One good thing about birding during a pandemic–the forced restrictions on place and time translate into more time to observe what birds do. And so, I’ve spent the past few weeks observing Black Skimmers doing aerial maneuvers as they skirmish with one another for no discernible reason; young Ospreys building a lopsided nest atop a high school athletic field pole, too sparse for actual nesting but hopefully good practice for next summer; Piping Plover chicks picking grubs out of the mud flat till mama sounds a high-pitched warning note, the signal to run back and nestle safely beneath her body, all legs hidden. Bird behavior–endlessly fascinating, but so much still hidden and unknown. It was a pleasure to make these observations at the same time I was reading The Bird Way: A New Look at How Birds Talk, Work, Play, Parent, and Think, Jennifer Ackerman’s new book about the diversity and complexity of bird behavior.

A logical and outstanding successor to The Genius of Birds (2016), Ackerman’s award-winning book about bird cognition, The Bird Way explores the diversity of bird behavior, the norm and the extremes, with an emphasis on cutting-edge research and findings that explode assumptions. The book is divided into the five sections–talk, work, play, love, parent–and within those sections into 14 chapters that focus on a singular aspect of that behavior–alarm calls, mimicry, using smell, fire spreading, following army ants, Raven play, Kea play, diversity of sexual practices, crazy and exotic ways of wooing the female, diversity of parenting behavior (including Brush Turkeys, who bury their eggs in a huge mound of leaf litter where the hatched chicks must fight their way out), brood parasitism (which demands more skills than you may think), and cooperative parenting. There is a lot of extreme behavior here (and a lot of that behavior takes place in Australia), but this is not simply a collection of the world’s most fantastic bird tales.

As Ackerman explains in her Introduction, studying extreme behavior brings new insight into what we think we know. For one thing, we become more aware of cultural biases in our science (new findings on warbling female birds, for example, reveal both gender and geographic biases). We can use new technologies to push aside ingrained assumptions and fill in the details of vague observations. Extreme behaviors also push scientists to look at birds in new ways. The complexity of the ways in which they use their voices, find food sources, and attract mates belies the often anthropomorphic view of birds as sweet, pure beings with tiny brains (it turns out that these brains are full of neurons). Simple no longer, the research detailed in this book reveals “remarkable strategies and intelligence underlying these activities, abilities we once considered uniquely our own, or at least the sole domain of a few clever mammals–deception, manipulation, cheating, kidnapping, and infanticide, but also ingenious communication between species, cooperation, collaboration, altruism, culture, and play” (p. 3). It’s fascinating stuff.

Most of the chapters in The Bird Way focus on one or two scientists who has done extensive research on ‘outlier behavior.’ Ackerman visited some of their field sites and shares her experiences–walking with Ana Dalziell in the Blue Mountains of East Australia to learn about Supreme Lyrebirds, mimics supreme; visiting the home of Swedish zoologist Mathias Osvath to meet six Ravens housed in his home aviary and watch them at play; walking with Will Feeny and his research team from the Environmental Futures Research Institute in a scrubland north of Brisbane, tracking fairy-wren nests that have been parasitized by cuckoos. Other research stories are based on interviews, descriptions of the scientists’ work punctuated by stories of personal challenges–Sean O’Donnell’s 11 years in Costa Rica researching army ants and antbirds also involved an almost fatal bite by a bushmaster, a venomous snake; Christina Riehl and her team must deal with crocodile-infested waters when researching cooperative parenting amongst Greater Anis in Panama (the Anis nest along the shoreline and the researchers work from small boats). Yet, the research projects are never the whole story. Ackerman surrounds each individual story with background facts and studies on other birds who mimic, play, parasitize nests, engage in complex cognitive routines, parent in unusual ways–presenting a complex mosaic of avian behaviors amongst bird families and the scientific histories of trying to understand them.

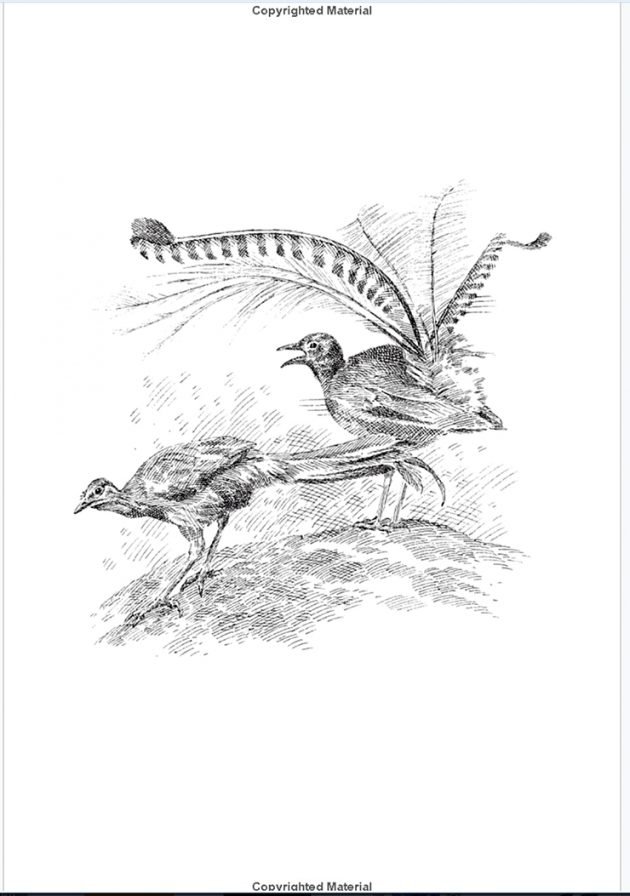

Superb Lyrebird by John Burgoyne ©2020

Each chapter is introduced with a drawing by illustrator John Burgoyne that shows with flair and a sense of humor one of the behaviors highlighted in the chapter (here, the courtship singing and dancing ritual of the Superb Lyrebird). Burgoyne also illustrated The Genius of Birds, but for some reason is only credited in small print on the copyright page. If you want more of a visual counterpart, you can read The Bird Way next to your computer or with smartphone in hand. This way, you can easily look up images and videos of the many fantastic birds described. This is a bit of a rabbit hole, however, and you may find yourself, as I did, spending the day watching videos of Superb Lyrebirds singing and Kea Parrots making snowballs.

Many readers will be perfectly happy simply reading Ackerman’s descriptive prose, which is elegantly visual in its descriptions of birds and place, lucidly engaging when talking about research methodology, and surprisingly humorous when discussing larger implications of the research she details. An accomplished popular science writer, Ackerman started out as a writer and researcher for National Geographic‘s book division and has since written articles and books on such diverse scientific subjects as heredity, the common cold, dragonflies, and wildlife in Japan. Her bird books are Birds by the Shore (previously Notes from the Shore, 1995 and re-issued 2019) and the award-winning The Genius of Birds (2016), which focused on studies of bird cognition. Ackerman has done a lot of interviews about The Bird Way, and as usual I highly recommend listening to here on the ABA Podcast.

I do have some minor criticisms, and these are what you may call procedural. Like most mainstream books, The Bird Way does not capitalize bird names (unless the name includes a person’s name) and this can make for confusing reading. I was particularly thrown by mentions of the Happy Wren, a Mexican wren that engages in complex duetting. For a few minutes, I really did think Ackerman was talking about wrens that were joyous. Although there is no bibliography, there is a “Further Reading” section which lists relevant research studies for each chapter. The librarian in me takes issue with the formatting of these citations, which start with the author’s first name initials followed by surname, yet are alphabetized by surname. It is really difficult reading through these to find a specific author! Please consider the classic practice of surname first. Finally, the index lists birds by their full common name–“happy wren” is under H, “spotted antbird” is under S, etc. For those of us who can’t remember the exact names of the Antbirds or Wrens cited in this book, the index is rendered useless. I am happy, however, that there is a list of readings and that there is an index. Many popular science books have neither.

In the year of the book of bird behavior (this is the second title I’ve reviewed so far and there are several others coming down the bird publishing turnpike), The Bird Way: A New Look at How Birds Talk, Work, Play, Parent, and Think stands out for its daring take on this subject and for its writing excellence. I’ve read few popular science books that are able to explain scientific thought with such engaging, non-scientific language comprehensiveness. And, I find myself thinking about its ideas when doing my own bird behavior observations. There is no one way to be a bird, according to Jennifer Ackerman. Maybe that means there is no one way of being a birder.

Leave a Comment