Maharashtra, February 2013

Trying not to inhale so much of the dust cloud that envelops us, I am sporting a bandana tied bank-robber style. A winding track through dense woodlands takes us to the Telia Lake in the southeast of the Tadoba Tiger Reserve in Maharashtra. There’s a Three-striped Palm Squirrel by the side of the track, while Jungle Bush Quails are running across it in front of our Maruti Gypsy, almost the official safari vehicle of India. Finally, the shores of the Telia lie in front of us. As our Gypsy comes to a halt, one Oriental Honey Buzzard is investigating the new arrivals.

The lake consists of a large body of open water, a belt of tall yellow grass (where a big orange cat can blend and disappear if it chooses so) and, all around it, thick forests of predominantly teak, interspersed with thickets of bamboo. On a branch above the road, one Black-winged Kite is scratching its throat and… we brake! There’s a Sloth Bear in tall, dry grass, barely 50 metres from us, but all we can see is a dark, shape-shifting shadow that eventually becomes all but invisible.

We continue slowly between the forest and the grass, watching carefully for any move. There’s a scratch-marked camera trap on a low bridge over a dried stream. Our guide explains that it was discovered by tiger cubs and taken off to play with, hence the claw and tooth marks.

At the far end of the lake stands a tall, dry tree with an eagle that we are struggling to determine and it remains a dark silhouette far too far. Just five metres from us, a metre and a half long and maybe 20 years old Mugger Crocodile is basking in the sun. A mozzie bites me, so I take the “Expedition Plus Insect Repellent” from my rucksack (when I think about it now, any local brand would probably be equally efficient, but they lack the word “expedition” which immediately turns you into a proper explorer) and start spraying my hands and neck. Due to pressure changes during the flight, the bottle started to leak, so I smear the liquid from my fingers over my face… touch my lips, with repulsion feel the disgusting taste of repellent mixed with dust.

Our guide is standing on his seat, scanning the area with binoculars. All of a sudden, in a hushed voice he says one word only: “Tigers!” He has earned his tip.

Somewhere below that mysterious eagle, at the far shore of the lake, lies one Bengal Tiger… and further to the right – two more! We have met the daughters of Telia, the Tigress of the Lake. They are 20 months old, as big as their mother, but not as heavy. The fourth one is missing – she is the adventurer among them. On her own, two months ago, she took down a big, old and experienced Indian Boar, who already had some old tiger claw scars.

Somewhere below that mysterious eagle, at the far shore of the lake, lies one Bengal Tiger… and further to the right – two more! We have met the daughters of Telia, the Tigress of the Lake. They are 20 months old, as big as their mother, but not as heavy. The fourth one is missing – she is the adventurer among them. On her own, two months ago, she took down a big, old and experienced Indian Boar, who already had some old tiger claw scars.

These are my first wild tigers ever! The closer one raises her head, than lies back. The other two are motionless. No, I am not complaining: I am not in a circus and they are not supposed to perform for the tourists. One crocodile swims between us, I can hear the screeching of a Red-wattled Lapwing, on a closer shore are Indian Pond Heron, Little Egret and Little Cormorant, on the far shore are Chital Deer and Lesser Whistling Ducks, above them, an Indian River Tern with its bright-orange bill is patrolling the lake… while I still feel the disgusting taste in my mouth.

The guide continues scanning the far reaches of the lake: “There’s one more tiger.” Four – at one stroke!

We hurry along the dusty track by the shore. Above us, in the treecrowns, are Rufous Treepie and Little Green Bee-eater; on the ground is a Southern Coucal. Two Chitals are about to cross the road, but seeing our speed, they give up.

Telia, copyright © Nitin Bhardwaj

Telia, copyright © Nitin Bhardwaj

Telia, the mistress of the lake and the mother of those cubs, rest at the other side of the cove, about 100 metres from us. The Sun is getting lower, painting both grass and the tigress gold. The Little Egret walks in front of her, a dozen Lesser Whistling Ducks flies noisily low above water and through a flooded grass wades one Black-winged Stilt. The Indian River Tern is checking the scene and, to complete it, the eagle we weren’t able to ID comes closer. With its wings spread, it is an easy one – the Osprey dives into the water, only to emerge wet and empty-clawed. One more circle, one more attempt… with the same result. Telia watches him in half-amusement, then raises and gives a low, bull-like roar, provoking the lapwings to an excited screech, makes a few steps and lies down.

The Great Egret wades the shallows. One Little Ringed Plover stands next to it, while a Red-naped Ibis flies through the field of view of my very dusty Swarovski CLs. Telia yawns, raises and sprays her urine on a dead tree stump, marking her territory. I had no clue females do so, too, but her message is aimed at other passing females, saying that they are not welcome here. She is an excellent mother, managing not only to feed her four large cubs, but their visiting father One-eyed who comes by every now and then (he has two more families and being the good father he is, visits them all regularly, usually around lunch time).

Our mobile phones had no signal inside the reserve, yet, the guides were communicating on some local network, informing each other where the tigers are. We were there in advance and took the best observing position, but our guide soon passed the info and other Gypsies started to arrive, maybe ten of them. Some held only two guests, but most had 4-6, so some 50 tourists were observing the same tigress at the same time. Considering the fact that her lake lies conveniently close to the Moharli Gate, I suppose Telia would be the biggest earner of all the animals of Tadoba.

The tigress rises again and slowly enters the lake, barely 2-3 metres from a croc who is keeping an eye on her. He is too small to be of any threat to an adult tiger – but she can pose a threat to him! The Osprey tries another hunt, finally a successful one, while Telia goes deeper into the water and lies down.

Being just over six years old, she is in her prime and behaves as if the tourists do not exist. She has grown up in the reserve and has no experience of the environment of which tourists would not be a permanent, however boring part of.

Telia, copyright © Nitin Bhardwaj

Telia, copyright © Nitin Bhardwaj

It must be hard to work your fields next to the reserve a big cat for whom you are merely a tailless mouse. In a news report from 2009, the DNA quoted a senior Forest Department official who feared that the poachers must have killed around 20 tigers in the region in just five months. Earlier, a large number of villagers were being killed by tigers: 11 in 2006, 13 in 2007 and more than 26 during 2008. But, in the next year, 2009, only one human was killed by a tiger, leading to a conclusion that all the tigers in the conflict area (practically, the wider reserve buffer zone) have been wiped out. In 2012, the Hindustani Times claimed that from January 2011 to June 2012, a further 9 tigers were killed in the Tadoba buffer zone. At least 274 tigers have died in India in the last four years, more than 70 per cent of them due to poaching.

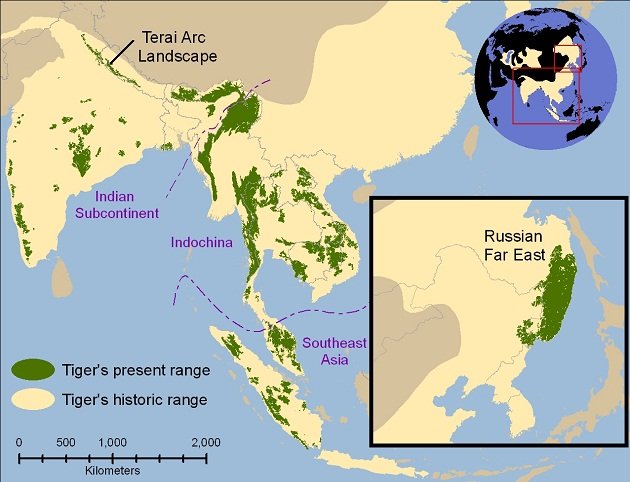

It is estimated that in the year 1900 there were about 100,000 tigers in the world. By the mid-20th century, the Bali Tiger became extinct, followed by the Caspian Tiger around 1970. At that time there were still some 40,000 tigers in the wild. In the 1980-s, another race, the Javan Tiger become extinct and the total numbers halved to somewhat over 20,000. During 1990s, the South China Tiger became extinct in the wild (some still survive in zoos) and the number of extinct races reached four. By the year 2000, the number of tigers in the wild went down to 8,500 and by 2012, it plummeted to a mere 3,200 individuals. In other words, in the last century we lost 97% of these animals and about 40% of their former range (source: WWF).

The problems restricting the number of the biggest of all cats alive include the spread of man-made infrastructure – especially roads and subsequent fragmentation of habitats; destruction of habitat by illegal logging or turning natural forests into commercial wood plantations, as well as illegal killing for vengeance, body parts used in traditional Chinese medicine (such body parts have no medicinal properties) or tiger-bone wine.

Unaware of the cruel statistics, Telia slowly walks through the water disappearing towards the next cove, behind now golden grass of the evening.

Tiger’s historic range in about 1850 (pale yellow) and in 2006 (in green). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Tiger’s historic range in about 1850 (pale yellow) and in 2006 (in green). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The ray of hope comes from the WWF and their Global Tiger Recovery Program: in Sankt Peterburg in 2010, the leaders of all tiger range countries have accepted a common goal to increase their numbers in the wild to 7,000 by the year 2022 and once again extend their range to areas where they once roamed. The tools envisaged for this are improving habitat management (including transboundary reserves), fighting the poachers and collaborating with local communities.

Some results may already be visible. In order to census its tigers, India’s National Tiger Conservation Authority set up 9,700 remote camera traps, which gave the country its most accurate count in decades. “The number of tigers in India has seen a sharp rise to 2,226 tigers from just over 1,400 seven years ago,” Environment Minister Prakash Javadekar said on Tuesday, January 20, 2015. It is a success, despite the heavy burden of poaching and a human-tiger conflict. That, according to IUCN and range country governments, pushes the total population in the world up to about 3,890 animals.

Now with the evidence that the reversal of negative population trend is possible, the next big task ahead is to sustain it and make the 2022 target of 7,000 a reality, hopefully even with a year or two to spare.

Cover photo: Telia, copyright © Nitin Bhardwaj

Find the other stages of the same tour here:

Melghat Tiger Reserve: The Search for the Rarest Owl of India

Leave a Comment