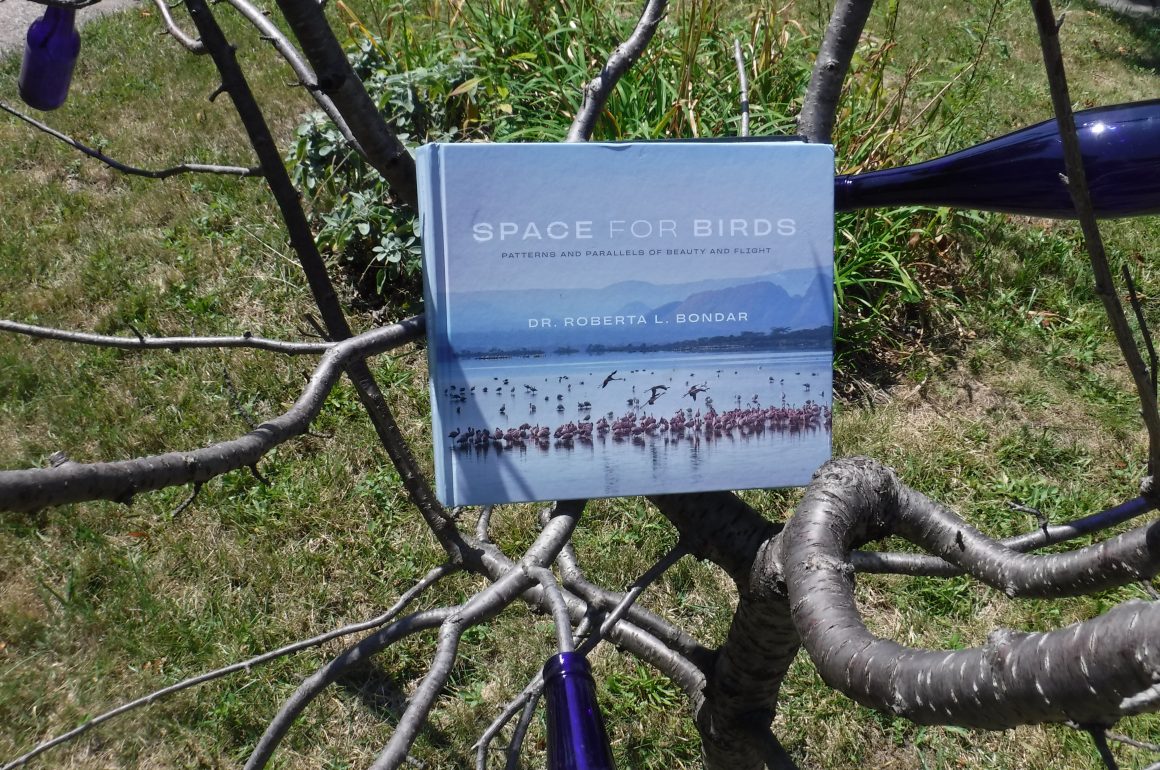

Dr. Roberta L. Bondar’s handsome new book of photographs, Space for Birds: Patterns and Parallels of Beauty and Flight, comes in two halves, but it has several subjects and multiple viewpoints.

Part One of the book concerns the Lesser Flamingo, which has, Dr. Bondar observes, four separate wild populations in the world, in Africa and western India and Pakistan. The biggest such population is in the East African Rift Valley, which hosts the greatest breeding activity on Lake Natron, in an endorheic basin (its water never reaches the sea) part of which is shown below:

(Photo credit: ESRS, NASA Johnson Space Center).

The strangeness of that image is a result of seasonal evaporation exceeding the water inflow, thus allowing salt to concentrate and organisms that thrive in it to prosper. But the other distinctive feature of the photo is that it was taken from outer space, as many photos in the book were (thus, the title).

Indeed, one of the pleasures of the book is that the photos were taken from different points of view: from the ground, like this one, of flamingos feeding at Lake Borgoria National Reserve, also in the Rift Valley (the curved beak being positioned upside down in the water, with the nostrils above the surface):

. . . and from the air, like this one, titled “A flamboyant shoreline,”

. . . and of terrain and environment (like the one of Lake Natron, above), from astronauts on the International Space Station, to which Dr. Bondar provided the coordinates for the images she wanted, as well as earlier NASA missions. The images of Earth from space, she says, “can initiate a change in how we view ourselves and the importance of non-human life.”

The second half of the book is devoted to the Whooping Crane, and the contrast between the flamingo photos in Part One and the whoopers in Part Two (contrast in terms of numbers, that is) is stark. That’s not surprising: as Dr. Bondar notes, Lesser Flamingoes are classified as “near threatened,” with a world population over two million, the Whooping Crane is “endangered,” with a 2023 population estimated at less than a thousand. Thus, while many or most of the flamingoes are shown in flocks of hundreds or thousands (such as this aptly titled “Decision Time”)

. . . the whoopers are shown mostly in pairs, or in pairs with young (such as this one, with the brownish “colt” barely visible to the right of one of its parents):

That photo, like many of the others in Part Two of the book, was taken at the Wood Buffalo National Park, now the main breeding and nesting habitat for the world’s remaining Whooping Cranes. It’s a great wetland (larger in area than Switzerland) of weird beauty, as shown by Dr. Bondar’s photos, but so far up in Canada that the book includes few photos of the Park from outer space — the International Space Station and NASA flight paths don’t cover those far northern latitudes.

In the fall, the whoopers undertake a 29-day, 2,600 mile migration from Canada to southern Texas, where they reside in the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, and eat as many as eighty blue crabs (as well as other plants and animals) a day:

Dr. Bondar, an astronaut herself, a Canadian, is obviously a skilled photographer (and all the photos in the text of this review but the first one are hers). It must be said, though, that as a writer she sometimes wobbles; her gnomic prose can leave a reader scratching his head: “While science satisfies the curiosity, it is only for the moment. While art provokes thought, it, too, is evanescent.” (I’m still trying to figure that one out.)

But she also includes enough factual info to make the reading well worthwhile, stuff that the layperson may not know: for example, whoopers, unlike swans and pelicans (and flamingoes) do not have webbed feet; and (this is marvelous) they have been known to fly up to five miles out of their way to avoid wind turbines.

In 1941, there were only fourteen Whooping Crane adults and two juveniles left in the world. As Dr. Bondar points out, there is hope for a continued revival of the population, though some well-meaning efforts in the past (interbreeding with Sandhill Cranes; efforts to introduce a Florida population) have been mostly fruitless. (This is a story also well-told in one chapter of Peter Matthiessen’s fine 2001 book, The Birds of Heaven: Travels With Cranes.)

Space for Birds is a beautiful book, quite well-designed — except, oddly and annoyingly, for the page numbers, printed in an ink color so faint as to merge with the color of the page itself and be almost unreadable.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Space for Birds: Patterns and Parallels of Beauty and Flight, by Dr. Roberta L. Bondar. Figure 1, Vancouver/Toronto/Berkeley. ISBN 978-1-77327-245-0 hbk). CAD $55, USD $45; 256 pp. Sept. 17, 2024.

Leave a Comment