and government policy makers of the NYS DEC (Department of Environmental Conservation) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service–wanted to bring Bald Eagles back to New York State in time for the Bicentennial. No one knew exactly how. Though everyone agreed that Bald Eagles are not Peregrine Falcons, the success of The Peregrine Project offered a possible path, adjusting the hacking method used with the falcons to the needs of young eagles obtained from the Great Lakes (also, later, Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Maryland), where they had not yet been decimated. And so, Tina Morris found herself alone on the top of Clark’s Ridge, camping out for the next few months with her two dogs, responsible for the future of the Bald Eagle in New York State.

Morris’s experiences remind me of Sophie Osborn, who delineated her experiences hacking young falcons for the Peregrine Fund in the first part of Feather Trails: A Journey of Discovery Among Endangered Birds (also published by Chelsea Green in 2024). Only while Osborn was following a perfected strategy in 1991, Morris was figuring things out as she went along fifteen years earlier. The Peregrine Fund staff, particularly Jim Weaver, built the hacking tower and were available for consults, but they were an hour away and this was pre-digital age–no cell phones, no laptops, no instant communication. How to feed the eaglets until they were able to fly, and use their talons and beak to catch food and feed themselves? And would they be able to do these essential life skills without parental instruction? Flying itself took practice, and the eaglets tended to end up stuck in the nearby marsh where Morris had to locate them with the aid of transmitters (again, pre-digital), wade into the muck, figure out a way to re-capture them without injury (to herself and the young eagle). Her solution, using a cut-off blue jeans leg to cover them, astonished experienced raptor experts at a later conference. Like Osborn, Morris continually worried about the safety of her charges, conscious of predators and natural calamities, but here the stakes were much higher. Everyone, she feels, has their eyes on her, everyone is counting on her to find a way to make Bald Eagle hacking viable and repeatable.

There are other threads that run through Morris’s narrative: her unexpected feelings of loneliness and her loving relationship with her dogs, her only companions during those months; her personal reluctance to let herself be a “star” once the project is successful, something she now regrets; and, related, her continual awareness that she was a woman in a field dominated by men. This may seem strange to some readers, but it’s something I totally understand having also started my career in the late 1970’s. The second wave of the women’s movement was just getting started at the time and although icons like Dian Fossey inspired Morris, the reality was that there were few women in ornithological or biological research who were not office managers (one of my first jobs was at a prestigious research university where star scientists (all male) played tennis while their ‘secretaries’ (all women) ran their labs). For Morris, her self-consciousness of being female is personal, not political (she doesn’t get the connection to Seneca Falls, seat of the suffrage movement, till decades later). It manifests in subtle ways that makes her accomplishments even more courageous. Her life and career decisions, described in the latter parts of the book, are emblematic of a time when there was no defined pathway for women scientists and everything was an experiment. Sort of like taking care of seven eaglets.

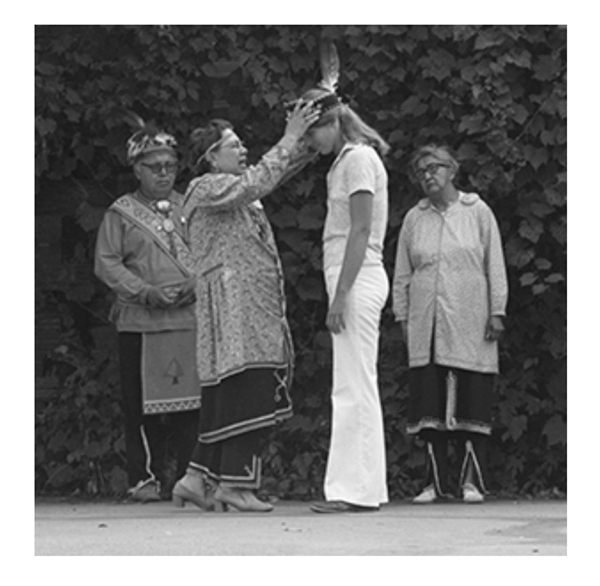

© Cornell University & Tina Morris; Tina Morris being inducted as an honorary member of the Iroquois nation, p. 122.

Three highlights of the book take place decades apart. In 1977, Morris is honored by the Iroquois nation for bringing the Bald Eagle back to their skies in a ceremony that surprises and delights her, partly because of the participation of the Iroquois women. In 2015, Morris discovers that one of her charges, M3, band number 03142, the young eagle she felt most close to, has died. She knew about this eagle, who had fathered 70 Bald Eagles at Hemlock Lake, one of New York’s Finger Lakes, but she didn’t know it was her M3 till it was accidentally run over by a car while eating a kill. M3 was “the most productive and longest living Bald Eagle in known history.”

And then in 2022, Morris returns to Montezuma NWR, the first time since she left Clark’s Ridge in 1977. It’s an experience of shifting memories and personal triumph as Morris reclaims her work and its triumphant aftermath. The refuge is full of eagle’s nests, more proof of success. It turns out that no one knew that the Bald Eagle hacking project, which was handed over to the NYS DEC after its two years with the Peregrine Project and Cornell, started at Montezuma. Or that Tina Morris existed. I don’t know if this is when she started writing her story, but the fact that she did and that we can now read about her two seasons with the Bald Eaglets speaks to the importance of writing personal history. Morris’s story carries so much more weight than I think she anticipated. It shows that discovering one’s passion, at work and in life, doesn’t always follow a straight line; that enthusiasm, a sense of adventure, and imagination triumphs over straight academics; and that one person can make a difference, a cliche, but rooted in reality, as this story shows.

Morris writes in a traditional narrative style with a warm, authentic voice. She starts from childhood, talks abut her life and career after the Bald Eagles, and ends with her return to Montezuma. Several chapters focus on the conservation side of the story, giving it a broader context. I would have liked to know a little more about the growth of the Bald Eagle hacking programs across the U.S. and how her graduate thesis served as a template for them, but I understand the desire to focus on subjects directly related to personal experience. The book is enlivened with several black-and-white photographs of the hacking project, including two great photos of the hacking tower and Morris climbing up the tower. As usual, I’d like more! And I did find more online and in color in uploaded presentations Morris has given to birding organizations (easily found by searching for “Tina Morris” and “return to the sky”). You can also listen to Morris talk about work with the young Bald Eagles on the ABA Podcast. These are both good introductions to the book itself, Return to the Sky: The Surprising Story of How One Woman and Seven Eaglets Helped Restore the Bald Eagle, which I highly recommend.

@Donna L. Schulman; Adult Bald Eagle overseeing nest with eaglet and mom in Sanibel, Florida, January 2025 (different colored backgrounds due to differing photography angles). Although Tina Morris’s project focused on repopulating northeastern states, her graduate thesis describing the hacking techniques became the template for Bald Eagle hacking programs throughout the U.S., including, probably, the one in Florida.

* Axelson, Gustave, More Than 316,000 Bald Eagles Live in the Lower 48, New Estimate Says, March 24, 2021; https://www.allaboutbirds.org/news/new-bald-eagle-population-estimate-usfws/

Return to the Sky: The Surprising Story of How One Woman and Seven Eaglets Helped Restore the Bald Eagle

by Tina Morris

Chelsea Green Publishing, Oct. 2024

208pp.; Hardcover, $28.00

ISBN: 9781645022633

Leave a Comment