I have been working in the avian world for 25 years, but last summer I was out-birded by a 14-year-old girl.

Actually, I was bested by an entire group of teenagers, all gathered – along with 36 adults – on Hog Island, Audubon’s famous camp off the coast of Maine. Each year Hog Island offers programs, taught by a stellar staff of naturalists and artists, to groups of all kinds (teenagers, adults, families). I was there for Arts and Birding, a five-day adult course in photography, videography, sketching, painting, writing, or any combination thereof … plus lots of birding.

Bird Studies for Teens was running simultaneously, which allowed the adult group to share meals, certain boat trips, and after-dinner speaker presentations with sixteen 14- to 17-year-olds. Hog Island offers programs for all levels of birders, from beginners to experts. Arts and Birding, however, was attended by a sizable section of people who freely admitted to knowing nothing about birds, other than it might be fun to draw or photograph one against a blue Maine sky.

And here was one of the most surprising elements of my week on Hog Island: that so many disparate people – from grey-haired professional nature photographers, to couples who wanted to spend a summer week filling their sketchpads, to singles on a bird-themed adventure, to teenagers with mind-boggling birding skills – were all there trading stories, soaking up inexhaustible pools of information, and having a really grand time.

A Ruby-throated Hummingbird has approximately 900 feathers; a Tundra Swan, 200-300,000.

“We’ll be leading a bird walk tomorrow morning,” announced Bill Wallauer, as just-arrived campers gathered on the dock and the sky turned brilliantly pink. A renowned cinematographer, Bill spent 15 years recording the lives of chimpanzees in Gombe National Park; along the way he met his wife, photographer Kristin Mosher, a photographer who worked for Jane Goodall. And here were Bill and Kristin on Hog Island, both ready to lend their expertise to any campers lugging photographic equipment.

“We’ll gather at the flagpole at 5:45 AM,” said Bill. “The light is fantastic!” Responding to several looks of alarm, he added hastily, “It’s voluntary! You don’t have to come!”

Meals, served at picnic-style tables in the dining hall, were where you found a seat, ate fine, hearty food with your teachers and fellow campers, and received your upcoming schedule. A flatscreen TV mounted on the wall provided a view of the nearby Osprey nest, resting on a platform 20 feet in the air, home to three chicks; a Merlin nest was secluded away from the buildings, their privacy respected by the camper paparazzi (although some patient souls managed to get great photos with their telephoto lenses).

A Magnificent Frigatebird’s feathers weigh more than its skeleton.

On our first morning after breakfast, my group and the teens piled onto a boat and headed out to Eastern Egg Rock, once again the breeding ground for Atlantic Puffins (as well as a host of other seabirds) thanks to biologist Dr. Stephen Kress. Nearly exterminated in Maine by hunters in the 1800‘s, the charismatic, orange-beaked little puffins nested only on one other state island until Dr. Kress painstakingly – and groundbreakingly – lured them back to nest on Eastern Egg Rock in 1977. The process took eight years and has since been duplicated all over the world with a variety of species, explained one of our guides … the genial and informative Dr. Kress himself.

As we coasted through the water, staff member Tom Johnson pointed out basking harbor seals and identified birds for the uninitiated (“Female Lesser Scaup at two o’clock!”) He then led a lively game of name-that-bird charades by flailing his arms in simulations of various wingbeats, timing his flights so as not to fall overboard during oceanic swells. An hour later the teenagers piled into a dingy and headed for the island, which is off-limits to everyone but Audubon personnel and certain groups of campers. I and the rest of the adults – some armed with spotting scopes the size of my torso – watched from the boat as a single line of kids, all stepping precisely in the footprints ahead of them to avoid crushing an egg or a chick, walked along a trail at the edge of the island, furiously mobbed by terns and gulls.

“What was it like?” I asked one of the teens when they rejoined us. The normally chatty and effusive boy answered me with a blinding grin, struck momentarily mute by the memory of swirling birds, tiny chicks, and an island covered with nesting Puffins, Guillemots, Roseate, Common, and Arctic Terns, Laughing Gulls, and Common Eiders.

Most “bird-friendly”-labeled coffee is not bird-friendly at all. Here are some that are: Birds & Beans: Golden Valley; Cafe Ibis.

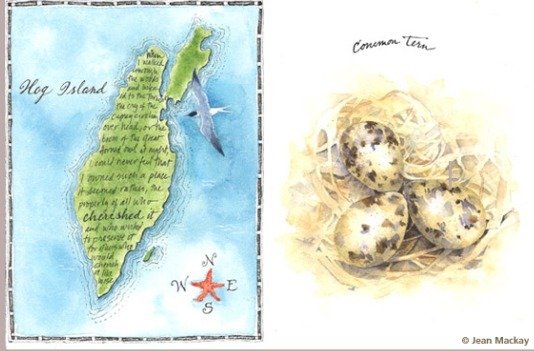

We stopped on a nearby island for lunch, a hike, and an information-packed talk about the area’s geology from staff member Eric Snyder. Harbor Island is an artist’s paradise of ferns and sea caves, of spruce trees trailing Old Man’s Beard and enormous, lichen-covered rocks leading down to the ocean. Artist Jean Mackay hit the trails with a group of sketchpad-toting campers, offering pointers here, suggestions there, revealing her own creations (see above) when asked.

Drawn in ink and finished with delicate watercolor, Jean’s sketchpad was a treasure trove of newts and dragonflies, summer peaches and winter constellations, sturdy barns and old sneakers and blooming lilacs. Curled around her drawings were observations written in graceful, ethereal calligraphy, giving each page a feeling of timelessness and poignancy. Inspired, campers fanned out onto the rocks, pulled out their sketchpads, notebooks, or cameras, and let their creativity flow.

The Hog Island Salon was held each night before dinner, giving campers the opportunity to share their day’s creations. There were photographs, artwork, and descriptive paragraphs enticed from writers by wildlife biologist and writing instructor Nina Stoyan-Rozenzweig; all were on display in the assembly hall, where mutual admiration and camaraderie grew by the day.

Puffins growl like chainsaws, and one in Britain was seen carrying 62 fish in her beak.

One morning I skipped a trip to Damariscottato go bird banding with the teens, who chatted animatedly as we trouped into the woods with mist nets and bags of equipment. Our fearless leader was author, naturalist, and master bander Scott Weidensaul, whose book about migration – Living on the Wind – was a Pulitzer Prize finalist.

“What’s it called when birds return to the same nesting spot?” he asked the group, as we settled in a small clearing and set up the nets.

“Site fidelity,” a 15-year-old girl responded immediately.

As a wildlife rehabilitator, I am used to dealing with the (sometimes) well-meaning but uninformed public, who ask questions like “Do birds have bones?” What followed was the kind of gathering that makes a hardened, weary environmentalist’s heart fill with hope.

“We don’t want to catch any brooding females,” announced Scott, who instead played the war songs of territorial male songbirds on his iPod in order to lure them into the net. The birds were then measured, weighed, fitted with tiny silver bands, and released; with luck some will be temporarily netted again in the future, and their statistics added to the growing database of wild bird survival rates.

The fastest Hog Island capture-time on record is six and a half seconds: from the moment a Golden-crowned Kinglet’s song was played, to the moment an enraged male was caught in the net.

During the banding there was no one-upsmanship, no attempted takeovers by dominant personalities; it was simply a group of kids who love the wild, adding to their already startling range of knowledge by way of a gifted educator who could simultaneously teach, entertain, and enthrall. I watched the expressions of the kids, some of whom had been birding since they were four, some whom had a couple of years under their belt; listened to them compare the songs of Wilson’s and Arctic Warblers, describe efforts to save the Delmava fox squirrel, and state that in certain areas of West Virginia, you can almost see the giardia in a drinking glass with your naked eye.

“In my own defense,” said one boy, ruefully displaying his camera, “I had a choice between spending my money on a kayak or a better camera.”

“Here, try mine,” said another encouragingly. “And that’s not so bad. Seriously, I’ve seen far crappier cameras than yours.”

Blackpoll Warblers binge-eat before they migrate. If fat were gas, they would get about 720,000 miles per gallon.

One afternoon we followed “Seabird Sue” Schubel down to Porthole Beach, where we discovered the seemingly unremarkable stretch of sand was actually an intertidal zone teeming with life, a nursery for larval fish, and a battleground where tiny crabs fought epic wars. It was also an open-air restaurant where periwinkles could be gathered, cooked in a pot by Eric, and eaten on the spot.

“Look!” cried Sue, cradling a handful of seaweed. “A knotted wrack and a bladder wrack have fused together!”

Fueled by Sue’s enthusiasm, our group crowded around excitedly but silently. “It’s just …” one camper finally blurted. “It’s just we’re not sure how to respond emotionally.”

That night the Hog Island Salon overflowed with sketches, descriptions, and close-up photographs of the miniature sea life so often taken for granted, and people began exchanging contact information and reminiscing about the first two days of camp.

There are over a million species of arthropods. They live on land, in the air, freshwater, and the sea, and have been compared to Swiss Army knives for their versatility.

One afternoon when other campers were working on their projects, my new friend Katie and I decided to hike the 5-mile perimeter trail of the island. Solo hikes are permitted during free afternoons as long as the instructors know you’re going; ours happened to arrive the day after an all-night downpour. Katie appeared in waterproof boots and rain pants, carrying 30 pounds of gear.

“Where’s your stuff?” she asked, eyeing my jeans and hiking boots. I reached into my pocket and pulled out my cellphone, a notepad, and a pen. Katie regarded me silently.

Note: after torrential rain, the trails turn into rivers, if not lakes. Insects abound. Bushwacking is required. So is wading.

“I think my boots were just sucked off my feet,” I said at one point. “And by the way, I have no idea where we are.”

“Neither do I,” said Katie. “But there’s the ocean. If we keep our eye on it and don’t stop walking, odds are someday we’ll get back to camp. Here. Drink some water.”

Even partially submerged by rainwater and covered by leaden skies, the island was glorious: spruce and fir forests, moss-covered boulders, fern fields edged with bunchberry and wild yarrow, sphagnum bogs and rocky beaches, all fit for a fairy kingdom and home to Parulas, Winter Wrens, and Black-throated Green Warblers. By the end of the afternoon the clouds had parted and streaks of late June sunlight poured through the trees, illuminating trail markers and inspiring us to greater heights of storytelling, solidarity, and hilarity.

The day before we left was Guillemot Appreciation Day.

Guillemots are striking black and white, red-footed ocean birds who – according to the Audubon crew – have not received the fame they deserve because the puffins are so busy hogging the limelight. Thus on the final day we talked about guillemots and dressed like guillemots (white arm bands, red triangles pinned to our sneakers); three creative campers baked a cake shaped like a guillemot; and after dinner various staff and campers took to the stage, reciting odes to guillemots and singing guillemot folk songs.

“Just remember,” said a gaily-dressed Hog Island volunteer, adjusting her guitar as she leaned toward the microphone. “I’m a biochemist, not a musician.”

The grand finale was the staged version of Guillerella, the cast including a mix of campers, staff, and volunteers. The downtrodden maiden has morphed into a beleaguered seabird; she (played by one of the teen boys) fends off ill-tempered step-guillemots, an evil Greater Black-Backed Gull, and various habitat hazards, finally emerging triumphant not because of a glass slipper placed on her foot by a prince, but because of a silver band placed on her leg by a field biologist (Dr. Kress). The audience, giddy from a week on Hog Island, rose to their feet and cheered.

It’s no wonder some campers return year after year, and some eventually send their kids. The established courses fill up quickly, so Audubon keeps adding new ones and attracting renowned instructors.

This year’s eagerly anticipated pilot programs, Hands-on Bird Science and Breaking into Birding, offer something for everyone, no matter what their level of experience. And this year’s Joy of Birding, led by author and World Series of Birding founder Pete Dunne, will welcome seven-time Grammy Award winner Paul Winter for no-musical-experience-necessary evening programs combining music and the sounds of the natural world.

As it turns out, you can go home again – or at least, back to an idyllic week of summer camp.

Banner artwork by Jean Mackay; all photos by Suzie Gilbert except the Hog Island double rainbow, by Steve Kress.

Great information Suzie! We’re loving the piece over here in the Hog Island Audubon Camp office.

So glad, Eva! I wish I was back there on Hog Island with you, even in January!