There is no mistaking a Crossley ID Guide. Larger, denser with avian information than your typical field guide, a Crossley Guide bursts with bird images, photographic plates that verge on the surreal of birds in all plumages and poses against real-life habitats, informing, sometimes overwhelming us with visual and, if you can take your eyes off the images, textual information. The Crossley ID Guide: Waterfowl, by Richard Crossley, Paul Baicich, and Jessie Barry is the fourth book in the Crossley ID Guide series, and I think it is the best one yet. It also contains a unique feature that may not be accepted by some birders. But, more on that later.

The Crossley ID Guide: Waterfowl covers every residential, migrating, vagrant, exotic, and introduced swan, goose, dabbling and diving duck in North America (Canada and the United States): 62 Species Accounts on four swan species and one vagrant subspecies; 15 goose species; 46 duck species; plus accounts for hybrid geese, ducks and exotics. The organization is the same as The Crossley Guide: Raptors (PUP, 2013): photographic plates and brief text in the first half and extensive “Written Accounts” in the second half. This is how, I think, the “Crossley technique” works best—coverage of specific bird families that pose identification challenges to birders at all levels of skill. And, whereas the raptor guide was an entry in a field overwhelming with guides and expert advice, waterfowl is a wide-open field, practically begging for a comprehensive identification resource.

Introduction: The guide opens with a lengthy Introduction that lays out the rationale for utilizing the “Crossley approach.” These are, briefly: Photographs are superior to artwork because art lacks the details of photographic images; people learn better from visual information; people learn more effectively from realistic bird images utilizing typical habitat backgrounds than from isolated images; acquiring bird identification skills is an ongoing educational process; the educational process should be interactive. Much of this is arguable, particularly the first three principles. But, there is no doubt that Crossley has utilized these ideas to create a type of identification guide that incorporates elements of innovation, challenge, fun, and continued learning.

The Introduction also covers Crossley’s Six Keys to Identification of waterfowl (size, shape, behavior, color pattern, habitat, probability of encountering bird at location and time of year, and sounds); Waterfowl Topography, a highly detailed photographic guide to the parts of a bird and its plumage; Reality Viewing, a guide to interpreting the multi-bird images that are the heart of the book; Plumages and Molts; and The Life of Waterfowl.

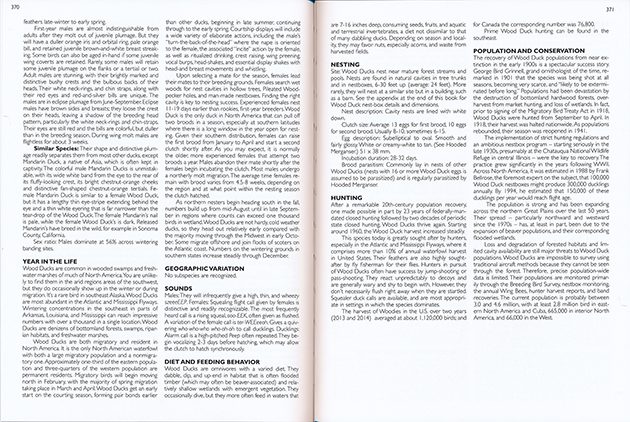

The material on plumages and molts is particularly intimidating and may seem overwhelming to the beginning birder. Crossley recognizes the challenges of this topic, writing, “If you have had difficulty following these issues of aging, sexing, and molt in the last few pages, don’t despair.” However, his solution, to continue onto the highly detailed, heavily illustrated section on “Aging and Sexing Waterfowl,” is not easy to follow. Here’s a sample of how that section reads: “Ducks have 14-18 feathers (rectrices). Juvenile retrices are narrower, more pointed at the tip, and often have a ‘V’-shaped notch cut out at the tip. These feathers are replaced quickly in a few species, not for a year in others; many have a combination of old and new.” It is a relief to eventually reach the chapter on The Life of Waterfowl, written in a much more conversational style and unashamedly fascinated with waterfowl’s unique breeding behaviors.

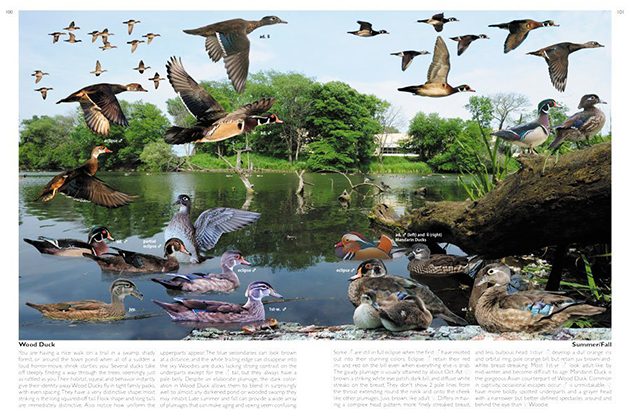

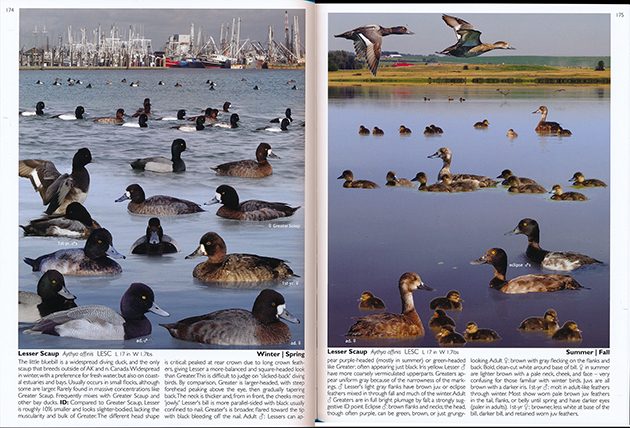

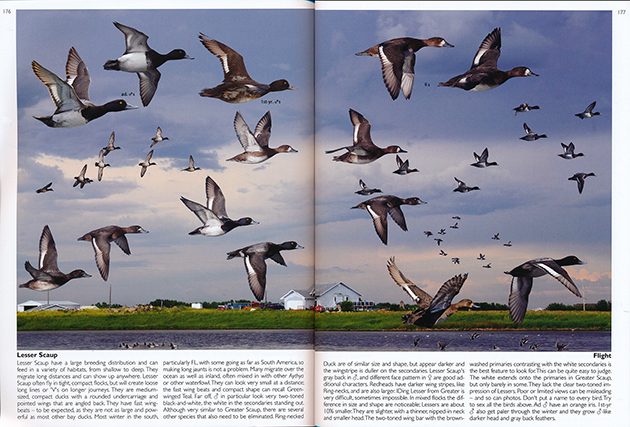

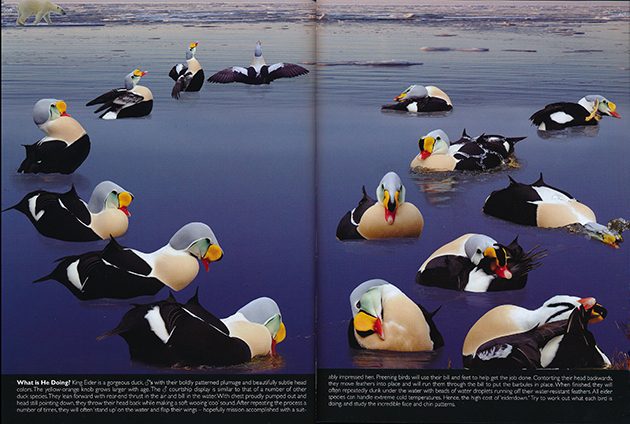

Species Accounts–Plates: Three plates are presented for most species: Winter/Spring, Summer/Fall, and Flying (usually a 2-page plate whose length accentuates the beauty of waterfowl in flight). The first plate, Winter/Spring, gives common and scientific names, 4-letter banding code, and brief size dimensions (length and weight). Plates are accompanied on the page by 9-lines of double-columned text giving a compact description of distribution, habitat, flocking tendencies, significant identification features, and how to differentiate from similar species. Images proceed from close-up full-body to mid-distant to far-distant, all in focus, and present the swan, goose, or duck from the side, full-face, and in typical behavioral poses–preening, head tucked, head in the water, in the field bending down to feed (geese), and, in the flight plates, wings up, wings down, landing, in flock formation.

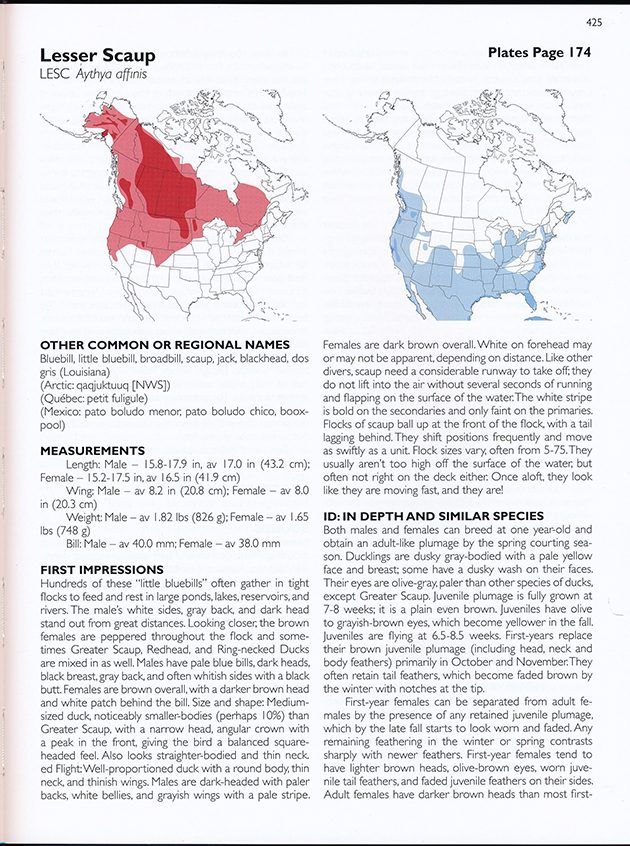

In the Winter/Spring plate here for Lesser Scaup we see the diving duck in 1st year and adult plumage with images labeled for age and gender (not all, just enough to help us identify all the birds in the plate). The Summer/Fall plate shows the ducks in eclipse plumage, with a couple of images labeled for gender, and ducklings with parents. Because, life for waterfowl begins in the summer. (Crossley uses the ‘Life-year’ terminology system, so you won’t find terms like ‘basic’ and ‘alternate’ plumage; lots more on different terminology systems in the Introduction.)

And, if you look closely at the Lesser Scaup Winter/Spring plate above, you’ll see a Greater Scaup. Which is why I chose this particular duck as my example. In five weeks I’ll be doing the Queens County (N.Y.) Christmas Bird Count and I’ll be counting Scaup in Flushing Marina. Lots of Scaup. Mostly Lesser Scaup, but sometimes we find a couple of Greater Scaup. Or, is it the other way around? No, I checked my eBird lists, it’s mostly Lesser Scaup. It is very important to know the differences between these two Aythya species, and to be able to identify the few Greater Scaup because every so often, like last year, other teams do not find Greater Scaup in the expected places (mostly Little Neck Bay), and we need sightings of that bird for the count!

I’ve already started studying. The text on the seasonal pages focuses quite a bit on the differences between the two species–Lesser is about 10% smaller, less bulky overall, has a peaked-at-rear-crown head shape (which I knew, but I didn’t know that this is because of its long crown feathers). There are also differences in bill shape and nail, appearance of upperparts and flanks. And, another thing I didn’t know, in flight Lesser Teal must be differentiated from Ring-necked Ducks and, due to flight style, Green-winged Teal.

The written Species Account for Lesser Scaup elaborates on this “classic identification conundrum,” cautioning that it is most difficult in summer, when head feathers are worn. (So happy I’m doing this in winter!) “When you see a Greater, you know it. It’s large bill and big, rounded head gives it away.” Well, I obviously need a lot of practice, especially learning, on further reading, that “an adult male Lesser will have a very similar wing pattern to a first-year Greater…” (p. 426).

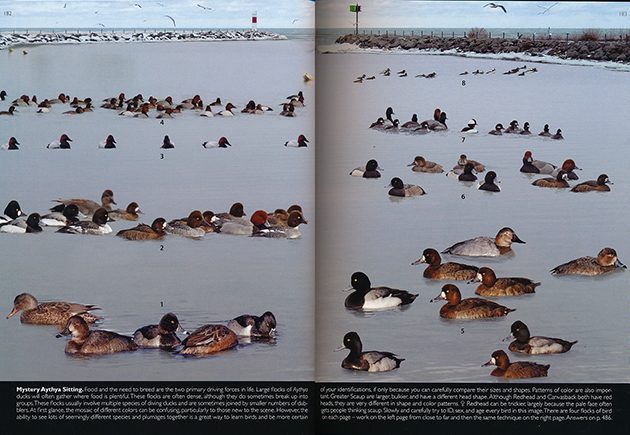

To help us practice, Waterfowl presents mystery plates. There are two for Aythya species: “Mystery Aythya Sitting” and “Mystery Aythya Flight.” Both are two-page spreads presenting Greater and Lesser Scaup, Canvasbacks, Redheads, and Ring-necked Ducks in their black-and-white and sometimes reddish and grayish glory, sitting in a bay surrounded by snow-covered jetties and flying over open water in a wintery landscape. Some Bufflehead, Gadwall, Goldeneye, and American Wigeon images are thrown in, enhancing the realism of the scenes. Tufted Duck and Common Pochard, Aythya rarities, are not included in these mystery duck quizzes, though each species does have its own 1-page photographic treatment.

Mystery Images, or Bird Quizzes: There are, by my count, 24 Mystery Images, as they are called (more if you include the other photographs which pose identification questions). Answers are given at the back of the book, thank goodness. The plates become more challenging at the end of the Visual Species Accounts section, where we’re asked to identify diverse waterfowl in a series of plates that too-accurately reflect real-life situations–distant ducks on a mountain pond, rust-stained birds, freshwater ducks flying overhead with white bellies highlighted by the sun, a lovely image of squadrons of seven duck species flying right with wings outspread, and, my favorite, a mass of duck butts flying away in Buffalo, N.Y. And, more.

Mystery images were one of the innovations of The Shorebird Guide (2006, co-authored by Crossley with Michael O’Brien and Kevin T. Karlson) and they have been incorporated by a number of bird identification guides since. But, none take them to the challenging heights of the guides in the Crossley series.

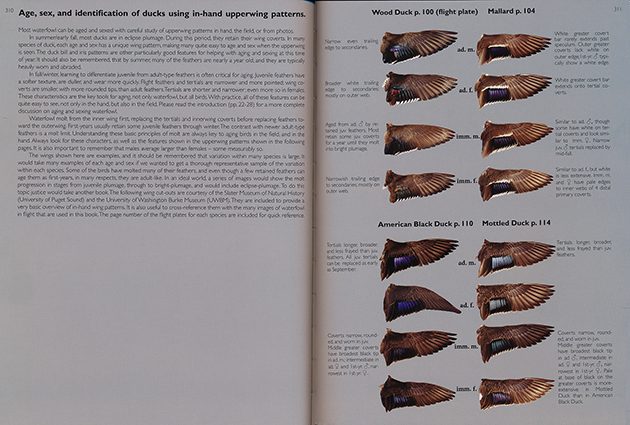

Also Notable–Wings: If you’ve worked on identifying ducks, then you know the importance of wing pattern. The 10-page section aptly named “Age, sex, and identification of ducks using in-hand upperwing patterns” is a guide to just that, utilizing images from two Washington State museum collections. A mid-book extension of the introductory section on Aging and Sexing Waterfowl, this is a unique tool that advanced birders will love. I only wish that it did not use such a dark background. The brownish-gray color of the page affects perception of the wing color patterns, all of which involve shades of brown.

And Hybrids: Waterfowl tend to hybridize to a greater degree than most other bird families, and the guide does an excellent job of covering hybrids. There are plates on Hybrid Geese, Mallard x American Duck Hybrid, Hybrid Dabblers, and Hybrid Divers, identifying combinations and discussing in the text why geese and ducks hybridize (basically, because of incredibly strong urges to breed) and hints for figuring out possible parents. Some of these hybrids are well known (Gadwall x Mallard even has a name, Brewer’s Duck), some are striking but puzzling (Common Goldeneye x Hooded Merganser), some are borderline ugly (Gadwall x Northern Shoveler).

Written Species Accounts: Written Species Accounts take up about one-third of the guide and are presented as “supplemental” to the Visual Species Accounts. Written by co-authors Paul Baicich and Jessie Barry, these mini-encyclopedic articles expand on text in the photographic section, particularly on differentiation from similar species; add additional information on subspecies, diet and feeding behavior, nesting, migration and habitat through the year, hunting, population and conservation; they also include distribution maps (with the exception of most rarities).

Those birders fascinated by subspecies will be glad to see individual distribution maps for subspecies of Canada Goose and Cackling Goose. These birds are also treated extensively in the Visual Species Accounts, with separate plates for Canada Goose–East (Giant, Interior, Atlantic), Canada Goose–West (Moffit’s, Dusky, Vancouver, Anchorage Lesser), Richardson’s Cackling Goose, and Cackler, Aleutian, and Taverner’s Cackling Goose, plus a mystery bird spread on The Anchorage Conundrum.

My favorite part of these species accounts is the section on “Other Common or Regional Names,” which includes historic appellations as well as names of the bird in the Arctic, Quebec, and Mexico. So, I knew that American Wigeon is historically called ‘baldpate,’ but I didn’t know that it has also been called wige, stealer duck, gray duck, and pepper-head. And, that it is Qatkegglig in the Yukon-Kuskokwin Delta, Uuwiuhiq in Norton Sound, and Ugiihiq in the Northwest Arctic; Canard d’Amérique in Quebec (well, that’s obvious); and Pato Calvo, Pato Chalcuán, Pato Panadero, and Pato Poolnuxi in Mexico.

Wood Duck, Written Species Account, pages two and three

Hunting: You may have noticed that the Written Species Accounts include a section on hunting. Yes. Hunting. Varying in length from a brief paragraph to almost a whole column, the hunting text notes historic facts associated with hunting the specific bird, geographic areas where it is hunted, harvest numbers, whether a permit is needed, bag limits, other applicable regulations, and the bird’s behavior around hunters–how open they are to a human presence (most are “wary”) and how the bird reacts to decoys and whistles.

I was really taken aback when I saw this. I am a city girl and until I became a birder my contact with hunting was limited to occasionally seeing dead deer on the tops of cars in upstate New York. As a birder, I’ve seen the sounds of guns scare off geese and ducks I was trying to observe in New Jersey waters, and shuddered over the skins of Northern Pintails and American Wigeons seen in boats along Alligator Alley, Florida. So–not a fan of hunting. And, neither are most of our 10,000 Birds writers. Just to make sure I was not being too personal in my reaction, I asked several birding friends their opinions. Reactions varied from confusion to distaste. Perhaps the most positive reaction came from noted bird photographer Marie Read, who noted that the information about waterfowl reaction to humans and decoys would be of great interest to nature photographers.

I had a long conversation with Richard Crossley at his request, and most of it focused on the hunting section. (We also discussed the overall educational goals of the guide, how the Crossley ID Guide series differs from traditional field guides, and how British birding differs from U.S. birding. I informed Crossley before the conversation that it would inform my review, but would not influence it.) I initially assumed that hunting information was included to widen the scope of the book’s audience and increase sales. Crossley, however, articulated a different goal.

He strongly believes that waterfowl hunters are the major reason we have waterfowl and wetlands in North America today. “The numbers don’t lie,” he told me. And, let’s face it, he is right. As of January 2017, Ducks Unlimited has conserved 13,902,792 acres in North America, including 5,509,855 in the United States.* And, proceeds from sales of Duck Stamps have secured and protected over 6 million acres of wetland and grassland habitat.** (Though, Duck Stamp sales are decreasing, a major cause for concern.) Crossley writes in his Introduction, “Hunting waterfowl for food and sport is a long-standing tradition in North America, with its roots tracing back at least 2,000 years to Native Americans who used Canvasback decoys. Today there are an estimated 1.2 million to 2.2 million waterfowl hunters in the U.S. and Canada.” If we are to continue preserving our wetlands, birders need to recognize their common bond with hunters and engage in conservation as vigorously as they do. This identification guide is not a book for birders with hunters tacked on as a secondary audience; it is an identification guide for birders and hunters. Because, increased knowledge of waterfowl will lead to increased, even passionate interest in conservation.

The case for considering hunters as allies in wetlands conservation is an underlying theme of the extremely informative chapter on “Saving Waterfowl and Wetlands,” written by co-author Paul Baicich, that ends the book. Baicich takes us through the history of wetlands and waterfowl conservation policy, planning, and legislation (much, but not all seemingly motivated by the desire to conserve enough habitat so that waterfowl hunters will have a wealth of targets) and offers nine recommendations for what we can do. The top three are: buy Duck Stamps, support the Jr. Duck Stamp program, and join wetlands conservancy organizations like Ducks Unlimited, Ducks Unlimited Canada, Delta Waterfowl, and The Nature Conservancy. (Further down the list is the spirited suggestion to build duck nest boxes, followed up with detailed instructions on how to build nest boxes for specific species.)

Still, hunting in a bird identification guide? It is not totally without precedent. Richard LeMaster’s spiral-bound Waterfowl Identification: The LeMaster Method (Stackpole Books, 1996) was written for hunters and used by birders. But, that guide focused on duck’s bills, not on hunting strategies. I’m withholding judgment for the time being. And, I am very interested in what you think. Let me know in the comments section.

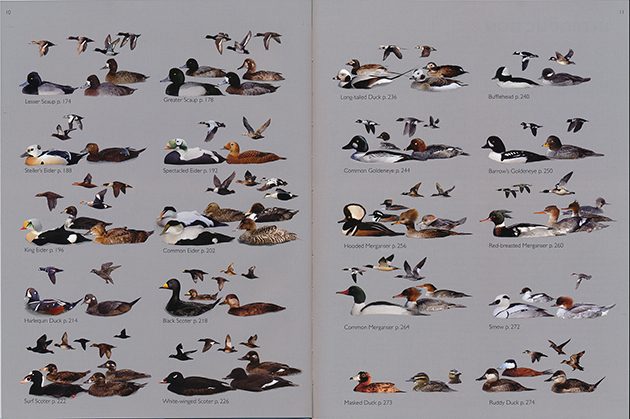

Access and Organization: There are multiple ways to find a specific waterfowl species: (1) a traditional Table of Contents, which directs the user to both the Visual and Written Species Accounts (plus other sections of the book, including Mystery Images); (2) a visual index, which utilizes bird images to direct the user to the first page of each species’ Visual Species Account (and, not just one image, as you can see in the pages above); an Index of scientific and common names, directing the user to both the Visual and Written Species Accounts, with page numbers to the color plates printed in bold. I was glad to see that names are arranged by genus followed by species; in other words, ‘American’ and ‘Eurasian’ are listed under ‘Wigeon,’ and americana and penelopeare listed under Mareca.

Species do not appear to be organized according to a specific taxonomy, though there is rhyme and reason to species order. Swans are treated first, followed by geese and then dabbling ducks, diving ducks, and, finally, exotics. Ducks are mostly grouped together by genus; Gadwall, American Wigeon, and Eurasian Wigeon, the Mareca species, follow each other, though Falcated Duck, the fourth Mareca species, is a bit further down, in a spread devoted to rarities.

Surprisingly for a guide that pays so much attention to access, it is not easy to switch back and forth from the Visual to the Written Species Accounts. Well, I should amend that; it is simple to go from the written to the visual–the plate page number is printed in bold at the top of the Written Species Account. But, if, let’s say, I want to go from the Redhead Visual Species Account to the Redhead Written Species Account, I need to check the Table of Contents or the Index, a two-step process. The page number is not printed here. I really don’t understand why, unless it is to avoid some of the pitfalls addressed in the next paragraph.

Other Considerations: There are a number of spelling and organizational errors in The Crossley ID Guide: Waterfowl. Astute readers may have noticed one above in the quote from the Introduction about rectrices, spelled incorrectly as “juvenile retrices.” (This quote wasn’t selected for this reason, I just happened to notice it as I was proofreading.) Several of the page references are incorrect. The plate on Mystery Brant, for example, refers the reader to page 234 for answers when it should be page 485. the plate on Rust-stained Birds does not give the answer page (487). And, in the chapter on “Saving Waterfowl and Wetlands,” a reference is given for a map on page 500; the map is located on page 502. All of these are relatively minor errors and, sadly, this is not unusual in reference publications I’ve reviewed lately. And, I probably wouldn’t even mention the issue except that as I was writing this review my eye focused on the photographic flight plate for “Red-breasted Maerganser.” A major spelling error that will have consequences for search if the guide is digitized. Hopefully, all errors will be corrected in future editions.

Photographs: There are so many images encased in the identification plates, over 5,000, and most of them are by Richard Crossley. About 40 (not including the wing images) are by other photographers, and it says something about the comprehensiveness of Crossley’s photographic achievement that most of these are of very specific birds–rarities or hybrids. The photographic plates are composed with an eye for technical elements–focus, clarity of detail, precise poses of the whole body sitting or in flight, unobscured by branch or shadow. And, in an effort to approximate ‘reality,’ their composition is often busy, sometimes messy. So, I offer the above plate of male King Eiders performing their courtship display. Crossley asks us to examine each image and the individual behavior. I suggest we enjoy the composition as a whole. The symmetry and beauty of this bird in its multiple images may not portray something we will ever see in real life, but it does reflect nature’s capacity for astonishing beauty.

Authors: Richard Crossley is known as co-author of The Shorebird Guide (with Michael O’Brien and Kevin T. Karlson, 2006, HMH), author of The Crossley ID Guide: Eastern Birds (2011, PUP), and co-author of The Crossley ID Guide: Britain and Ireland (with Dominic Couzens, 2013, PUP) and The Crossley ID Guide: Raptors (with Jerry Liguori and Brian L. Sullivan, 2013, PUP). He is also, with this volume, now a publisher and distributor (The Crossley ID Guide: Waterfowl is only available from Crossley Books as of this writing, the book includes a nifty for-use-in-the-field laminated waterfowl identification pamphlet). A Brit who has relocated to the States (specifically, Cape May, N.J.), Crossley has positioned himself as a birder, author, and photographer challenging the traditional ways of the U.S. birding world, and aggressively working to change how we learn about and identify birds.

He has wisely chosen his co-authors, Paul Baicich and Jessie Barry. According to the Preface, Baicich and Barry wrote most of the written Species Accounts. Baicich also wrote the chapter at the end of the book, “Saving Waterfowl & Wetlands.” Crossley himself wrote “most” of the Introduction and is responsible for the visual Species Accounts and text.

Jessie Barry has worked for the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology since 2008, most recently as Program Manager, Macaulay Library and Merlin Project Leader. Barry has written for birding magazines and been involved in young birder programs, but her greatest achievement, in my humble opinion, is that she is a member of Team Sapsucker, the Lab of O birding team that engages in Global Big Day fundraising events. (She also grew up in upstate New York, which makes me wonder if she had a hand in that Buffalo mystery bird page?)

Paul Baicich has spent a lifetime working for birding and wildlife organizations, writing about birds and conservation, and advocating for aggressive conservation programs by the government, nonprofits, and individuals. He was also an active active member and local leader in the Machinists Union (IAMAW) for 15 years, a fact I found out from his latest article in The Nation, Baicich’s past books include Feeding Wild Birds in America: Culture, Commerce, and Conservation (co-authored with Margaret A. Barker and Carrol L. Henderson, 2015, Texas A&M University Press) and Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds: Second Edition (co-authored with Colin J. O. Harrison, 2005, PUP). A vocal supporter of the Duck Stamp program, Baicich is president of the Friends of the Migratory Bird/Duck Stamp, and in 2014 received the Ducks Unlimited “Wetland Conservation Achievement Award,” Communications category.

Conclusion: The Crossley ID Guide: Waterfowl is an identification guide that fills a surprising niche. Despite waterfowl’s popularity with nature lovers, there has up to now been no comprehensive guide to the swans, geese, and ducks of North America. The closest contenders are Chris Early’s Waterfowl of Eastern North America, Firefly Books, 2005 and Waterfowl of North America, Europe, and Asia: An Identification Guide by Sébastien Reeber, PUP, 2016. Waterfowl can be found everywhere and anywhere in North America, but I think this guide will be particularly useful to birders (and hunters) on the coasts, near the Great Lakes, and along the mid-continent flyways. And, I think that it can be used easily and intelligently by birders of all levels. Advanced birders are likely to be particularly engaged by the material on molt and subspecies. It’s hard to believe that there are any birders or naturalists or hunters who will not appreciate the amazing photographic plates, but I believe that they have a special appeal for younger birders, who have grown up in a world where learning is visually-based.

It is important to remember that The Crossley ID Guide: Waterfowl is not a field guide; it is a reference source that aims to educate, provide a framework of knowledge within which to work out id’s. The extended textual material contains information comparable to that found in of the authoritative online Cornell Lab of Ornithology guide Birds of North America (minus the scientific citations). The photographic plates show poses and plumages and perspectives not seen in the typical field guide. Quizzes and questions within the text challenge and engage the user in an ongoing educational process. Happily, the ID Guide can also be used for short-term answers–to separate out the Lesser Scaup from Greater, to pick out the Ross’s Goose from the flock of Snow Geese, to examine that photo you took of ducks taking off from the bay and identify every single merganser and goldeneye. These are identification puzzles that are addressed in other guides and handbooks, but not as comprehensively and not all in one book.

This is an expensive book–$40 plus tax and shipping and no Amazon discount because it is only available from the eponymous publisher. Smartly, it has been published at a time of need–duck and goose season is upon us!–and just before the giving holidays. If you are passionate about ducks, geese, and swans, seriously consider putting The Crossley ID Guide: Waterfowl on your wanted list. I think you’ll find it’s worth the investment.

—–

*Ducks Unlimited National Fact Sheet, http://www.ducks.org/media/_global/_documents/stateFactSheets/NationalFactSheet.pdf.

** American Birding Association, http://aba.org/stamp/

The Crossley ID Guide: Waterfowl

by Richard Crossley, Paul Baicich, & Jessie Barry

Crossley Books, 2017

flexibound, 512pp., 16 x 10 x 6 inches

ISBN-10: 0692900357; ISBN-13: 978-0692900352

$40.00; available only from Crossley Books (as of date of this review)

Very excellent review of what seems like a comprehensive waterfowl field guide. Hunting is a sensitive subject and will draw many emotional opinions. In the “North American Conservation Model,” hunters did supply needed revenues for wetlands conservation historically. And primal peoples–those perceived as closer to nature–have hunted since the dawn of modern homo sapiens. Aldo Leopold, the father of the “land ethic” and game management, was a prolific hunter. Thankfully, revenue support is increasing from non-consumptive recreationists. A hunter once told me that he never kills what he would not eat. That to me is what hunting is. As a sport, especially in ill-conceived “wildlife refuges,” it is nauseating and criminal. The paradox is highlighted by the work and close friendship of John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt. It will not go away, so I accept it in this otherwise excellent book.

Thoughtful comments, Jeffrey. Thanks.

Although this is too heavy (for me) to carry in the field, this is my favorite ‘go to’ guide for when I get back to my car or the hotel and try to identify the more ‘difficult’ birds–especially from photos that I’ve taken. I like how the images are modified slightly to show the birds more as they would actually appear in the field and pictured against backdrops of the habitats you would expect to see them in. I prefer these over photos and traditional drawings.