The French ornithologist Jean Delacour, writing in The Waterfowl of the World Vol I, describes the Lesser Whitefront as being a “very much prettier bird than other Grey Geese, being dainty and graceful in shape and actions”, adding that “it has long been a favourite in captivity”. The first birds reached London Zoo in 1852, but they didn’t breed, and the first captive breeding took place at Scampston Hall, North Yorkshire, in 1918.

Today Anser erythropus remains a favourite in collections – understandably so, for Delacour was spot on when he described it as being a much prettier bird than other grey geese. Apart from its size, its readily identified at close range by the distinctive yellow eye ring, and the fact that the white frontal patch extends farther up the crown than on the Greater Whitefront. Its voice is similar to its bigger cousin, but is rather higher pitched.

It’s more than 70 years since the first volume of Delacour’s Waterfowl was published. At that time this little goose was still numerous, its breeding range extending all the way from Lapland to the far east of Siberia. Delacour noted that it was a “very abundant” winter visitor to the Caspian Sea, and “still common in Central Siberia, but the far-eastern population, which used to migrate to Japan in large numbers, has been almost destroyed”.

It’s difficult to find definitive population figures for this goose: but the global population is now thought to be around 25,000 individuals, and the breeding distribution much fragmented from what it once was. The Fennoscandian population is close to extinction, numbering no more than 25 pairs. It is officially listed as Vulnerable, with the reason for its decline being high hunting pressure during migration and on its wintering grounds. It’s a difficult bird to protect, as the far more numerous Greater Whitefront is a popular quarry species, and even experienced birdwatchers find it difficult to tell the two species apart.

In a bid to boost the Scandinavian population considerable effort has been made to establish a breeding colony in Sweden using captive-bred birds. Projekt Fjällgås started in 1975, and today the population numbers around 130-140 birds. Continued releases in recent years have allowed the population to grow, but it remains small and fragile. These birds, incidentally, normally winter in the Netherlands and North Germany: the initial releases used Barnacle Geese as foster parents, and these birds migrate to the Netherlands. All the Swedish birds are descended from wild-caught Russian birds, as the original captive-breeding stock was found to be tainted due to cross-breeding with Greenland Whitefronts.

In the past the occasional individual from Projekt Fjällgås has wandered in winter to England, but this past winter witnessed an unprecedented arrival of these delightful little geese. The first to arrive was a party of seven that were first seen at Flamborough Head in Yorkshire on 9 November. According to the Projekt Fjällgås website, “this group turned out to consist of the well-known pair where the male is ringed Green over White, their yearlings and two more adult birds. This group had been reported from Arjeplogsfjällen in August and from the Netherlands on 7 October.”

These birds created a lot of interest here in the UK, but there was more excitement to follow when a party of 24 Lesser Whitefronts, also from Projekt Fjällgås, arrived at the RSPB reserve of Titchwell in Norfolk on 20 January, having presumably flown across the North Sea from Holland. They didn’t linger, as the next day they were relocated at Ken Hill, a nature reserve near Snettisham, where they clearly found conditions to their liking. Remarkably, another flock, of seven birds, arrived at Binham (also in North Norfolk) in mid-February. (Could they be the birds that were first seen in Yorkshire?)

I went to see the Ken Hill flock a couple of times: they were relatively easy to find on their adopted marsh (where I also saw Pinkfooted, Greater Whitefronted, Greylag, Canada and Egyptian geese). They were feeding as a compact flock, not associating with any of the other geese on the reserve. They are delightful little geese, and I enjoyed great views through my telescope, though they were a little too distant for satisfactory photography, as you can see from my not-very-good pictures.

In recent years I’ve seen the Fennoscandian birds many times, as they winter on Lake Kerkini, a large and shallow reservoir close to the Bulgarian birder of North-eastern Greece. There’s no shooting on or around the lake, so it makes a safe wintering ground for them. Successful breeding birds migrate south from Norway’s Valdak Marshes direct to Greece, stopping over on the Hortobágy Plain in Hungary, while failed breeders fly east to Arctic Russia to moult, then migrate south via Kazakhstan. They then continue to Kerkini. Here the first birds arrive at the end of October. Until recently the wintering flock stayed at Kerkini for several weeks before continuing on to the Evros Delta, but in recent years they have remained at Kerkini throughout the winter.

Lesser whitefronted Geese at Lake Kerkini – a photograph by Kostas Papadopoulos, from the website Portal to the Lesser Whitefronted Goose www.piskulka.net

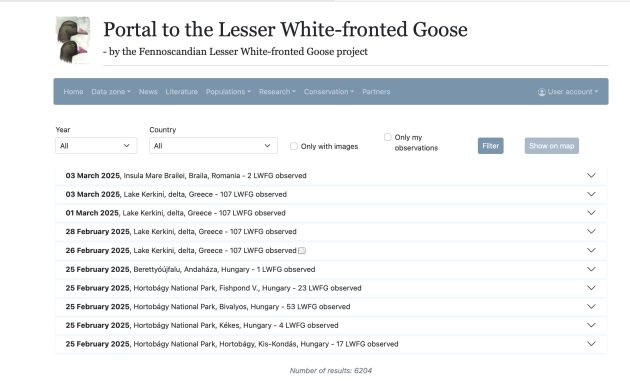

I’m a regular autumn visitor to Kerkini, drawn by the fine birdwatching which is usually combined (in November at least) with fine weather. Seeing the Lesser Whitefronts is a high priority, but it’s always a challenge. The geese tend to both feed and roost far from the shores of the lake, and even with a telescope they can be hard to find, and equally hard to identify for certain, as Greater Whitefronts also winter here. The Lessers are, however, carefully monitored, so if you look at www.piskulka.net (the Portal to the Lesser Whitefronted Goose) you will find an accurate and update count of the flock. If the Portal says that the flock numbers 104 birds, and you can count exactly that number with your scope, you can be pretty confident you’ve found them. Interestingly, my observations suggest that the Lesser Whitefronts rarely mix with their larger cousins that also winter on the lake.

I’ve never managed to get close enough to photograph them satisfactorily, though on occasions I have been near enough to enjoy good views through the telescope, and even (just about!) make out the yellow eye ring. In 2010 the Kerkini flock numbered just 25 individuals, but it recovered to 130 in 2016, before declining again. A year ago it was down to 63, but the good news is that this winter the Kerkini flock was back up to 104 birds, suggesting a good breeding season. Whether the increase can be maintained is debatable, but they are much safer at Kerkini than on the Evros Delta, where goose hunting (for Greater Whitefronts) is allowed.

Latest sightings of the Lesser Whitefronts (as on 6 March 2025)

Unusually cold weather this winter saw the Kerkini birds move away from the lake in early January, but 94 were counted there on 14 January, and 107 on 6 February. The maximum count this winter has been 131 birds. The Portal to the Lesser Whitefronted Goose gives regularly updated accounts as to where the flock is, and how many birds have been counted.

There is, perhaps, a hope that Europe’s Lesser Whitefronts may be staging a modest recovery, a reward for the conservationists in many different countries who both monitor and help protect them. I certainly hope so, as they are very special little birds. Whether the Swedish birds will make a habit of wintering in eastern England remains to be seen, but it would be great if they do return next winter.

This is indeed a delightful grey goose. I really enjoyed looking for and then finally finding my first lesser white-fronted goose in a polder near Strijen in the Netherlands. They are regular in this polder, but that’s not a guarantee you will actually find them. As David’s blog post shows: they move around!

I wrote about LWFGs at Kerkini in this post: https://www.10000birds.com/the-lake-of-beasts-kerkini-greece.htm , with a map of their whereabouts at the lake bed.