I needed a book showing a Linnet. There is a Linnet at Kissena Corridor Park in Queens, and though I bird this park regularly, the Linnet, a bird regularly found in Europe, Asia, and North Africa and also named in a sweet song by Stephen Sondheim (Green Finch and Linnet Bird from Sweeny Todd) has eluded me. Maybe I had seen the bird and I didn’t know it? The description sounded a lot like a House Finch. I needed more background than the photos some of my friends managed to obtain. A bird guide was in order. Fortunately, I had The Crossley ID Guide: Britain & Ireland by Richard Crossley and Dominic Couzens on my desk. The large plate showed six images of Linnet perched, nine images of the bird in flight, and detailed description of the bird’s appearance and behavior. I studied it. I knew I would not be seeing the bird in its rosy-breasted breeding plumage, but somehow seeing the bird in all its forms helped crystallize its appearance in my head. Sadly, I still did not see the bird. But, I now knew enough to know that I was looking at House Finches, not Linnets. And, I had a good example of the usefulness of the Crossley method with which to begin this review.

Most U.S. birders are familiar with the Crossley ID Guide series. Conceived and authored by Richard Crossley, birder, traveler, and photographer, The Crossley ID Guide: Britain & Ireland is the third book of the series. The principles behind the Crossley ID Guides are simple:

(1) We learn more efficiently how to identify birds when we view them in their habitat;

(2) We are better able to identify birds when we view their images at varying distances and angles and positions, including flight shots, this helps us learn which features change and which remain constant;

(3) We obtain a better understanding of molt when we view the bird in its various plumages in one single image;

(4) We have technologies we have never had before. Digital technology allows us to present high-quality photographic images together, in one plate, presenting valuable information on birds’ appearance, habitat, and behavior.

The first book in the series, The Crossley ID Guide: Eastern Birds, exploded onto the birding scene in 2011. Birders loved it or hated it or were just confused. The book sparked constructive conversations about what is a field guide and the efficacy of drawings versus photographs in a bird guide and just how far does one tweak a wildlife photograph for publication. Crossley has wisely positioned his series as an educational resource, to be used as much at home as in the field. Using Crossley ID Guides, he says, is more than the simple match-up a beginning birder performs with the traditional field guide. He encourages birders to use the book interactively, studying the plates, observing details in close and far images, working on aging and “sexing” the images. The images and text provide a context for understanding a bird’s appearance and habitat; the beginning and intermediate birder can then observe the bird in the field, and build on this knowledge base.

I find the Crossley Guides, Eastern Birds and Raptors (fall 2013), very useful when I’m looking for new or unfamiliar birds (Linnet!), or birds that look very different in their breeding and non-breeding plumages (Shorebirds! Gulls! Ducks!), or birds usually seen in flight (Raptors!). I often use the book in conjunction with other bird field and identification guides. The Crossley books serve as a useful first step in trying to narrow down possibilities. It is also an excellent last step once the bird has been identified; I consult it to get a mental picture of the “whole bird.” This is how I learn, by doing and reading. We all have different ways of learning, and I’m really curious as to how other birders use these books.

The Crossley ID Guide: Britain & Ireland, covers 314 birds (I counted) that reside in or migrate regularly through England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland. It also offers images of at least 21 more birds that are exotics and possible vagrants (I counted, but may have missed some). The British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) has documented 596 bird species in the wild as at 1 January 2013; 265 are listed as Accidental, 59 as Scarce Visitor, and 2 as Extinct. Which, when you do the math, means that the guide covers all resident and migrant Breeders, birds that “Occur Year Round”, regular migrants, and then some. The text (new text, as we will see) is by Dominec Couzens, British birder and author. Most of the roughly 5,000 photographs (birds and background) are by Crossley, with 34 additional photographers noted in the Acknowledgements.

The 14-page Introduction provides the rationales for the Crossley system, guidelines for the most effective use of the book, explanation of the terminology used for plumage and molt (the Life-Year System), and Bird Topography diagrams—nine images illustrating different bird parts. This is seven more than the number of images usually employed to illustrate bird anatomy (though one less than the number of diagrams in the Eastern Birds guide, which also includes a hummingbird). Different types of birds (songbirds, raptors, ducks, gulls and waders) are diagramed, resulting in a nicely detailed topography section that is as much glossary as diagrammatic anatomy.

Species Accounts are organized into seven chapters based on two major habitats:

– Waterbirds—Swimming Waterbirds, Flying Waterbirds, Walking Waterbirds.

– Landbirds– Upland Gamebirds, Raptors, Miscellaneous Larger and Aerial Landbirds, and Songbirds.

Non-taxonomic organization is becoming more and more common in bird guides. It makes the book’s arrangement friendlier to beginning birders, and helps keep birding guides current in an age in which scientific names and order are juggled yearly. With only 314 species, the arrangement here makes sense until you come to that miscellaneous chapter, which includes pigeons and doves, woodpeckers, jays, crows, swallows, and hoopoe. A miscellaneous pot indeed!

Chapters start with two pages of text summarizing the similarities and differences of the species covered by that chapter, with an emphasis on molt patterns and challenges to aging and sexing certain species. For some reason, there is no introduction to the Gamebirds section, not even a page dividing that chapter from the preceding Walking Waterbirds. This would have been useful, since the introductions serve an organizational purpose as well as an informational one, enabling browsers like me to differentiate between each section.

A couple of additional words about organization: In addition to the Table of Contents and the Index, which lists pages by common name and scientific name, the book features a visual table of contents. A feature of all the Crossley ID Guides, this section illustrates each species photographically, in proportional size and in order of appearance; the code name (in this case, the 5-letter BTO code) and page number are listed underneath. This is a good starting point for birders, especially beginning birders, seeking to identify unfamiliar birds. The Introduction says there should be another visual index of representative species from each family on the inside front cover (similar to the Eastern Birds guide), but the inside front cover of my edition is blank. It’s not clear if this is an oversight or a faulty edition.

Each species account consists of the photographic plate, common name, scientific name, and 5-letter and 2-letter codes, used by the BTO and banders (ringers in Britain). The bird’s average length is shown next to the codes. Abundance information–number of birds in the UK–is taken from the paper “Population estimates of birds in Great Britain and the United Kingdom” by A. Musgrove et al., British Birds 106, February 2013, and is listed under the bird’s common name or, in the case of smaller entries, after bird length. (The Introduction cites a separate source for abundance numbers in Ireland, but I didn’t see any reference to it in the species accounts.) It took me a while to figure out the notations for the abundance numbers, and finally found them on the inside back cover, which also explains map colors and the photographic plate notations on age and sex.

Maps show “regular breeding range,” “regular year-round range,” and “regular winter range.” There are no range maps for a number of species. I can understand the absence of maps for species like Spoonbill (2 pairs in summer, 20 pairs in winter) or rarities like Alpine Swift, but I don’t understand why they are not included for birds like Jack Snipe (1110,00 pairs in winter) or Hawfinch, a species that has seen a steep decline in Great Britain in the past 25 years but which is still a resident breeder.

The text itself describes habitat, significant behavior traits, and identification notes (size, shape, notable field marks, similar species, plumage characteristics for age and sex). Song and calls are described for species most apt to vocalize, often very charmingly. Crested Tit’s trill, for example, “that has an unmistakable bubbling quality interspersed with sharp, high-pitched seep notes.” Couzens is a talented writer, but the format and lack of space give him little opportunity to paint pictures of his birds beyond these song descriptions. He does occasionally manage to squeeze in some lines hinting at a quiet sense of humor. Common Redshank is “extremely nervous and noisy; being near nesting pairs gives you a headache.” Pheasant has been here “for 1000 years, but still looks exotic for British landscape.” Flocks of Fieldfare “(below) move like army troops over wide open fields.”

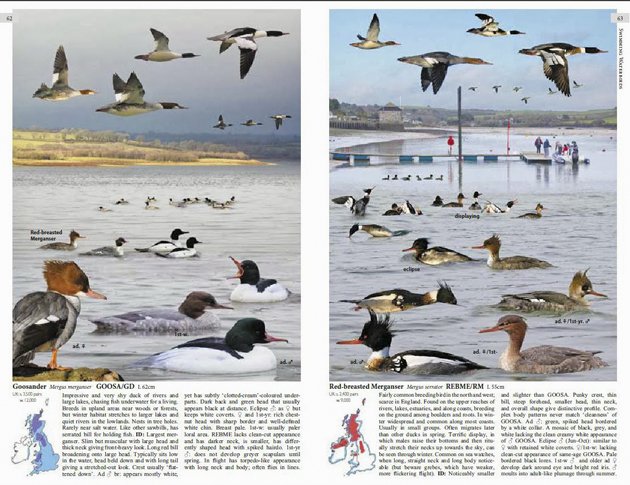

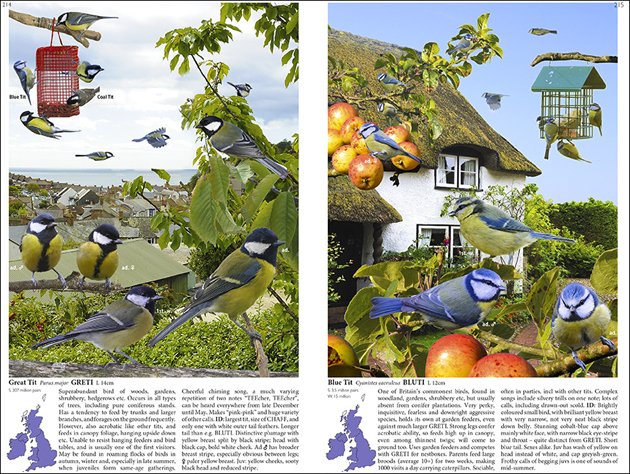

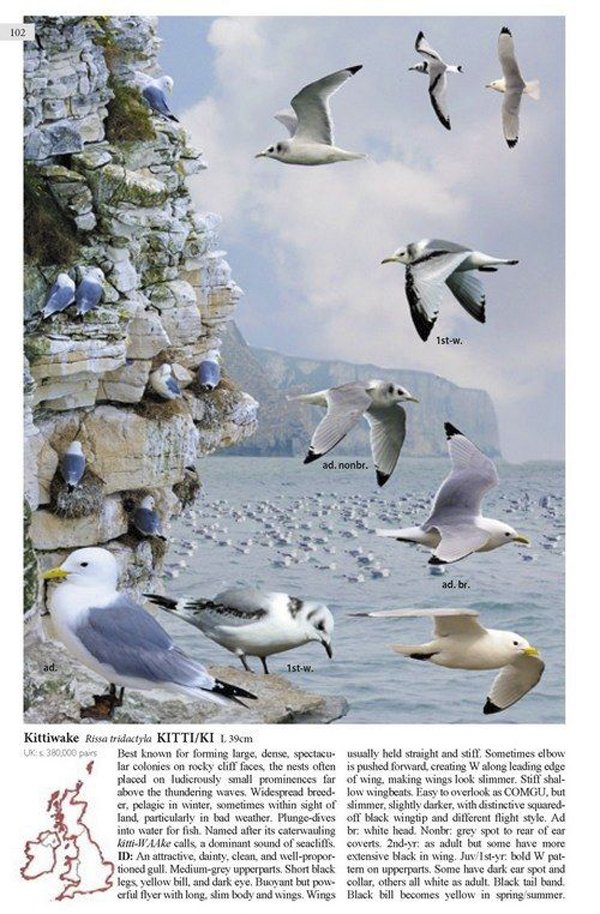

The photographic plates are, of course, the central attraction in the Crossley ID Guides. Newcomers to the series will be astounded by the plates, which combine images of the bird in different plumages, sexes, and ages, positioned against a background reflective of its most common habitat. Many of the images are distant ones, the idea being that this is how we most often see the bird–so far away that the only distinct image we retain is the silhouette. The plates label some, but not all, of the images for age and gender. (The Linnet plate above doesn’t include the labels shown in the book.) Those of us who think we’ve gotten used to these images, should look again. It seems to me that Crossley has been pushing the envelope, adding as many images as he can where he can (there must be over 70 Razorbills), and even adding other species in the background (those have to be Wigeons in the background of the Pochard plate!).

The plates are easiest to use when the bird images are positioned against the sea or the air, a clean background, like the above Kittiwake plate. This is the case for most of the Waterbird and Raptor pages. Viewing images becomes more difficult with the busy backgrounds of the Songbirds, suburban yards filled with shrubbery or fields of tall grass or rocky slopes where the stones exactly match the color of the bird. A little help, maybe exaggerating the color of the rocks for greater contrast or eliminating a shrub or two, would have been appreciated. I miss the vast landscapes of the plates from the Raptors guide, which often presented spacious, two-page layouts.

These are nitty-picky complaints, and they should not detract from the fact that most of these plates are simply beautiful, produced with care for accurate reproduction of color and tone. And informative, bursting with details of shape and structure and molt. My favorite plate has to be the one in the layout above, showing the Great Tit. It reminds me of the first time I saw the bird in Tours, France in 2012. I passed an alley and out of the corner of my eye saw a small ball of color, a bird, perched on a small tree. The Great Tit faced me in all its round adorableness and bright colors, a joyous surprise on a gray morning. Which I imagine is also a function of Crossley’s memorable images, to remind us of birds’ ability to surprise and inspire.

One question that did occur to me was whether there is any overlap between the species accounts for birds found both in eastern North America and in Britain and Ireland. The answer, based on a comparison of the accounts for Common Merganser/Goosander and Red-breasted Merganser, is yes. But, only to the extent that the information is applicable to species on both sides of the Atlantic. The text on physical appearance is almost exactly the same, but the text on habitat and abundance is different. Goosander is an “impressive and very shy duck of rivers and large lakes, chasing fish underwater for a living,” while Common Merganser is “widespread and fairly common on larger lakes and rivers in hilly areas, and other areas of open water.”

Interestingly, the Goosander plate is not the same as the Common Merganser plate; I could only spy three images of the duck that were in both plates. The Red-breasted Merganser Britain plate, on the other hand, utilizes the same images, only in different places within the borders of the plate and against a different background. In Britain, the mergansers are swimming in a lake being used by boaters; in the United States, they are swimming in a marshy area, Osprey nest and water tower in the background. A quick perusal of other common birds shows similar treatments, with many of the same bird images being used in different sizes and against different, appropriate-to-the-country backgrounds.

The Crossley ID Guide: Britain & Ireland is a noteworthy, excellent addition to the European bird guide lists. There are several inconsistencies in organization; these are relatively minor and can hopefully be corrected in future editions. The guide appears to be unique in its geographic coverage; the closest current field guide I could find is Birds of Europe, 2nd edition by Lars Svensson, et al., commonly called the Collins Guide, an excellent field guide in the traditional artwork format. It really does feel like apples and oranges, comparing the two titles. The large Crossley photographs seem lush, almost decadent, next to the tiny, detailed drawings crammed into the pages of the Collins guide. And, though the text covers identical material, the Crossley text is larger in size, making it easier to read. It is also larger in size than the Collins guide, but not by much (the flexible cover makes the difference seem greater); the weight is the same.

If I am fortunate enough to go on a birding trip to Britain and Ireland in the near future, the Crossley guide would be the book in my suitcase. And, if I lived and birded in Britain and Ireland, I would seriously consider purchasing this book for my birding library. Although the book’s publicity material promotes this as a book for beginning and intermediate birders, I think it has much to offer the experienced birder as well. Don’t forget, Richard Crossley was born and raised in Yorkshire, England! I like to think that this book is his gift to the country of his birth. And, I am looking forward to reading the next two titles in the series–The Crossley ID Guides to Waterfowl and to Western Birds.

————————-

The Crossley ID Guide: Britain & Ireland

by Richard Crossley & Dominic Couzens

Crossley Books/Princeton University Press, 2013

flexibound, 304 pp. + color plates. 250 maps. $27.95, £16.95 ISBN: 9780691151946

Leave a Comment