I write my contributions to 10000 Birds in my east-facing study: it has double glass doors, looking out onto my garden. It’s not just the garden it overlooks, as there are also four bird feeders, a bird bath and a small pond, too. This means that as I write, there are always birds to distract me. Looking out now, I can see several Blue Tits, a couple of Great Tits, a Coal Tit and a single Woodpigeon, but a little earlier there was a pair of Robins (clearly already paired up), several House Sparrows a small flock of Greenfinches. Nothing unusual or unexpected, just my normal visitors.

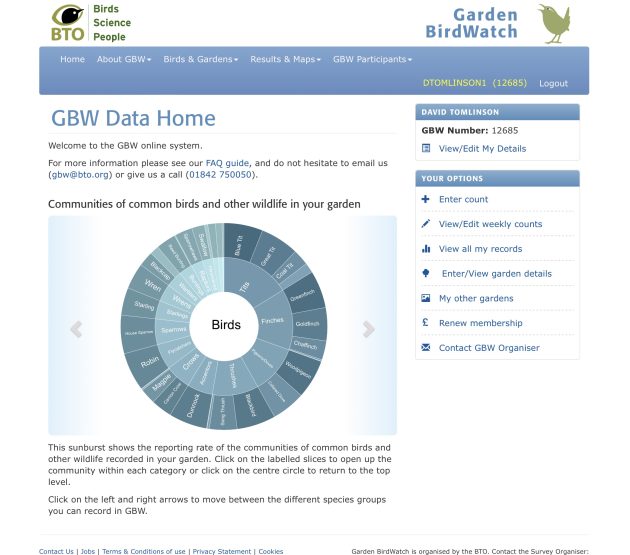

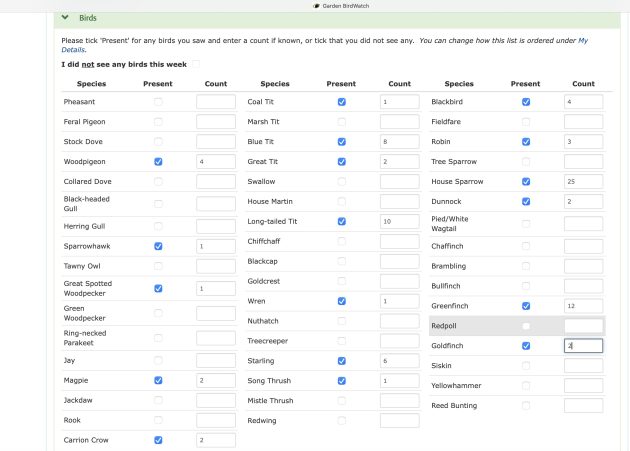

Thirty years ago, the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) launched a major new project, called Garden Birdwatch. I wrote about it at the time for The Daily Telegraph, one of Britain’s biggest-selling newspapers, and I’m pleased to say that my article generated plenty of interest and gained lots of observers, helping getting GB off to a good start. Today the aim and format of Garden Birdwatch has changed little, except that everyone now notes their records on line, rather than on a piece of paper. Records are entered at the end of the recording week (Sunday to Saturday) on a checklist, where you are asked to note both presence and numbers (the most seen at any one time during the day).

Dunnock, photographed in the ivy-covered garden hedge

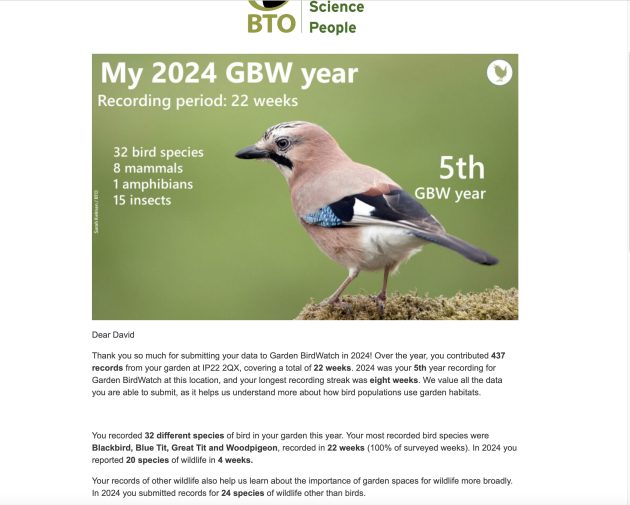

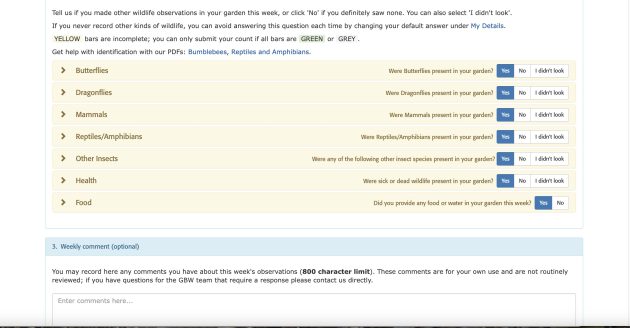

To make the weekly surveys more informative, you can also enter records for mammals, amphibians, reptiles, butterflies, dragonflies and other insects, say whether you came across any sick or dead birds, and note what foods, if any, you provide. It’s all simple stuff, and takes only a few minutes to complete, so there’s no real excuse for not doing it every week of the year, or at least the weeks when you are at home. I’m afraid I failed to do that last year: an email I received today from the BTO reveals my Garden Birdwatching efforts during 2024.

It tells me that I submitted weekly lists on 22 occasions, recording 32 bird species, eight mammals, one amphibian and 15 insects (mainly butterflies). According to the email, 2024 was my 5th year recording for Garden BirdWatch at this location (I moved here five years ago) and my longest recording streak was eight weeks. The message thanked me for my efforts, as “We value all the data you are able to submit, as it helps us understand more about how bird populations use garden habitats.”

I live on the edge of a village, and though I have a large half-acre garden and am bordered to the west by open farmland, my garden isn’t particularly bird rich. My previous house was in a more rural situation, and I’d regularly record over 50 species during then year, and considerably more if you count fly overs (Garden Birdwatch doesn’t). Thus my current garden is a little disappointing, but according to the email, “compared to other rural gardens in East England, your record of 32 bird species puts your garden in the top 30% of gardens in terms of bird diversity”, so I suppose that it’s not too bad. It obviously helps that I’m a practised observer, so know what I’m looking at.

The round-up of my year did tell me that my top species (seen in fewest gardens) were Brown Argus (a butterfly), Banded Demoiselle (a dragonfly) and Reed Bunting. Last summer was a poor one for butterflies, so the Brown Argus, which appeared rather late (on 21 September) was a pleasing sighting. Banded Demoiselles are attractive dragonflies that favour slow-flowing rivers. My nearest river is nearly a mile away, but these are insects that wander, so it’s a species I expect to see in the garden every year. As for the Reed Buntings – they’re garden regulars, appearing in March, at the end of the winter, and visiting daily until the end of April.

Reed Buntings appear reliably in the garden at the end of the winter. This feeder is positioned close to my study window

My most recorded birds were Blackbird, Blue Tit, Great Tit and Woodpigeon, recorded in 100% of surveyed weeks.

Blue Tit – seen every day of the year

A Woodie at the birdbath

A wintering Blackcap, seen in January, was a notable record, and one that sadly hasn’t been repeated this winter. In May there’s usually a cock Blackcap to be heard singing from one of our hedges, and there was last year. Though I heard him daily, I didn’t see him often, as he sang from deep cover.

The 2024 wintering Blackcap

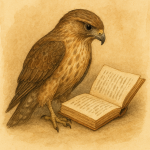

Perhaps the most unusual garden record for 2024 was a Kestrel killing a Woodpigeon. I see the Kestrel frequently, and it occasionally drops on voles that are attracted to fallen seed under my feeders. I didn’t witness the Kestrel kill the pigeon, and only heard about it because my neighbour had spotted, and photographed, the hawk on its prey. I assumed the killer was going to be a Sparrowhawk until I saw my neighbour’s photograph, which clearly depicts a female Kestrel. It was taken on her iPhone, but unfortunately not suitable for reproducing here. According to Andrew Village, writing in his book The Kestrel, “I have seen Kestrels eating Woodpigeons, but never actually killing them, and it is likely that they usually take only dead or dying adults, or immatures.” I suspect that the unfortunate pigeon was an immature.

This Kestrel was photographed through the kitchen window

The BTO does try hard to encourage its observers: “Each year of data is incredibly valuable, revealing how garden bird populations are changing over time. We truly appreciate your participation. Don’t forget to follow us on Bluesky, Facebook and Instagram, and share your wildlife sightings with us and your fellow Garden BirdWatchers.” Well, I don’t do Bluesky, Facebook or Instagram, but I’m happy to support Garden Birdwatch, and will try and submit records for rather more than 22 weeks this year.

Reed bunrings in the garden, nice. They’re common in Holland but I always see them in, guess what, reeds… In Portugal they are commonly seen in winter, also in reedbeds. Never imagined they’d be leaving their biotope for a garden feeder. Also, I vaguely remember reading about garden birding when I lived in the UK (and read The Telegraph). Could it be I read your article back then? What a lovely serendipitous thing that would be.

When we lived in our house, I submitted my garden bird sightings to Cornell University’s Lab of Ornithology’s Project Feeder Watch. I participated for years. That’s the one thing I miss, now that we are living in a condo.