Jim Wright is an author and birding columnist. His latest book is The Real James Bond, available as a hardcover, an eBook and an audiobook. For more Bahama Nuthatch information and links, check his blog, https://www.realjamesbond.net. Jim’s first contribution to 10,000 Birds was A Rare Caribbean Parrot on the Brink.

In 2021, the American Ornithological Society announced that it has now classified the Bahama Nuthatch as a distinct species, Sitta insularis. There’s just one problem. Nobody has seen any ever since after Category 5 Hurricane Dorian buffeted the low-lying islands with 200-mph winds for two days in September 2019.

Many ornithologists fear that the long-billed relative of the southeastern United States’ Brown-headed Nuthatch is kaput.

Brown-headed Nuthatch of the southeastern United States. Photo by William K. Hayes.

Brown-headed Nuthatch of the southeastern United States. Photo by William K. Hayes.

“Given the small number of remaining nuthatches and the devastating extent of pine forest damage on Grand Bahama resulting from Hurricane Dorian, one has to suspect that the species is now extinct,” says Professor William K. Hayes of Loma Linda University, who has studied the nuthatch since 2004.

The ornithologist James Bond first found the unusual nuthatch in 1931 on Grand Bahama Island. He noted that this new bird had longer bills and “darker loral and auricular regions” than the mainland Brown-headed Nuthatch, and collected two of them for science. He gave one to his home institution, the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia and the other to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

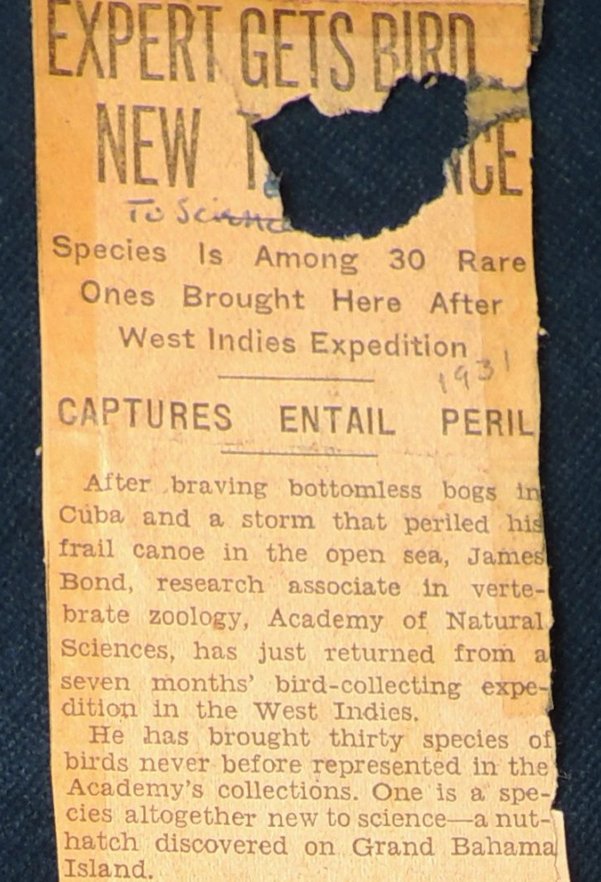

A 1931 daily newspaper article (likely from The Philadelphia Bulletin) reported that Bond “brought back thirty species of birds never before represented in the Academy’s collections. One is a species altogether new to science — a nuthatch discovered on Grand Bahama Island.” Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia, Rare Book Department.

A 1931 daily newspaper article (likely from The Philadelphia Bulletin) reported that Bond “brought back thirty species of birds never before represented in the Academy’s collections. One is a species altogether new to science — a nuthatch discovered on Grand Bahama Island.” Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia, Rare Book Department.

Five years later, when Bond’s landmark Birds of the West Indies was published, he noted prophetically that “hurricanes often take a heavy toll on birdlife, being particularly destructive on the low-lying Bahama Islands.” (British thriller writer Ian Fleming later appropriated the ornithologist’s name for his 007.)

After World War II, the nuthatch began its long slow decline due to habitat loss and invasive species. Developers cut down pine forests to build resorts, and house sparrows and starlings took over the nuthatches’ nesting cavities. Snakes, cats and raccoons preyed on the nuthatches as well.

By 2004, the nuthatch population on Grand Bahama was said to range from a few hundred to several thousand. That’s the year that Professor Hayes and three colleagues postulated that the nuthatch on Grand Bahama and its American cousin were two distinct species because of their physical characteristics and distinctive vocalizations.

But as that theory gained acceptance, the nuthatch became increasingly endangered. A series of devastating hurricanes in 2016, 2017 and 2019 may have sounded its death knell.

“Prior to the last bout of hurricanes, there were only a handful of individuals detected,” says ornithologist Jason Weckstein of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, which holds one of the Bond study skins (seen in the feature photo, special thanks to Matt Halley of the Academy) from 1931. “Either way, it is on the brink of extinction at least. It’s hard to ‘prove’ extinction, as we have seen with the continued push to ‘find’ the Ivory-billed Woodpecker.”

That makes the two study skins that Bond collected even more significant, Weckstein says. “They are the only thing we have to go back to with regard to extinct and in many cases highly endangered species such as this. This may be the only way we learn from our mistakes.”

Ornithologist Paul Sweet of the American Museum of Natural History, which holds the other nuthatch collected by Bond, calls such skins invaluable: “They’re our only physical remaining evidence that these birds ever existed, so if you ever want to know what they looked like, or where they occurred, these specimens are our only evidence, really.”

The Bahama Nuthatch’s home turf is a scrub pine forest on Grand Bahama.

The Bahama Nuthatch’s home turf is a scrub pine forest on Grand Bahama.

Photo by William K. Hayes.

According to Professor Hayes, how species status for the nuthatch changes anything in Caribbean ornithology remains a bit murky.

“It adds to the growing recognition that avian diversity in the Bahamas is much greater than James Bond concluded in his day, and even what ornithologists understood several decades ago,” Hayes says. “When I began looking at bird diversity in The Bahamas, only three endemic species were recognized. Today, that number has more than doubled, with the addition of Bahama Oriole, Bahama Warbler, Inagua Woodstar, and now Bahama Nuthatch. If the nuthatch is now extinct, we’ve lost a species that might have been saved with a greater effort to study and protect it.”

Joseph Wunderle, the editor of Caribbean Ornithology, still holds out a glimmer of hope.

“I’m not convinced yet that the species is extinct,” the ornithologist says. “From a conservation perspective, the recognition of the nuthatch as an endangered endemic species may free up funds for the species. It’s difficult to establish extinction, so multiple post-hurricane surveys are needed.”

Leave a Comment