Last week many birders were shocked and saddened by the deaths of thousands of Snow Geese who, trapped by adverse weather conditions, landed at the Berkeley Pit in Butte, Montana. While Snow Geese are not exactly endangered – indeed far from it – the existence of a large open body of death-water is a pretty alarming condition to contemplate! You may be curious about what exactly is the deal with that. As an Explainer of Montana, I am here to help.

The history of Butte is a history of resource extraction. The notorious Copper Kings were headquartered there – a collection of robber barons whose battles to control and profit from Montana’s minerals left marks not only on the stones of the state, but on its psyche. Through a series of legal and financial battles their holdings eventually merged into a monopoly, the Anaconda Copper Mining Company, that dominated the employment landscape of the city and owned newspapers and politicians as well as tunnels and smelters. In 1917 I.W.W. union organizer Frank Little was lynched from a railway trestle outside Butte, and no one was ever arrested or charged for the crime. Dashell Hammett, then employed as a Pinkerton agent, later alleged that he’d been offered five thousand dollars to murder Little in the course of his work. Whether this tale is true or false, there’s no doubt that during Hammett’s second career as a writer he penned one of the most vivid fictionalized accounts of Butte’s labor troubles. You may know it under the title Red Harvest, but when it was first serialized in the magazine Black Mask it was called “The Cleansing of Poisonville”.

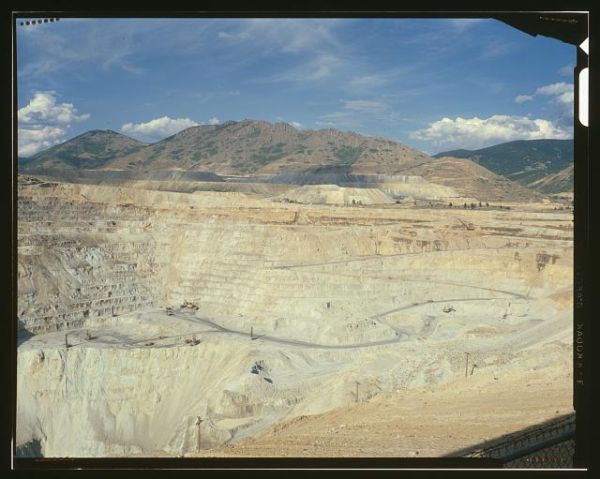

Poisonville was an apt nickname for Butte at that time – mining scattered sulfur, mercury, arsenic, and a wide variety of other entertaining substances about the landscape. The air, thin at the best of times, became smokey and oppressive and the trout waters of the Clark Fork (famous as the river from A River Runs Through It) were slowly stifled. Then, in 1955, the Anaconda Company began excavating an open-pit mine, a technique that was less costly and dangerous but even more destructive than traditional mining. This was the origin of the Berkeley pit, the operation of which devoured the communities of East Butte, Meaderville, and McQueen. Copper, silver, and gold were all extracted from the pit for almost thirty years, resulting in a hole 7,000 feet long, 5,600 feet wide and 1,600 feet deep. When it closed in 1982 the hole began to fill with groundwater. When water met oxygen and ore the result was an acidic (2.5 pH level) stew laden with copper, arsenic, cadmium, and zinc. The conditions in this water are so extreme that new species of bacteria and fungus have evolved just to deal with them.

Today the Berkeley Pit is a Superfund site and also, perversely, a tourist attraction with a gift shop. It does not only pose a risk to waterfowl – although this year’s incident is not the first time flocks of Snow Geese have met their end there. As water continues to rise in the pit, there is a risk that it could backflow into the local groundwater and contaminate the headwaters of the Clark Fork, which has been the subject of intensive remediation efforts over the years, once again.

Feature photo: The Berkeley Pit in operation, 1980. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Thanks for posting about this tragedy, Carrie, and for giving us the important historical context. Sad to realize that the next 4 years may only bring birds nesting or traveling through the U.S. more of the same.

To someone who works in the mining industry, this whole thing is highly shocking. There is a lot of complaining that Permit procedures here in Germany may take 10 years in critical cases, but maybe that’s the reason we don’t have something even remotely resembling the Berkeley pit.