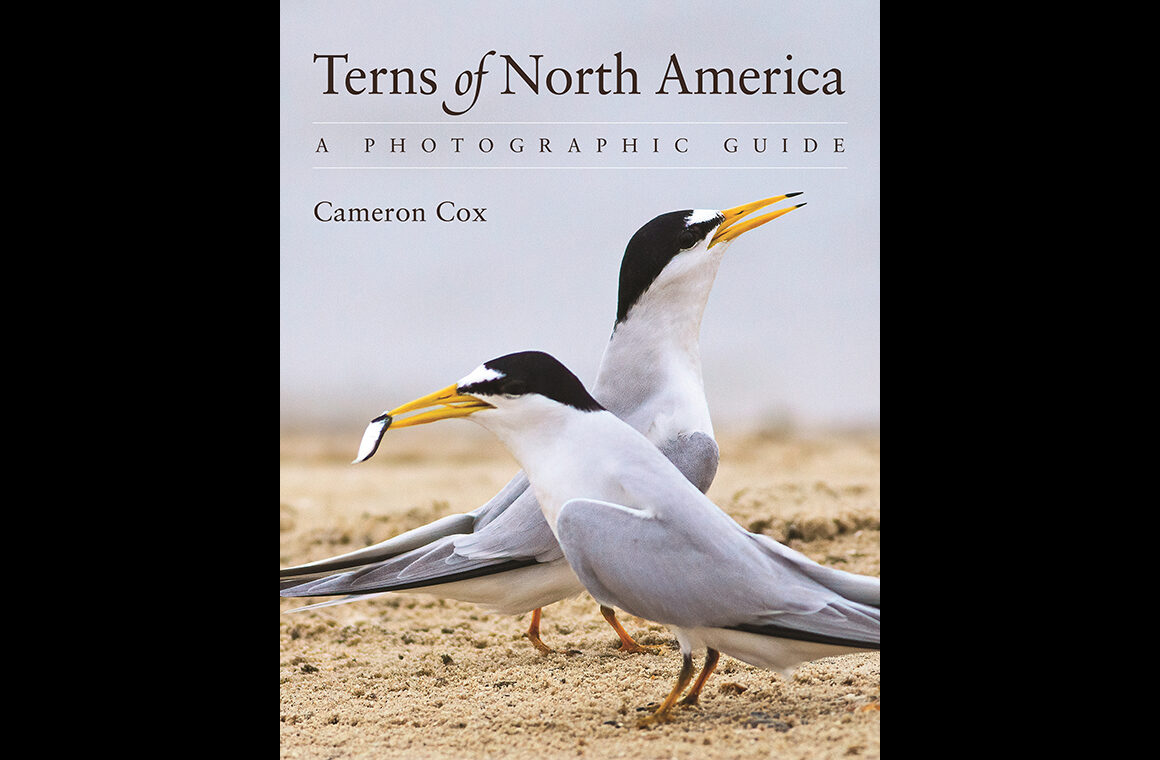

Tern lovers rejoice! A new book about the angelic-looking, identification-stumping birds of the oceans, rivers, and marshes has finally been published! And it’s fantastic. Terns are too often considered the baby brothers and sisters of gulls, and if you don’t agree, take a look at the number of books written about gulls (at least four in recent years) and then try to remember the last book you read about terns of North America. That would be Terns of Europe and North America by Klaus Malling Olsen and Hans Larsson, published in 1995, another fantastic book, but out-of-print and in need of an update. Terns of North America: A Photographic Guide by Cameron Cox takes a purely photographic approach to learning how to identify terns, using hundreds of images (over 325) to discuss which key features to look for at which times of year, which periods of molt and age; the guide and updates tern taxonomy and discusses the knotty questions of how to distinguish apart like-looking species. It’s also a beautiful book to look through.

Terns of North America covers 19 species of terns, noddies, and skimmers that breed and are regular vagrants in the United States and Canada (like many books titled “North America” the geographical coverage stops at the northern end of the Mexico border). Interestingly, Large-billed Tern is not included because “its history of vagrancy is far less recent than that of Whiskered Tern.” I’m assuming the guide was written and edited before two Large-billed Terns showed up in Florida this year; Cox covers his bases by commenting that it’s “an unmistakable species…the only thing that really needs to be said about Large-billed Tern is that if you happen to see a big tern with a huge yellow bill and a Sabine’s Gull-like wing pattern in North America, you are having a really good day” (p. 1). (This is something I’ll keep in mind when I travel to southwest Florida in the near future). Taxonomically, the guide follows Clement’s Checklist, the taxonomy used by eBird, though Cox also brings in other taxonomic opinions for some species, notably Sandwich Tern.

Species Accounts

The Species Accounts are organized by subfamily and genus; the exact order has been modified to make it easier for the user. For example, Noddy and Skimmer accounts are in the back of the book, though according to the 2023 version of Clements, they come before terns, which makes sense since most birders will be using the book to study terns, Skimmer identification in particular is obvious. There are 11 chapters with dual titles: Large Terns: Genus Hydroprogne; Crested Terns: Genus Thalasseus; Tricky Thalasseus; Upland Terns: Genus Gelochelidon; Medium-sized Terns: Genus Sterna; Sterna Tern Identification: Little Terns: Genus Sternula; Marsh Terns: Genus Chlidonias; Pelagic Terns: Genus Onychoprion; Noddies: Genus Anous; Skimmers: Genus Rynchops. Note that these are not all species accounts! Two chapters dig more deeply into the intricacies of subspecies, hybrid, and Sterna (a group that includes Forster’s, Common, Roseate, and Arctic Terns) identification. The dual titles again reflect an effort to make the book accessible to all birders while maintaining a scientific understructure.

Chapters begin with background information: meaning of the genus name, distribution of species worldwide, distribution and range in North America, and shared traits. The two identification chapters begin with an explanation of why the chapter is in the book. I really like the dark-blue text boxes used to delineate these introductory sections; they help the browsing user find the right chapter and give some relief from the nonstop photos and text. The number of pages and photographs allocated to each species varies, depending on difficulty of identification and distribution in North America. White-winged and Whiskered Terns, for example, are rare vagrants and are covered in four pages each. Black Tern, the third Marsh Tern, gets nine pages. Common Tern, the tern to know if you’re going to identify other Sterna terns, is allocated 14 pages (not including the material in the Sterna identification chapter). It is tough to compare coverage, though, since photographs take up a lot of page real estate, and if a whole page is given over to a stunning photo of a breeding adult Arctic Tern, I’m not going to complain.

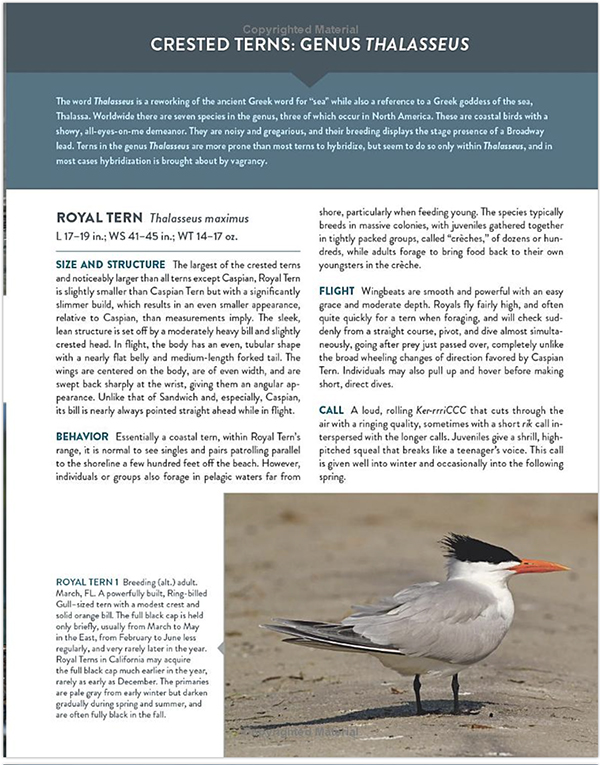

Each Species Account begins with common and scientific name, measurements (length, wingspan, weight) and text paragraphs on Size and Structure, Behavior, Flight, Call, Range, Species Info, and Plumage Info. There are no range and distributions maps. The text information, however, is very detailed. For Roseate Tern, for example, Cox writes about two “distinct breeding populations” in North America, small numbers of nonbreeding immature terns in the Mid-Atlantic region, and the staging area in September near Cape Cod (p. 107). Species Info is an intriguing section with diverse information on subspecies, conservation status, nesting and other life history facts, inclusion of each subject depending on the species and its aid to identification. Overall, there is little on life history, mating, and nesting if it isn’t an identification factor, and there are no photos of baby birds (that’s me sobbing in the background, though I admit that the immature terns are pretty cute too).

The organization of the text paragraphs is a little odd, I think. They begin on the first page of the species section (see the Royal Tern page reproduced above) and then usually continue after several pages of photographs. For example, for Gull-billed Tern, ‘Size and Structure’ is on page 62 and the remaining text paragraphs are on pages 69 and 70, the last pages of the Gull-billed Tern section. If I had not read the introduction to the book, I might think that ‘Size and Structure’ was the only bit of text to read, and miss Behavior, Flight, etc., only to be surprised when I reached the end of the section–if I reached the end of the section. A lot of people read reference books like this by browsing. I’m not sure why the book is organized this way and I don’t know if this will bother other users. You can make an argument that such an organization integrates the photos into the learning process more effectively. If you have a thought on this, let me know.

Photographs

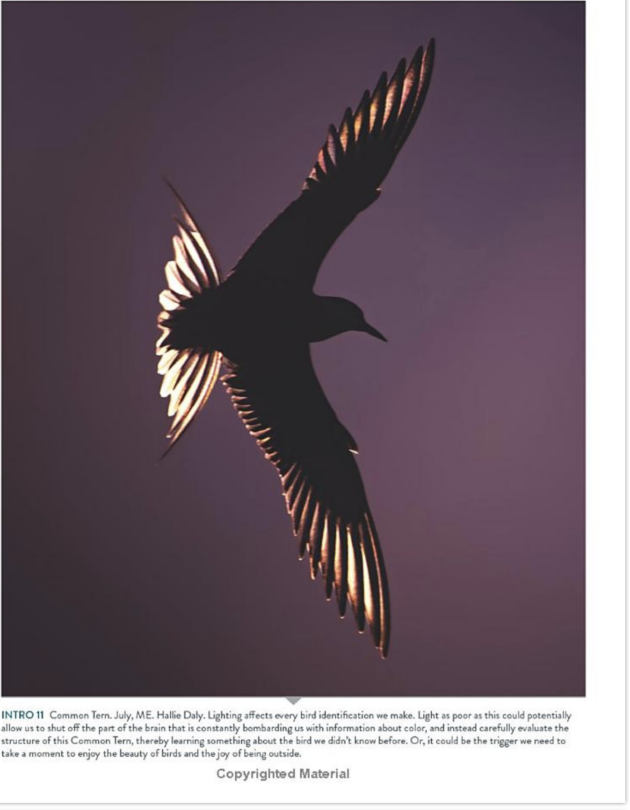

Photographs are core to this guide. They are also an absolute joy. I may be biased because I love photographing terns, but they are elegant (and Elegant), graceful creatures both in the air and on the ground. Most of the photographs are by the author; additional images are by a group of birders and photographers credited in the Acknowledgements, many of whose names will be familiar to birders. I imagine one of the many challenges of creating a photographic guide is selecting photos that impart information; these are not necessarily the sharpest or most beautiful images. Also, it may be difficult to find informative photos; many bird photographers strive for the classic portrait, ignoring behavior, discarding groups. So, I really appreciate the images here, how they clearly present terns, noddies, and skimmers as they are seen in the field while also showing off their beauty. And the quality–sharpness, color reproduction–is excellent. I just thumbed through the book looking for particularly stunning images to cite, but I can’t make up my mind. Maybe by the end of this review.

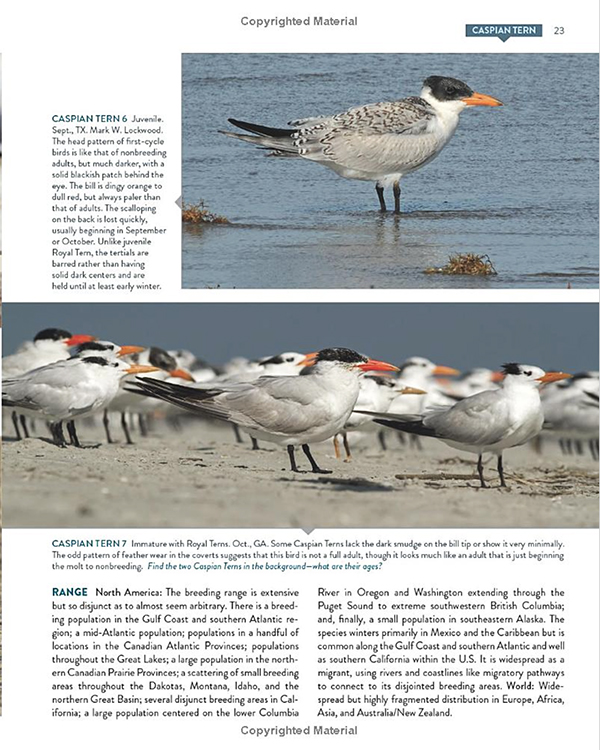

Each photograph has an instructional purpose, which is spelled out in lengthy captions. Each caption begins with the subject bird in bold print followed by its sequence number within the chapter, and then the age and plumage of the subject bird, month and location of the photo, and the name of the photographer if the photo was not taken by the author. Cox says in the introduction that “The bulk of the caption text is merely an attempt to amplify the voice of the image” (p. 17), but I disagree. There is a lot of information here that expands on the text info about plumage, molt, and especially on how to identify terns in a mixed group or when it’s sitting next to a very similar looking tern. Cox also comments on identification traits better seen in the field than in photographs and vice versa, traits seen better in comparison than on a single individual, and the tricks of variable traits. Time of year is an important element in determining identification, so I’m very happy month of photo is stated, as well as location. I see myself spending a lot of time studying these photos and captions in future years, especially June, a happy Tern time on Long Island (N.Y.) beaches.

Other birds in the photos are also identified in the captions, essential for comparison study. I found this occasionally confusing, however, because it’s not always specified which bird is which. Differentiating the Common Tern from the Forster’s Tern or the Elegant Tern from the Royal Tern sometimes required careful reading of the caption. Common Tern 6 (p. 83) for example, directs me to look at the smaller head and shorter legs of the Common Tern on the right (I think) as opposed to the Forster’s Tern on the left (I think). Both birds are sitting on a pipe in the water and the pipe is at a slight diagonal, so it really wasn’t that obvious if the size difference is structural or due to the perspective of the photo. These problems are the exception rather than the norm, and in the end, I learned from my puzzlement, but if a new edition is published, please include more info on which bird is which for those of us who need hand holding. Some of the captions include “quiz questions,” which are interesting exercises but the lack of structure (you need to check the page numbers in the answer key in the back of the book to find them or read the captions very closely) and comprehensiveness make them less of an educational tool than they might be. (Can you find the Caspian Tern quiz in page 23, above?)

Front and Back and Organization of Guide

Reading “Introduction to Terns and Skimmers,” the 18-page introduction to Terns of North America gives the reader background on the tern subfamily, guidelines for tern identification (size, structure, using flocks), and, importantly, detailed descriptions how terns molt and a framework and vocabulary for talking about molt and plumage. Cox is a proponent of the Humphrey and Parkes system for describing molt, as modified by Steve Howell, yet understands that many “casual birders” are unfamiliar with its use, what he calls “the inertia of familiarity” (p. 7). He therefore uses more traditional seasonal terms (breeding, nonbreeding, etc.) in the guide with H&P terms in parentheses. Understanding what these terms mean will totally enhance what you get out of this guide and aid in other types of bird identification (like gulls!). The Introduction also talks briefly about vocalization, lighting, probability, hybrids, migration, conservation, and why life history information is not included except when it aids in identification. The last part of the section outlines Species Accounts components. Surprisingly, the introduction does not include a section on ‘bird topography,’ even though knowing where primary feathers, shoulder bars, secondary bars, the hand, and other physical features are located is required for the identification process.

The back of the book is comprised of answers to the quiz photos, an excellent, four-page Bibliography, and a very brief Index. The Index basically lists pages for species by scientific name and common name, plus references for hybrids. Species Accounts are in bold print, a very important feature since species are not listed in the table of contents.

Reference guides, a book category that includes bird identification guides, are not read sequentially. Birders will open them up in search of one, maybe two, species, and they will want to find them immediately. This demands user keys, pictorial finding aids, indexes, and a good table of contents. Terns of North America has two of these, a decent index and species name tabs in the upper right-hand corner. The latter is of limited use, though, without broader direction. The Table of Contents lists the page numbers for the eleven Species Accounts chapters, plus sections at the front and back of the book, but not where you can find individual species accounts. If I’m looking for Black Tern, where do I go? I can figure out that it’s probably in the Marsh Terns chapter and then go to page 134, where I will thankfully find Black Tern because it’s the first of three species covered in the chapter. Or I can use the Index, which lists “Black” under “Tern.” Or I can browse through the book, looking for the pages that have “Black Tern” in the upper right-hand corner or photos of the distinctive bird. It’s not a LOT of work, but it is work. A table of contents listing species or a pictorial key on the inside front cover would make life much easier for the eager birder in search of identification.

Author

Cameron Cox has written about terns before, in the Peterson Reference Guide to Seawatching: Eastern Waterbirds in Flight, co-authored with Ken Behrens (HMH, 2013). As described in the bio information for that book, he spent his younger years as a “bird bum,” including stints counting hawks at the Cape May Point Hawkwatch. He also worked as an optics product specialist (and has written identification articles for Leica that you can find online), a birding tour guide, served as Photo Quiz master for Birding magazine for a couple of years, and wrote two excellent identification articles for Birding, on “North American peeps” (2008) and American and Eurasian Wigeons in female-type plumages (2005) that can be found in the new American Birding Association Identification Vault. Cameron Cox currently conducts birding workshops and tours through his own company, Avocet Birding Courses.

Conclusion

Terns of North America: A Photographic Guide by Cameron Cox is a wonderful identification guide to a charismatic group of birds rarely covered in species-specific guides. In addition to the 1995 Terns of Europe and North America and the Peterson Reference Guide to Seawatching, already cited, you can read about tern, noddy, and skimmer species in Harrison’s Seabirds: The New Identification Guide (2021), where detailed artwork shows them in flight and standing, in breeding and nonbreeding, 1st summer and 1st winter plumages. This is a great starting point, but nothing compares to the depth and comprehensiveness of description and analysis found in Terns of North America.

The book is worth buying for two chapters alone–the thoughtful sections on Sandwich Tern/Thalasseus taxonomy–that challenging knot involving Eurasian Sandwich Tern, Cayenne Terns, Cabot’s Tern (which Cox has renamed North American Sandwich Tern)–and on Sterna identification. The latter chapter is a photographic tutorial based on a series of individual and comparative photographs, discussing some of the more challenging aspects of distinguishing Arctic Terns from Common Terns from Roseate Terns from Forster’s Terns. Cox insists that this material can be learned, and I hope he’s correct.

Clearly, this book is the product of much thought and work, a distillation and elucidation of many years of observation and study and discussions with other Larophiles. Though I think there are some organizational features that could be improved, it is overall one of the best books of the year and a book that birders, especially those who frequent the oceans, lakes, rivers, and marshes, will want to read, study, and enjoy. And here is one of my favorite photographs, an incredibly lovely backlit Common Tern in flight.

Terns of North America: A Photographic Guide

by Cameron Cox

Princeton Univ. Press, Oct. 2023, 208 pp., size: 7.5 x 9.5 in.

ISBN: 9780691161877

$27.95/£22.00

Leave a Comment