The following picture will show you a landscape feature you may find attractive or even peaceful and nice. A landscape form you will want to visit from time to time specifically for your enjoyment and for a few quiet hours in the fine outdoors. This landscape feature will provide recreation and a rest from a working day’s hustle and haste, so long as you are a non-birder. For birders especially in America, this landscape will soon provide doom, destruction, death, and decay. American birders, brace to receive catastrophe.

What may seem like an ordinary forest might soon be the site of madness, murder, and mayhem. Thankfully, this grim and ghastly outlook is limited to a very specific type of forest, one that is entirely made up of trees.

Okay, this post will provide fair warning: If torment, torture, and terror in birding aren’t your thing, or if you are underage and your parents are watching, just take a last glance at this artistic rendering of a flying Great Tit in low light and then click this post away.

You’ll be forgiven. And you might live to bird another day.

A Great Tit that decided to out-smart the dummy setting of my DSLR. The white dot is the Tit’s evil eye reflecting the light of my lousy built-in flash.

Still here?

The thin red line between bravery and folly is a river of blood, they say.

So here we go, lesson one: learn to read the signs and recognize danger before it recognizes you. If you find yourself in a situation as the one depicted below and it doesn’t make you happy, back off slowly behind a tree downwind and out of sight, then turn around and run. If you are mildly interested, proceed and read the caption.

Despite being taken in Europe, this image exemplifies why forest birding in North America might soon be rated NC-17. Yes, there is a bird in this picture. Of course you have already spotted it. And naturally you know what genus it belongs to. And you are absolutely spot-on right in having finally worked out what this post will be about (lesson 2) …

Treecreeper Identification

The Treecreepers are creepy creatures outside North America. They are essentially moving bits of bark, a patterned composition of brown on brown. And while they are easily identified to genus level, species identification – where necessary – is all I have mentioned in the intro to this post above, and then some.

“Outside North America” and “where necessary”?

I’ll explain.

There are currently 10 species of Treecreepers that form the family Certhiidae, nine in the genus Certhia and an additional oddball in another genus, Salpornis.

The geographic stronghold of the genus Certhia is clearly in South & South-East Asia, with only three species occurring outside that area:

– Common Treecreeper, Certhia familiaris in much of Europe and northern Asia

– Short-toed Treecreeper, Certhia brachydactyla in mainland western, central and south-eastern

Europe and the Maghreb (but expletively explicitly not the UK)

– Brown Creeper, Certhia americana from North America all the way down to Central America*

There has always been and still is considerable controversy surrounding the two Treecreeper species occurring in Europe. Some ill-informed American wannabe birder pretended to “clear things up” recently – causing concerns and chaos in the process – but thankfully rational and science-based heads in Germany prevailed and delivered the hard facts in the case. Of course, and as usual, the UK birders are late to the party and just won’t get it.

If we ignore the chilling challenges Certhia creates in S & SE Asia [this region is full of wonderfully weird and wicked bird groups anyway, so the Treecreepers fit into the region’s birding routine like a gnatcatcher into its nest], we will notice that mainland Europe is currently the only region that is experiencing identification issues with the Treecreepers.

For the rest of the northern hemisphere, the identification to genus level is where the Treecreeper challenge stops being a challenge, and frankly telling a Treecreeper from any other bird isn’t really a challenge in the first place. North America may currently feel very smug, safe and sound.

This may change.

David Sibley (yeah, the one) recently raised the question visiting birders (particularly from Germany, not so much from the UK – I am told!) have asked themselves for ages: Is the Brown Creeper more than one species?

In addition to differences in vocalizations, he mentions a few field characters that might serve to separate the four different forms that may indeed be four separate species – yes, four. Four as in one less than five but two more than two. Four. And this – his rendering of potential field characters – is where the playful innocence of North American birding is demonstrated in its sweetest and most charming way:

“rump dark chestnut”

“bill shortest of all”

“underparts whitish”

“flanks may be more buffy than…”

Yeah, right.

As if Certhia was just a synonym for Dendroica.

Folks, that’s not going to work – and I am certain Sibley knows it, he’s just trying to be nice to ease the pain, or rather increase it gradually.

If you want a little taste of how different Certhia forms are distinguished, and I mean truly determined at species level by the pros (ha ha), you might want to take a glance at how we here in the Good Old Europe separate Common from Short-toed Treecreeper. And that glance may be short, but be warned: it’ll be fierce nonetheless.

We’ll start with a picture composition of both species side by side (Short-toed on left, Common on right):

Short-toed (left) and Common Treecreeper (right – where else?) – notice fine differences in overall colour that will be described below and notice that I was also very pleased with how well both pictures fitted together.

In an ideal world, you’d be able to identify the Short-toed Treecreeper by its overall more dull and brownish, less pristine and crisp appearance: the lower flanks are duller brown, the supercilium is hardly in contrast to the rest of the bark pattern, and the crown and back appear dull brown. On Common, the white supercilium usually will make you grab your shades in the forest’s shade, the lower flanks are mostly white, and the crown and back show nice white specks.

Easy, right? Just like spring wood-warblers, yes? No big deal, that potential split of the Brown Creeper into four species, or is it?

Answers: No! No! It is!

Why? Well, because these features are all supportive and tentative but far from definite. There is considerable variation within both species and some populations of the one species will look like some populations of the other when compared to other populations of themselves. By which I mean a member of a dull population of Common Treecreeper will appear like a Short-toed Treecreeper amongst members of a more contrasting population of Common.

In short: if you hand in a report of an out-of-range Short-toed to a rarities committee e.g. in the UK using these features, the committee’s members will laugh all the way from their desk to the shredder.

If you really want to know what’s creeping up the trunk in Europe, you’ll need to analyse the exact wing pattern, as shown on the picture below. That, apart from vocalizations (which may overlap, too), is the only way to do it, and I dare say that this kind of stuff will be the only way of definitely discriminating between the different forms of the Brown Creeper.

[Please remember that this post is not meant as an identification article on the two European Treecreepers. It is meant to scare North American birders. Therefore, the following lines on the separation of the two species will be written in a rather rough and general way.]

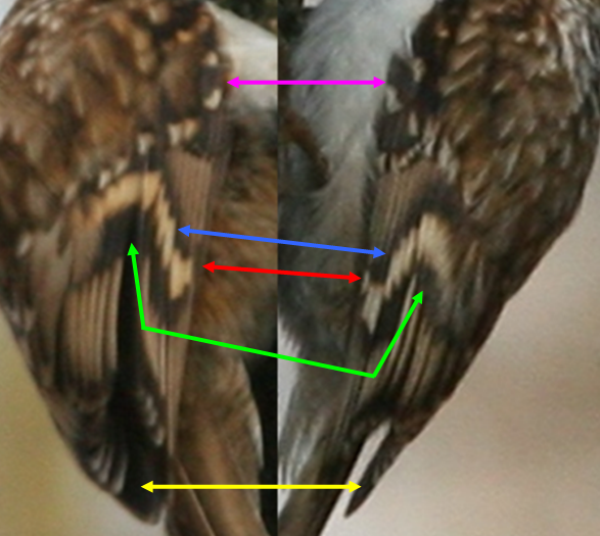

Wing pattern of Short-toed (left) and Common Treecreeper (right), with arrows pointing to the discriminating patterns, details are below – for those who are still with me.

Pink: the pale pattern on the alula is usually more extensive on the outer web on Common than on Short-toed, but there is considerable overlap. On the birds above, it’s not really working.

Blue: this is quite possibly the most important feature and the one most likely to be assessed without a photograph to analyze. The pale bars on primaries 6, 7, and 8 (counted from outside towards the center of the wing) overlap to almost equal extend in Common, forming a “stairway”. In Common, there is considerable overlap between primaries 7 and 8, but almost none between 6 and 7, forming a large right-angled blackish “corner” on the folded wing. Note also that the border of the pale bar towards the tip forms a more prominent saw pattern in Short-toed compared to Common.

Red: A small pale spot is usually present on the fourth primary in Common, but often lacking in Short-toed.

Green: the dark wing bar below the pale wing bar on the secondaries is quite evenly broad in Short-toed, but less well-defined and narrowing towards the primaries in Common.

Yellow: the visible spacing of the primaries 6 to 8 is rather even in Short-toed, but more uneven in Common, with the tip of p7 being very close to p8, and a big step between p6 and p7. This is sadly not visible on the pictures above due to an unfavourable angle on both pictures.

There are more features on the wings, e.g. regarding the exact shape of the pale primary tips and the contrasts between the outer & inner web and the tip of the largest tertial, but I guess the few features above demonstrate what American birders should get emotionally prepared for. This is what the forests will have in store for you once the split has occurred. Therefore, here is a little advice for you:

Go out now and enjoy your forests while you can. And consider collecting stamps or other indoor hobbies. But no matter what you do…

… they are waiting for you!

.

* The German name for the Brown Creeper translates to “Andes Creeper” – don’t ask!

Bwahahaha! Between that and the upcoming crossbill splits American birders will be too scared to even leave their houses!

Jochen, may a swarm of unidentifiable Empidonax flycatchers land in your backyard and mock your inability to figure them out.

Meh, due to geography I still don’t have to think about these 99% of the time.

Jochen, as a metaphysical system this remains intriguing, but come on. We all know you just ran that Treecreeper through a Photoshop filter.

Hello Chaps,

just arrived, hope I haven’t missed anything.

It sounds like the real headache will be for birders in Arizona.

Well, at least we can all assume that David Sibley will get the range maps right. Unlike my edition of the “birds of europe”, where the short-toe treecreeper seemed to be completely extirpated from europe! (talk about a roten trick!)

Great post Jochen. Hope to see you back on our side of the pond soon (Hint, next month would be good timing!).

@all: I was off-line abroad until the beginning of this week, hence my late reply.

@Duncan: Do you think they’ll send us their fancy Swaro equipment then? It would be such a shame if all their scopes would do was collecting dust in their closets.

@Corey: may a Black Kite be sent your way and you’ll mis-identify it as a Turkey Vulture in Queens. Oh wait, that’s already happened!

@Jason: this might just be the beginning. First they sort out the four major forms, and then they dissect each and every form for more potential splits. Start thinking now, about an escape route!

@Carrie: I never thought about treecreepers being an intriguing metaphysical system. I never thought about groups of finches making lace or snakebirds doing a funky dance. And I never thought about potholes – at all. Carrie, you keep changing a lot of things…

@Redgannet: Ha! 🙂 No, no worries, all’s fine as usual. The bird’s gone, the party is over, now go grab yourself a beer, sit down and relax. But not a beer out of the fridge, that might be cold and you won’t like that! 😉 🙂

@John: frankly, I wouldn’t be so sure – seriously. I saw quite a few treecreepers around the Great Lakes and noticed a huge amount of variation. And if you ask me… Okay, don’t ask me.

@Laurent: ah, but you see all has been fine in the German version of the field guide. I wonder why the Germans got it right again about the two ‘creepers while the Brits messed up? 😉

And not this year, Laurent, not this year. But the day, wait, the May will come…