While The Observer’s Book of Birds was an inspirational little book for me as a small child, it didn’t take me long to want to learn more. My father was a keen reader, and on most Saturday afternoons he would go the local public library. I would often accompany him, and I soon discovered the shelves of natural-history books. There were a couple of books on bird identification, and the first one I borrowed was the Collins Pocket Guide to British Birds, with a text by Richard Fitter and illustrations by R.A.Richardson. Published in 1952, it was the first proper field guide to Britain’s birds. However, instead of the birds being organised by families, here they were divided up by habitat and size, a system that even as an eight-year-old I was unimpressed by.

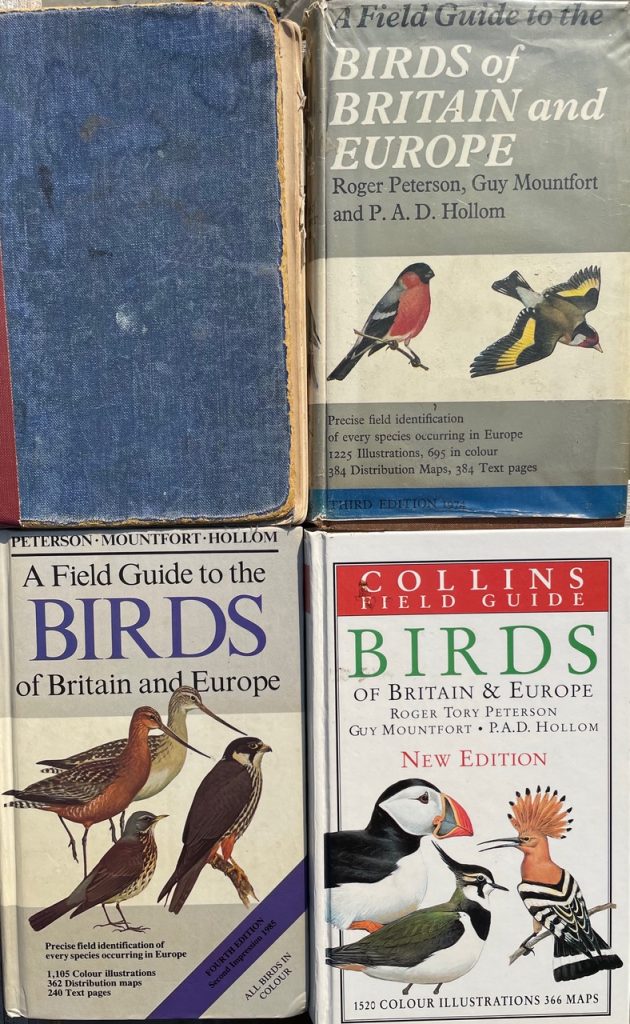

Forty years of the Peterson Field Guide. My original copy, top left, is in desperate need of rebinding

I only borrowed the Collins Pocket Guide once, as when I took it back I discovered what I regarded as a far superior identification guide: A Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe. The text had been written by two Englishmen, Phil Hollom and Guy Mountfort, while the illustrations were by the American artist and ornithologist Roger Tory Peterson. First published 70 years ago, it felt much more modern than the Collins Pocket Guide. I was hugely impressed. In those days you could borrow a book for three weeks, then renew the loan if nobody else had requested it. I repeatedly renewed the library copy until, for my ninth birthday, my parents gave me my own copy. The librarian was delighted to get his book back.

I still have that very edition, now very worn and in need of rebinding. It became, to use a well worn cliché, my Bible, for I read it and studied it continually, while it was my companion on many foreign holidays with my parents. I still recall the excitement of my first trip to Europe, and seeing numerous Buzzards, but were they Common Buzzards or Honey Buzzards? The postage-stamp sized black-and-white maps indicated that both species were possible, while Plate 22 (Buzzards and Small Eagles Overhead), showed that the two were very similar. Many of the plates were in black and white, and this was one of them. Though the text told me that the Honey Buzzard has a tail longer than the Buzzard, with broad black bands near the base, it didn’t mention the very different jizz of the two species. As for the Levant Sparrow Hawk – the text informed that it’s ‘”not distinguishable in the field from Sparrow Hawk except at close quarters”, while there wasn’t even an illustration of it.

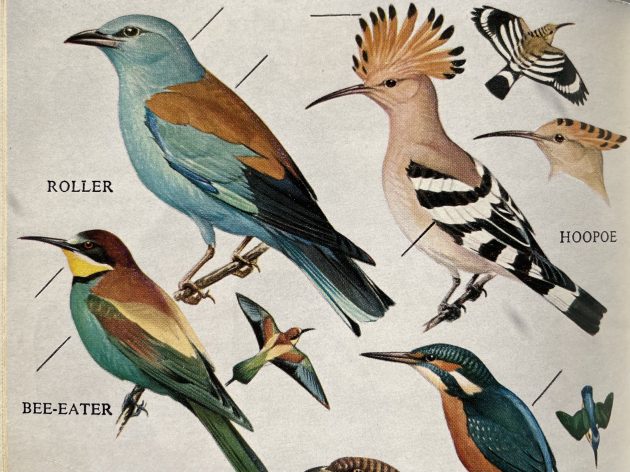

However, despite such failings, the Field Guide (or Peterson, as it came to be known) was brilliant. It was the first pocketable guide to Europe’s birds, so was truly ground-breaking. It was comprehensive, with each species text concise but packed with facts, while Peterson’s art work (with a few exceptions, such as the Honey Buzzard) set a whole new standard for bird illustration. It was a shame that so many of the plates were black and white, but colour printing was then very expensive. At least Plate 46, depicting Roller, Bee-eater, Hoopoe and Kingfisher, was in colour. I used to look at those avian gems and dream of seeing them.

Plate 46: my favourite. I used to dream of seeing such colourful birds

It was Peterson that introduced me to the concept of listing, for it contained a check list of the birds of Europe. “This list” I read, “may be used to record the species you have seen. Accidentals may be entered at the end.” I soon started ticking away. Looking back at what I ticked, I’m impressed to see that I was quite strict with what I checked off. At the age of 11 I was up to 123 species, which may not sound like a lot, but they had all been self-found and identified, with no help from adult observers. There were some good birds, too, such as Marmora’s Warbler (seen on a family holiday to the Italian island of Elba), and Griffon and Egyptian Vultures (another family holiday, this time to Spain).

By the time I was 16 my Field Guide was looking very worn, so I gave it away to Gerry, a young friend I used to take out birdwatching, and replaced it with the 1966 Second Edition. I’ve no idea what happened to that copy, but I replaced it again in 1974 with the revised Third Edition. By this time the Field Guide had been published in 12 different languages, while the English edition had been reprinted with minor revisions no fewer than 14 times. With the exception of Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds (of North America), it had sold more copies than any other book on birds.

The Levant Sparrowhawk was illustrated for the first time in the 1974 3rd edition of Peterson

Though the third edition had indeed been heavily revised, and included an additional 31 species recorded as new vagrants to Europe, the plates remained largely unchanged, though augmented by four new ones of “miscellaneous rarities”. These allowed the Levant Sparrowhawk (note that Sparrowhawk was now one word) to finally have its portrait included. It wasn’t until the 4th enlarged and revised edition in 1983 that all the birds were at last shown in colour. Remarkably, the Field Guide remained in print for over 40 years, with the 5th edition (again revised and enlarged) published in 1993.

The 5th edition of the Peterson Field Guide was published in 1993, 39 years after the first edition. Though the plates remained largely unchanged, the texts had all been rewritten

By now Peterson was showing its age. Since the 4th edition all the plates had been grouped together in the middle of the volume, but (apart from being coloured) they were virtually unchanged from the original 1954 edition. The revised texts were (and still are) excellent, but it was disappointing to see the maps (now printed in red and white rather than black and white) banished to the back of the book. Its coverage, confined just to Europe, looked restricted. In 1954, few British birders had ventured to Europe. Forty years later and many were travelling to the extremes of the Western Palearctic.

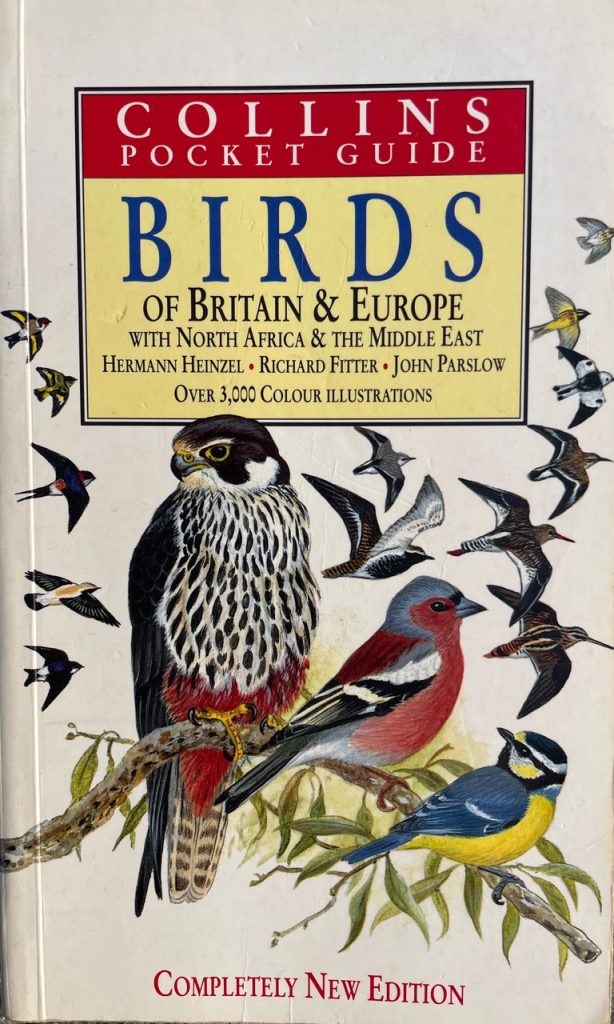

The 5th edition proved to be the last, but the book had remained in print for four decades, and had stood the test of time remarkably well. I have a 5th edition, but it’s pristine and has been little used, for by this time serious rivals had appeared on the scene. The biggest flaw with Peterson was the fact that text and the illustrations didn’t face each other, something that all the later guides rectified. Though several serious competitors had now been punished, arguably the most serious threat to the domination of the Peterson Field Guide was the Collins Pocket Guide Birds of Britain & Europe with North Africa & the Middle East, by Hermann Heinzel, Richard Fitter and John Parslow. First published in 1972, my copy is the 1995 edition, which had been repainted, rewritten, revised and updated. It’s a handsome and compact little book, and with its wider geographical coverage, far more comprehensive than the Peterson Field Guide.

The most serious rival to Peterson: Heinzel’s Birds of Britain & Europe. It geographical coverage was much wider than the Peterson Field Guide

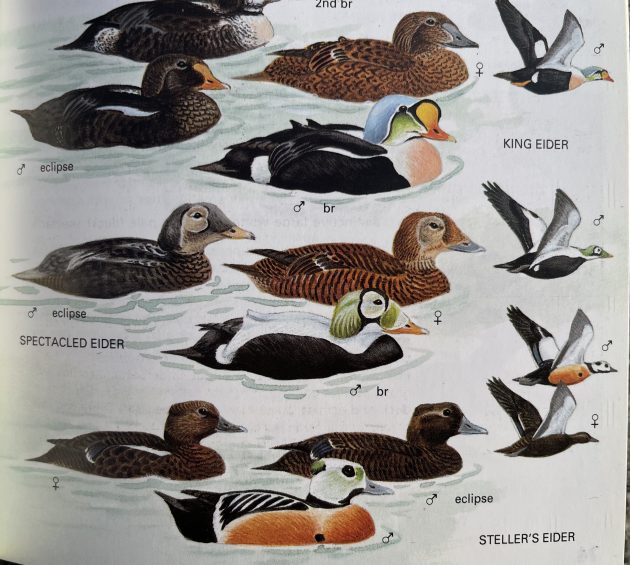

A plate of Eiders, painted by Hermann Heinzel for his Birds of Britain & Europe

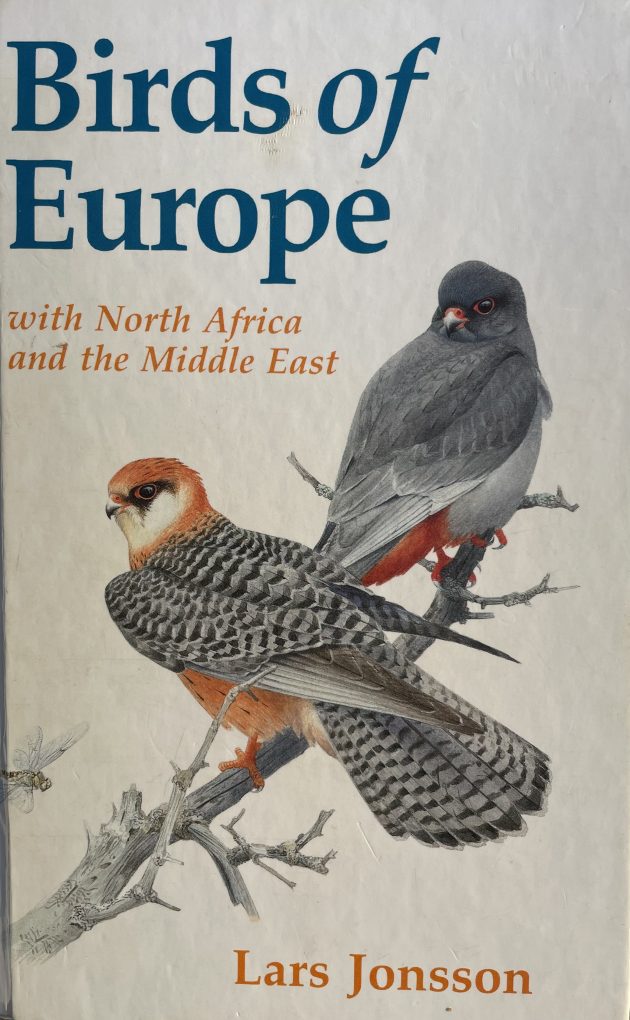

Lars Jonsson’s Birds of Europe remains a firm favourite of mine

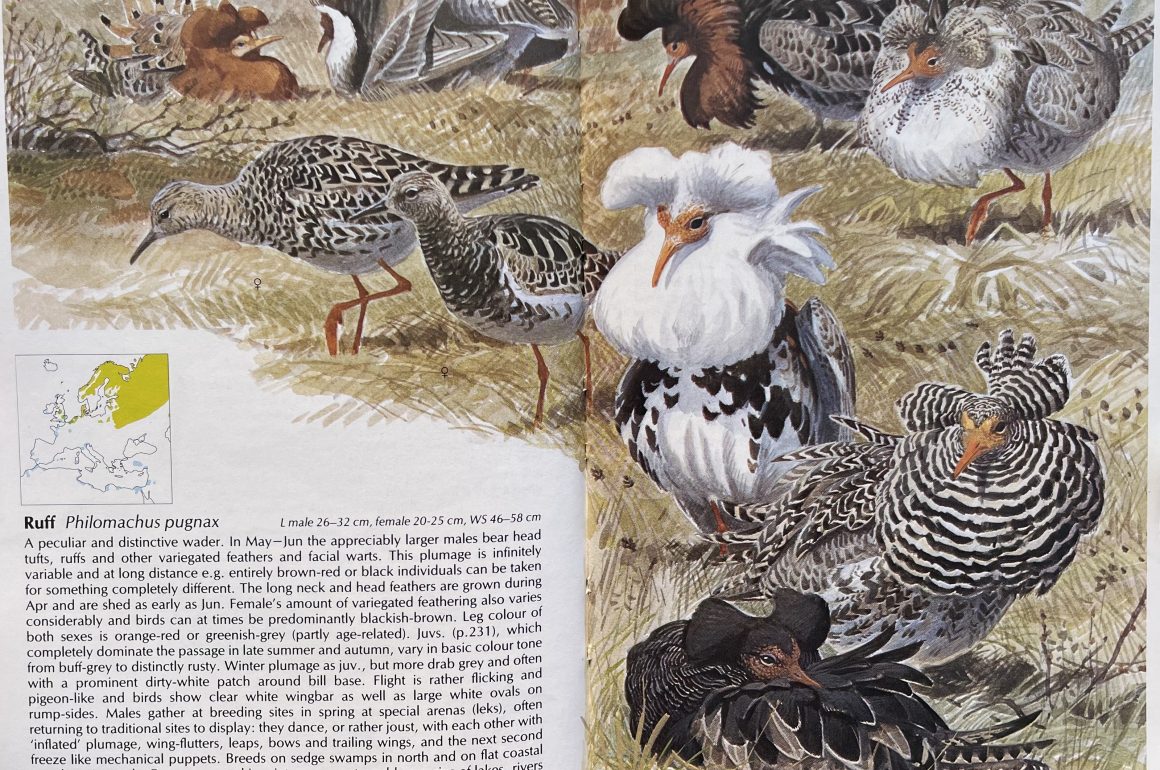

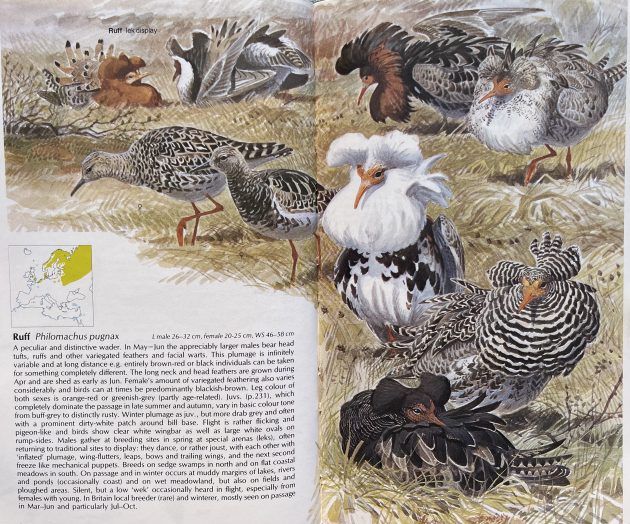

An exquisite painting of lekking Ruffs, from Birds of Europe

However, if I had to name my favourite field guide of the post-Peterson era, I have no hesitation in nominating Birds of Europe with North Africa and the Middle East, by Lars Jonsson, which was first published in English in 1992. (It was originally published in Sweden as Lars Jonsonns Fåglar). Despite being a bit too bulky to fit in the pocket, and with a layout that’s not ideal as a field guide, it’s a sumptuous volume thanks to Jonsson’s terrific paintings that really bring the birds to life. I interviewed Lars shortly after his book had been published, and I rememberer him saying to me that he might not be Europe’s best bird artist, but he was the biggest (at 6ft 6in). I reckoned he was also the best. More than 30 years on, I still delight in thumbing through his book.

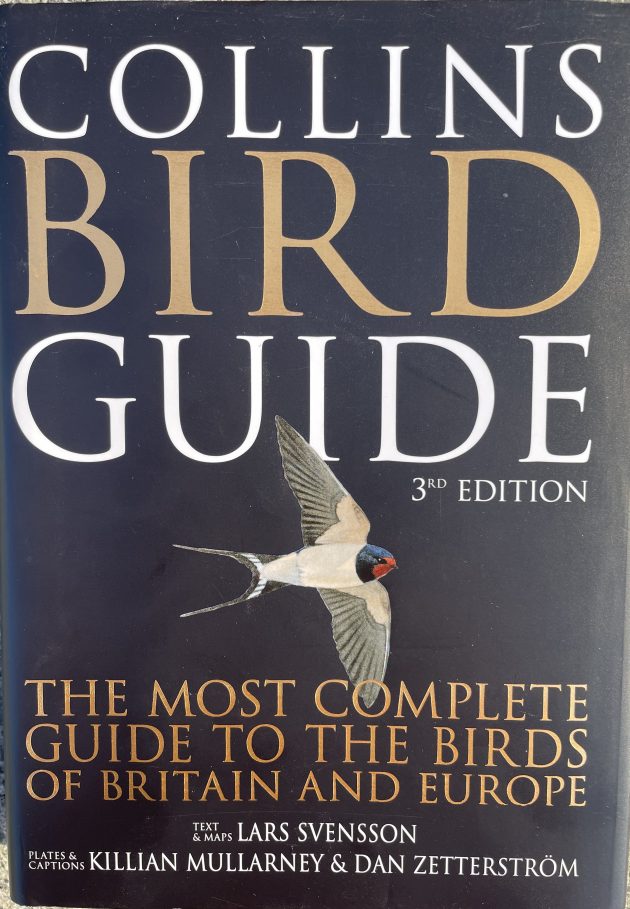

Then, in May 1999, along came the stunning Collins Bird Guide. Written by Lars Svensson (another Swede) with the help of Peter Grant, and with illustrations by Dan Zetterström and Killian Mullarney, it was a hugely impressive work. I remember reviewing it at the time and struggling to find anything I didn’t like about it. Today it’s in its third edition (476 pages, compared with the 388 pages of the first edition) and it’s better than ever, while you can buy it as a hardback, paperback or as digital book for your phone. It is quite simply a fantastic field guide. It faces strong competition from photographic guides, but in my opinion none come close to it. If I was only allowed one bird book, this would be it.

King Eiders, painted by Killian Mullarney for the latest Collins Bird Guide

[Footnote. I was reunited with my original copy of the Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe last year when Gerry, whom I hadn’t seen for over 50 years, joined me for lunch and returned my book. It’s good to have it back. Thank you Gerry.]

Brilliant!

Great topic for a post! And brilliant writing as usual from David …

In the early 80-ies I took a bike trip around the Netherlands with my school buddy Hans. In the Waterland (north of Amsterdam) we saw lekking ruff in several fields. That picture David showed brought back that memory and emotions – that’s a hallmark of good writing. Great start of the weekend!

Thank you for your in-depth review, it is truly captivating!

It’s interesting to see how dated Peterson no looks but it was groundbreaking at the time.

I think that I lost my first copy at Shellness Sheppey!

I never had Jonsson (and buying it from Belgrade in the 1990s was a bit complicated), but had all the others. I’d mention two more, Birds of Britain and Europe by Bruun, Delin & Svensson, and my personal favourite, the namesake by John Gooders – now that was (and still is) a magnificent work.

Another great read David. I too began my birding journey with The Observers Book of Birds plus the Observers Book of Birds Eggs. My bird book became very tatty after a lot of use so I threw it away. Several years afterwards I was in a secondhand bookshop and bought another copy though this time like yourself I had progressed to more advanced works. I just felt out of respect I had to own it again. I am now on the latest Collins and have the app on my phone which is great for a quick listed=n to songs and calls in the field

Hello David,

As a historian and longtime birder who has researched the history of field guides in North America, I enjoyed your post and read it with keen interest. Your comments about the effect Peterson’s plate of “exotic” species echoed something I wrote in an essay a dozen years ago, and which I’ll quote below.

Thanks again and happy birding!

“As a young boy growing up in Ohio during the 1960s, I eagerly read everything I could get my hands on about birds. I wanted to know the names of as many birds as possible, and what they looked like, too. Oliver Singer’s Birds of the World, with Charles Austin’s magnificent, full-color illustrations of species from every family, was one of my mainstays. So, too, was Birds of America, with its detailed species accounts. And field guides—I couldn’t get enough of them. I received my first copy of Roger Tory Peterson’s Field Guide to the Birds in 1967 when I turned 11, and it became a constant resource. I still have that book today, well-thumbed and shelf-worn. I pored over other field guides, also—to the birds of Texas, Europe, Mexico, the West Indies, or whatever else I could find. I would happily spend hours on end reading and re-reading them, committing the birds, their names and their images, to my memory.

“But of all the bird books I studied, my top favorite was Peterson’s Field Guide to Western Birds, the revised edition, published in 1961. Almost immediately after his classic Eastern guide appeared in 1934, Peterson had been approached about doing a similar guide for the West, but waited several years before tackling the project. ‘I dismissed the idea at first,” he wrote, “thinking that although the plan worked out well for eastern North America, it would be almost impossible to do the same thing for the West, where the situation was, it seemed to me, much more complicated.’ Just what Peterson meant by that wasn’t clear to me, but one thing was evident to me as I pored over the 1961 guide: the West had lots more birds than we did in the East. We had, for example, only one hummingbird, the Ruby-throated. But the Western field guide showed 15 of them, tightly bunched together on one plate, with exotic names like ‘Lucifer’s’ and ‘Rivoli’s”’and ‘Calliope.’ Thrashers? We had one, the Brown; out West, the fortunate bird-watcher might find seven others. I was smitten by the thought of doing so—especially the Sage Thrasher, which—as Peterson had rendered it—had this glinting yellow eye and dagger-like bill that gave it a stern, almost challenging, expression, as if it were saying to me, ‘Come on and try to find me—I dare you!’”

“Page after page, plate after plate, species after species—the West seemed way cooler than the East, a veritable birder’s Mecca, with colorful and exotic varieties ripe for the seeing. Warblers; finches; orioles; chickadees and titmice; flycatchers; woodpeckers; hawks and falcons; grouse and other birds—all more varied and diverse than their Eastern counterparts. They captured my imagination. And not only how they appeared, but their names, too, especially those which seemed foreign and mysterious: Phainopepla; Jacana; Pyrrhuloxia; Pauraque; Trogon; Ptarmigan. To me, they were more idyllic than the Knights of the Round Table, more vivid than anything Sinbad or Odysseus had ever encountered in all their wanderings.”