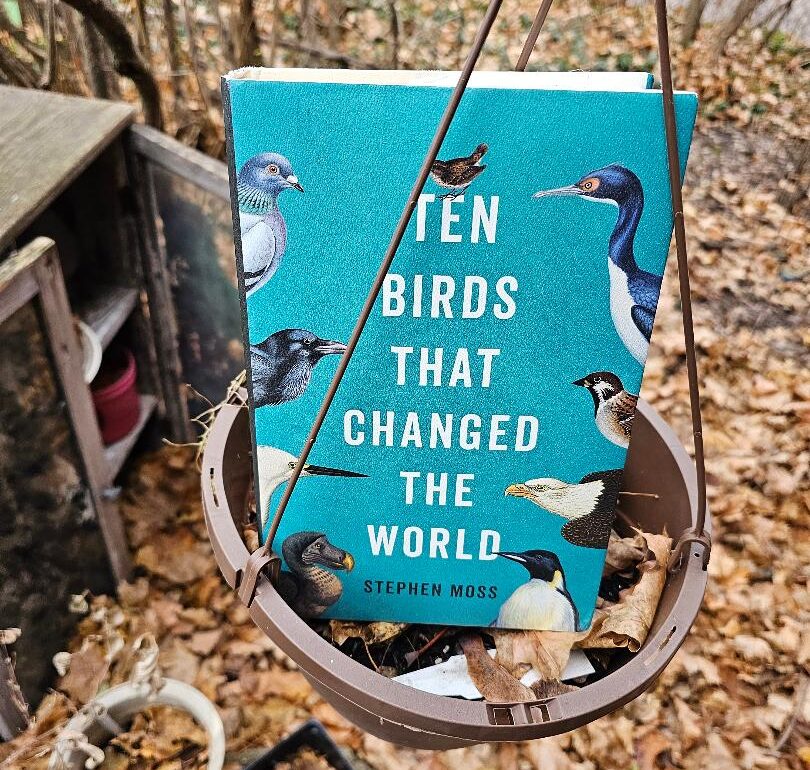

You might think that birds don’t change the world, birds are the world – but by his odd title, Ten Birds That Changed the World, author Stephen Moss means, he says, that birds have, in various ways, led to “paradigm shifts” in human history.

Had it not been for the Wild Turkey, for instance, the first Pilgrims to America, the English ones, would not, possibly, have survived, he says. And pigeons, with their uncanny homing instincts, have played heroic outsized roles in various of our human wars, including the First World War, where a bird named Cher Ami, shot and wounded in the chest, with the loss of the right leg and the sight in one eye, nevertheless made it home, and was credited with saving the lives of 194 Yanks – the “Lost Battalion.”

The book is a grab-bag of facts about the ten birds, mostly culled from other works. (Nothing wrong with that, so long as the sources are credited, as they are.) In his first chapter, on the Raven, Moss is an enthusiastic borrower from Bernd Heinrich’s classic The Mind of the Raven, and in chapter ten (about which more below) a good deal is sourced from a 2022 book, The Bald Eagle, by Jack E. Davis.

There’s a fair amount of etymology, too. At times it seems as though the book’s subject is language and its growth as much as anything else, what with the derivation history of such terms as “guano” (in the chapter about the fecund Guanay Cormorant), “carbon footprint,” and “dodo” (either from the Portuguese for simpleton or fool, or from the Dutch for “fat behinds”). (Odd, then, that Moss doesn’t tell the origin of the term, “cold turkey,” though he does cite the John Lennon song of that name. FYI, the occasionally-reliable www says that the term was invented because the goose-bumps on withdrawing addicts’ flesh resembles that on the necks of turkeys.)

Mostly, Moss’s tidbits make for interesting, if well-trod, stuff. It’s now known that Charles Darwin did not (contrary to what was once a settled idea) assign great importance to the Galapagos birds that came to be called “Darwin’s finches” (though they’re not true finches at all). They were barely mentioned in The Voyage of the Beagle and not at all in On the Origin of Species.

Later it was thought that the widely varying beak sizes and types of those phenotypes inspired Darwin’s insights, a la Newton and his apple. But, as Moss shows, that was all made up – formed by the accretions of later writers and commentators, one after the other: an “accidental, almost random development of the legend.” So, it is a piquant irony that today, as a result of painstaking laboratory and DNA work, we know, as Moss writes, “that Darwin’s finches can indeed illuminate exactly how new species evolve.”

Maybe Moss is right, and birds have changed history. But more often, one would think, it’s the other way around: humans have led to “paradigm shifts” in avian history, and not in a good way. A prime example is the 1958 Chinese campaign to eliminate sparrows, considered pests because they fed on grain. As Moss shows, this “Great Sparrow Campaign” was based on nothing more than the “scientific illiteracy and unbridled power” of one man, Mao Zedong. Hundreds of millions of sparrows were killed, almost to the point of extinction. But Mao had apparently never conceived that sparrows and their chicks fed on insects – insects which, in the absence of their natural predators, destroyed the next year’s rice crop. Millions of Chinese died in the ensuing famine.

As a symbol on all kinds of flags (Mexico, Montenegro, Moldava), and for all sorts of countries (Zambia, Zimbabwe), political parties and organizations (the National Rifle Association), governmental agencies, rock bands, and other things, the Bald Eagle is ubiquitous. Chapter 10 of Moss’s book, which purports to deal with this symbolism, is decidedly weird.

It opens with the ritual, rote denunciation of the forty-fifth American president and all his evil works, thus signaling Moss’s woke virtue. Fine and dandy. He then goes on to show, among other things, how the good, acceptable way to picture the bird is when it faces left (as on the Great Seal of the United States), and the “sinister” way is when it faces right (as used by the America First movement of the early 1940’s, the German Nazi party, and on a t-shirt marketed by Donald Trump’s campaign). Various experts are enlisted in support of this idea. What claptrap.

“Today,” Moss somberly concludes, “we are still faced with the thorny issue of whether the eagle is a positive or negative symbol.” We? I’ve already got a couple of other things to agonize about: maybe I’ll pass on that particular “thorny issue.”

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Ten Birds That Changed the World. By Stephen Moss. Basic Books, New York, $30 U.S., CAN $38.00. September 12, 2023. ISBN: 9781541604469 (hardcover); ISBN 9781541604476 (ebook).

A great review. I always feel a bit guilty when reading reviews of bird books as they tend to be so positive (which also makes for a slightly boring read). No such guilt for me here.